Getting the most out of each workout requires more than just following a great training

program. Consistent performance also requires an optimal balance between

training and recovery. Mention the subject to most clients, though, and you’re

likely to meet with disinterest or even resistance. Clients rarely think of

recovery as a planned activity, and others go so far as to believe that time

spent recovering will interfere with goal achievement.

So, in addition to all of our other roles as exercise experts, it’s up to us to help clients learn how and why to embrace recovery. Make sure recovery training is on your and your clients’ radar with this research review of its substantial benefits and the proper strategies for optimal recovery. Further, you’ll find a practical overview of how a recovery program can be integrated into the NASM Optimum Performance Training™ model.

Defining Recovery

Recovery relies on a reduction of, change in or break from stressors (Kellmann & Beckmann 2018). A more comprehensive definition of recovery is “an inter- and intraindividual multilevel (e.g., psychological, physiological, social) process in time for the re-establishment of personal resources and their full functional capacity” (Kallus & Kellmann 2016).

Exercise and training lead to tissue damage, inflammation, soreness and perceived fatigue (Dupuy et al. 2018). Kellmann et al. (2018) refer to this as “functional overreaching,” adding that it is required for performance enhancement but “can be compensated through comprehensive recovery.” These researchers go on to say that if recovery is not achieved, the athlete moves into a state of underrecovery, which serves as a precursor to overtraining syndrome.

Avoiding underrecovery begins by applying recovery strategies

systematically. Recovery strategies can be those activities that take place

either following a training session or between training sessions. Kellmann and

colleagues define such activities—whether passive (e.g., massage) or active

(e.g., postexercise cooldown)—as regeneration (Kellman et

al. 2018). Other recovery categories include sleep, nutrition and alleviation

of nervous system fatigue, as well as effective stress management skills, as it

is the culmination

of events that ultimately determine the body’s state of readiness.

Passive recovery techniques—such as massage, cryotherapy, compressive garments, water immersion and electrostimulation—are garnering a significant amount of evidence supporting their use as effective methods of recovery (Dupuy et al. 2018). As these strategies require either a license or expensive equipment, I won’t cover them here.

**Follow the link for a blog post and a great overview of passive recovery strategies.

Instead, I will focus on active recovery strategies—those that require the user to be an active participant—are the focus of this article.

Measuring Recovery

In research studies, the most common measures of recovery are markers of

performance (e.g., strength, power, speed) and soreness after a workout

(referred to as delayed-onset muscle soreness, or DOMS). A recovery method is

considered effective if it results in the user experiencing less soreness and

recovering baseline levels of strength and power more quickly.

It is important to recognize that while recovery techniques vary, they

share a similar purpose: facilitating the removal of metabolic waste (e.g.,

damaged proteins) from the muscle and allowing fresh nutrients to infiltrate

the area (Dupuy et al. 2018).

I would be remiss if I did not at least mention that lactic acid or

lactate production is likely not associated with muscle fatigue or

soreness and does not need to be “removed” or “flushed out.” As Len Kravitz,

PhD, points out, the burning sensation during exercises (i.e., acidosis) is a

result of the accumulation of protons in the cell. Lactate is produced in

response to this proton accumulation to help “neutralize or buffer the cell”

(Kravitz 2005). Therefore, lactate production is, in fact, a positive response

to intense exercise.

Active Recovery Strategies: Research and

Timing

Active regeneration strategies may be integrated immediately after a

training or exercise session (cooldown, stretching and myofascial rolling), or

they may be performed between sessions (low-intensity exercise). Let’s look at

when each strategy is intended to be performed, why the timing matters and what

support research offers.

