Recovery is the return to a normal state of health, mind, or strength.

Optimal recovery is best attained through an integrative approach, focusing on nutrition, sleep, and stress management.

Nutrition to Enhance Recovery

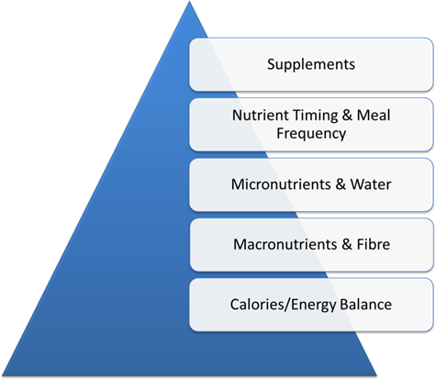

Nutrition to enhance the recovery process should be prioritized as follows:

1. Energy balance/availability

2. Macronutrients

3. Micronutrients

4. Hydration

5. Nutrient timing

6. Supplements

ENERGY BALANCE & AVAILABILITY

Energy (calories) is the foundation of the repair process. Optimize your energy by focusing on the 3 Ts:

1. Total- Match your caloric intake with your training/activity requirements and goals.

2. Type- Focus on carbohydrates for energy and glycogen restoration, adequate-protein for repair and muscle protein synthesis, and healthy fats to minimize inflammation and support overall health.

3. Timing- Time your meals strategically around training sessions and competitions.

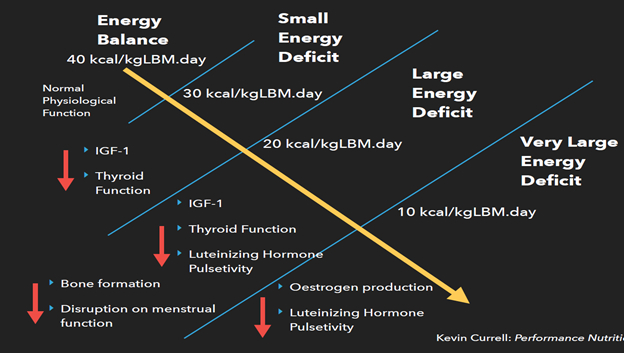

Energy availability (EA) is the difference between energy intake (diet) and energy expenditure (exercise, training and competing, and NEAT- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis). It is essential for health, performance, and recovery.

Low Energy Availability (LEA) occurs when there is an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure, resulting in an energy deficit.

LEA can be unintentional, intentional, or psychopathological (e.g., disordered eating). It is a factor that can adversely impact reproductive, skeletal, and immune health, training, performance, and recovery, as well as a risk factor for both macro-and micronutrient deficiencies.

Energy Availability Formula

Energy availability = (Energy intake (kJ) − Energy expenditure during exercise (kJ))/fat-free mass (kg)

(Ong, J. L., & Brownlee, I. A., 2017)

MACRONUTRIENTS

CARBOHYDRATES

Carbohydrates (CHO) are the primary energy source for moderate-intense activity. A general carbohydrate guideline is to match needs with activity:

● Low intensity/skill-based: 3–5 g/kg BW

● Moderate intensity: 5–7 g/kg BW

● High intensity: 6–10 g/kg BW

● Extreme: 8–12 g/kg BW

Carbohydrates and Recovery

During post-exercise recovery, optimal nutritional intake is essential to replenish endogenous substrate stores and facilitate muscle-damage repair and reconditioning. After exhaustive endurance-type exercise, muscle glycogen repletion forms the most critical factor determining the time needed to recover.

The postexercise carbohydrate (CHO) recommendations are 1 g/kg/ BW hour for four hours, then match activity needs (see above). This is the most critical determinant of muscle glycogen synthesis.

Since it is not always feasible to ingest such large amounts of CHO, the combined ingestion of a small amount of protein (0.2−0.4 g · kg−1 · hr−1) with less CHO (0.8 g · kg−1 · hr−1) stimulates endogenous insulin release. It results in similar muscle glycogen-repletion rates as the ingestion of 1.2 g · kg−1 · hr−1CHO.

Consuming CHO and protein (4:1) during the early phases of recovery has been shown to affect subsequent exercise performance positively and could be of specific benefit for athletes involved in numerous training or competition sessions on the same or consecutive days. (Burke, L. M. 2015) (Smith-Ryan, A., & Antonio, J. 2013) (Beelen, M. et al. 2010)

Carbohydrate dosing relative to resistance training should be commensurate with the intensity guidelines outlined above.

Read also: Are Carbs Really That Bad for You?

PROTEIN for Recovery

Optimum protein consumption is key to stimulating muscle protein synthesis and facilitating repair. Protein recovery guidelines for strength training include:

● Protein Dose: 1.6–2.0 g/kg BW

● 0.25–0.5 g/kg BW/meal in 4 divided meals

● Branch Chain Amino Acids- Leucine dose: 3 g is optimal to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (whey is a good source)

● The addition of 50 g of carbohydrate with protein pre and post-exercise can decrease muscle breakdown

● Consuming 1–2 small protein-rich meals in the first 3 hours post-exercise can capture the peak of muscle protein synthesis

(Dreyer, H. C., Drummond, et al. 2008) (Norton, L. E., & Layman, D. K. 2006) (Smith-Ryan, A., & Antonio, J. 2013) (Naderi, A. et al. 2016)

You might be interested: Recipes for Gaining Muscle

FAT

During the recovery process, fats are important as an energy source, hormone production, and inflammation reduction.