Cardio

Cooldown (Immediately After)

While the common cooldown of 5–10 minutes of cardio post-exercise is

still one of the most popular methods of active recovery, there is little

evidence that it is superior to other types of recovery. In one study, Coffey,

Leveritt & Gill (2004) found that a traditional cooldown was the same as a

passive recovery after intense exercise. Similarly, when a 20-minute cycling

bout was performed at a moderate intensity (~70% of heart rate maximum) after

eccentric knee extensions (which induced DOMS), participants felt the same

level of discomfort as those in the low-intensity group (~30% of HRmax) (Tufano

et al. 2012). The researchers noted a reduction in DOMS in both groups at the

72- and 96-hour marks, which was likely due to natural causes and nothing to do

with the aerobic exercise.

The traditional cardio cooldown may provide the body with a smooth

transition from an exercise state back to a steady state, but the research does

not fully support a bout of light- or moderate-intensity aerobic exercise to

reduce the negative effects of DOMS. Therefore, it is not wrong to include

cardio as part of a cooldown, but know this may not be the key to

reducing DOMS.

Static

Stretching (Immediately After)

Stretching has been used to help prevent muscle imbalances by restoring

optimal muscle length. It is frequently touted as a way to prevent or reduce

the negative effects of DOMS. The research to support this notion is scarce.

However, stretching combined with other recovery strategies has proven to be

effective. Calleja-González et al. (2016) stated that massage combined with

stretching produced a positive effect on recovery when applied immediately

after a sports competition. But how can these results be replicated if an

individual cannot get a massage after each training session? Let’s explore the

use of myofascial rolling with the thought of it being a viable substitution.

Myofascial

Rolling (Immediately After)

The research on myofascial rolling has increased significantly over the

past 5 years. Such research has found that using roller massage as part of an

active recovery may help to speed up the recovery process (MacDonald et al.

2014; Wiewelhove et al. 2019). In a recent meta-analysis, Wiewelhove and

colleagues reviewed seven studies that explored the effects of post-exercise myofascial

rolling, and the researchers found that it reduced the perception of pain

caused by DOMS and, albeit slightly, helped to restore sprint and strength

performance. However, there is currently no evidence-based rationale for why

those who use roller massage experience a reduction in discomfort.

Hotfiel et al. (2019) highlighted that swelling via an accumulation of

interstitial fluid, as well as the presence of inflammatory substances, was

likely to blame for the pain with DOMS. It is reasonable to assume that the

direct compression and rolling help to move and potentially recirculate the

accumulated fluid, thus reducing the perception of pain. Further elaborating

this idea of post-exercise compression and DOMS, Beliard et al. (2015) and

Dupuy and colleagues explored compression garments used after exercise and

found that DOMS did indeed decrease.

Whether the positive results are due to flushing of inflammatory fluids

and metabolic waste or something else, such as a neurophysiological effect

occurring via a nervous system response, there appears to be support for using

roller massage as part of an integrated recovery strategy. It is important to

recognize that the use of myofascial rolling does not eliminate soreness but

may significantly reduce it. Therefore, returning to the question posed in the

section on stretching, it is possible that combining post-exercise myofascial

rolling with stretching may result in recovery benefits similar to those found

with massage plus stretching.

Low-Intensity

Exercise (Between Sessions)

In one thorough review, Cheung, Hume & Maxwell (2003) concluded that

low-intensity exercise was the most effective method of reducing soreness

between exercise sessions. It is important to recognize that such exercise is most

beneficial after

soreness is already present. Cheung, Hume & Maxwell included

that the individual should perform familiar total-body movements for 1–2 days

after the DOMS-inducing exercise.

It is speculated that the rhythmic contraction of muscles during

exercise may serve as an effective “pump” to mobilize inflammatory fluids that

are often associated with DOMS or to “warm up” the tissue, which may have a

temporary pain-reducing effect. However, there is far more evidence to suggest

that movement produces a pain reduction effect through complex cortical

processes. A study from the University of Iowa cites numerous studies that

demonstrate that exercise can reduce pain in people with knee replacements,

osteoarthritis and other chronic pain syndromes. It appears that exercise helps

to manage the central nervous system by inhibiting many of the pain-producing

mechanisms and reducing excitation (Lima, Abner & Sluka 2017).

The exercise used in such research is generally traditional aerobic

exercise, such as the use of a stationary bike or treadmill; however, this is

due to the ease of controlling the intensity and availability of such

equipment. Calisthenics—defined by Tsourlou et al. (2003) as exercises that

solely use one’s body weight—can help to significantly reduce pain in

conjunction with traditional therapy (Gurudut, Welling & Naik 2018).

Recovery Training With the NASM OPT™

Model

To summarize, the research points to the use of (1) myofascial rolling

and light stretching immediately after training, and (2) low-intensity,

total-body movement sessions between higher-intensity sessions.

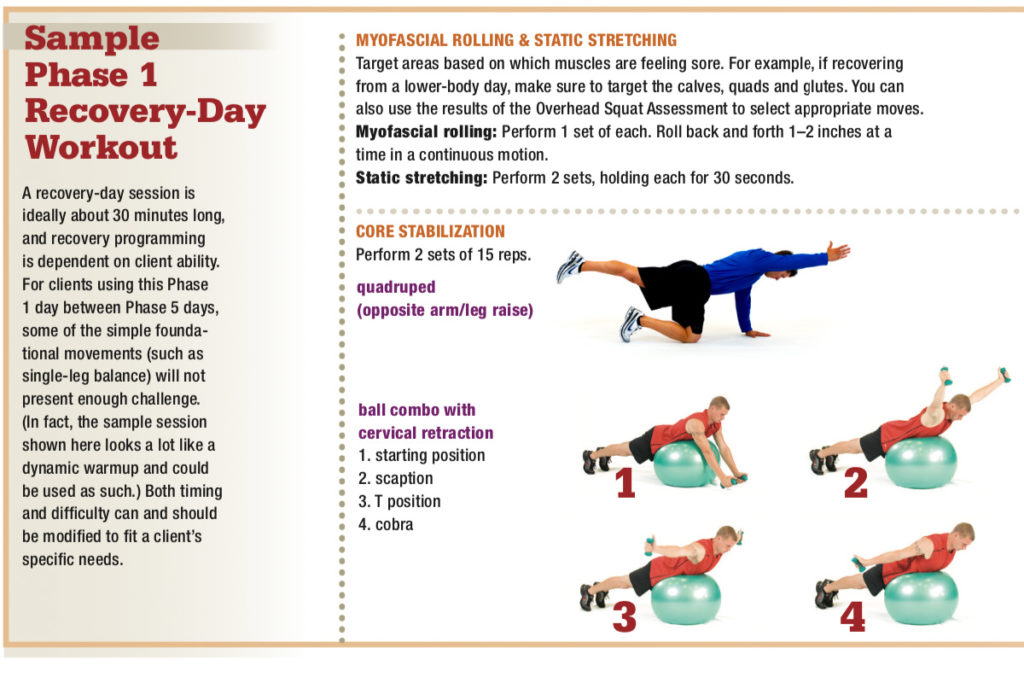

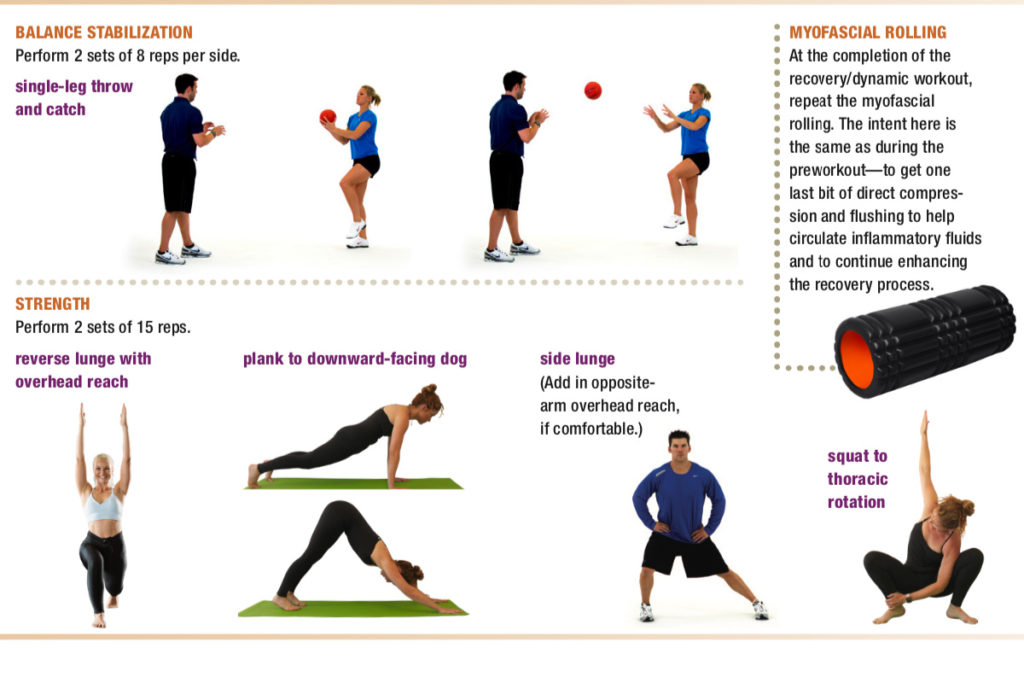

Using the NASM OPT model as a framework, a “recovery day” could include

a Phase 1: Stabilization Endurance workout planned 1–2 days after a Phase 3, 4

or 5 workout. This Phase 1 workout should be implemented according to NASM with

these exceptions:

SMR: When myofascial rolling, do not hold on tender spots.

Think of the rolling application as being a method of “flushing” the tissue. Roll back and forth in slow, continuous motion (1–2 inches per second for 30–60 seconds). Reserve the tactic of “holding pressure on one spot” for your pre-exercise rolling routine.

Plyometric and SAQ training: Avoid these.

Plyo and speed, agility and quickness (SAQ) exercises should be avoided due to the impact and the high levels of eccentric deceleration involved, which can exacerbate the discomfort associated with DOMS.

Body-weight moves: Emphasize mobility-enhancing exercises.

For example, instead of a regular lunge, add in an overhead reach (see “Sample Phase 1 Recovery-Day Workout,” below). These total-body mobility moves will do more than just encourage flexibility, as integrating more moving parts encourages a higher heart rate and an increase in overall tissue temperature.

Resistance moves: Modify the tempo.

More specifically, do not emphasize the eccentric phase of the exercise—have the client use smooth, coordinated and continuous movements. I know this sounds blasphemous to many hardcore NASM-ers, but the rhythmic contractions are helping to move fluid and metabolic waste through the sore tissues.

Reading Up on Recovery

Recovery and regeneration are hot topics for athletes and the general population, as well as for researchers. With the growing research and recovery technology, I encourage you to do a personal exploration of the field to determine what works best for your environment and with your clients. Learning as much as you can about recovery will allow you to provide more comprehensive service to every client. Being able to plan recovery sessions instead of merely recommending recovery will get your clients to their goals sooner and boost your business!

Specialize in Corrective Exercise

As a certified personal trainer, it’s important to realize that just about every client you work with may be susceptible to common injuries and ailments, ranging from lower-back pain to anterior cruciate ligament tears to shoulder pain. NASM’s Corrective Exercise Specialization applies to all clients, which means it lets you bring increased value to new and existing customers. Obtaining the NASM-CES demonstrates your continued passion and investment in education. Establish yourself as a fitness industry leader today.

[easy_media_download url="https://blog.nasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/AFM_Fall19_SM.pdf" text="Download the Fall 2019 Issue of the American Fitness Magazine" width="550" color="blue_four" target="_blank"]