Essential Fatty Acid Balance

The Standard American Diet (SAD) is notoriously pro-inflammatory, with the Omega 6:Omega 3 greater than 4:1 (closer to 18:1).

To reduce inflammation and enhance recovery, athletes should focus on getting the fats in their diet from dark green leafy vegetables, flax/hemp seeds, walnuts, cold-water fish, grass-fed beef, omega-3 eggs; and limit omega-6 (vegetable and seed oils). Saturated fat should come from grass-fed, pasture-raised animals. Olive and avocado oils are good choices for cooking. (Simopoulos, A. P. 2008). Athletes should consume 20 to 35 percent of their calories from fat.

See how to track macros in this blog post.

MICRONUTRIENTS AND PHYTONUTRIENTS

Micronutrients include vitamins and minerals. They are required in small quantities to ensure normal metabolism, growth, and physical well-being.

If your diet is 50-75% plant-based and includes healthy fats and adequate protein, you are likely to get the vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients you need without having to rely on supplementation.

Phytonutrients, also called phytochemicals, are chemicals produced by plants. Phytonutrient-rich foods include colorful fruits and vegetables, legumes, nuts, tea, cocoa, whole grains, and many spices. Phytonutrients can aid in the recovery process due to their anti-inflammatory properties.

Antioxidants- Too much of a good thing?

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are free radicals that are produced during exercise that can cause skeletal muscle damage, fatigue, and impair recovery. However, ROS and RNS also signal cellular adaptation processes.

Many athletes attempt to combat the deleterious effects of ROS and RNS by ingesting antioxidant supplements (e.g., vitamins A, C, E and the minerals Se and Zn). Unfortunately, interfering with ROS/RNS signaling in skeletal muscle during acute exercise may blunt favorable adaptations and can attenuate endurance training-induced. ROS/RNS mediated enhancements in antioxidant capacity, mitochondrial biogenesis, cellular defense mechanisms, and insulin sensitivity.

In addition, antioxidant supplementation can have harmful effects on the response to overload stress and high-intensity training, thereby adversely affecting skeletal muscle remodeling following resistance and high-intensity exercise.

The bottom line is that physiological doses (from the diet) are beneficial, whereas supraphysiological doses (supplements) during exercise training may be detrimental to one's gains and recovery.

(Merry, T. L., and Ristow, M. 2016)

HYDRATION

Water regulates body temperature, lubricates joints, and transports nutrients. Signs of dehydration can include fatigue, muscle cramps, and dizziness. During the recovery phase, staying hydrated can help stimulate blood flow to the muscles, which can reduce muscle pain. In addition, hydration can help flush out toxins which can exacerbate muscle soreness.

Are You Dehydrated?

- Clear - Good hydration, overhydrated to mild dehydration

- Pale Yellow - Good hydration or mild dehydration

- Bright Yellow - Mild to moderate dehydration or possibly taking vitamin

- Orange/Amber - Moderate to severe dehydration

- Tea/Apple Juice - Colored Severe dehydration

Endurance Sports Considerations

● Early consumption of at least 150% of fluid lost with dilute sodium solution (</= 50 mmol/L, e.g., isotonic sports drink)

● Events greater than 90 minutes require pre-event hydration strategies 2–3 days prior (e.g., consume 400-600 mL of fluid every 2–3 hours containing Na 40–100 mmol/L)

● Aim to hydrate back to pre-race weight

Homemade Electrolyte Recovery Drink

● 1/2 cup fresh orange juice

● 1/4 cup fresh lemon juice

● 2 cups raw coconut water

● 2 tbsp organic raw honey

● 1/8 tsp Himalayan pink salt

Blend ingredients and chill.

See for more on hyrdation: Hydration: Through The Lens of Fitness

NUTRIENT TIMING FOR RECOVERY

Timing your nutrition for recovery should include ensuring pre-exercise meal(s) adequately fuel your activity and that you optimize your macronutrients, as mentioned above, to maintain glycogen stores and protein balance.

While there is some debate with respect to the post-exercise “optimum window,” one should consider that it is likely that glycogen replenishment and protein consumption soon after exercise or an event can help optimize adaptations and recovery and minimize adrenal stress and catabolism.

SUPPLEMENTS FOR RECOVERY

Supplements can help enhance repair, but only when the foundation (energy, macros, micros, hydration, and timing) is covered. Supplements can be categorized based on how they support (not block) inflammation as well as their role in muscle, tendon, and bone repair.

Inflammation:

Inflammation:

● Bromelain: Generally about 500 mg 3x/day away from food

● Curcumin: 500 mg 3x/day (find a product with piperidine)

● Fish oil: 2000 mg 3x/day

Muscle Repair:

● Adequate protein (see protein section)

● HMB (Beta-hydroxy-beta-methyl butyrate): 3g/day

● Fish Oil: 4000 mg/day

● Creatine Monohydrate: 5000 mg/day for five days (in divided doses), followed by 3000 mg/day

● Polyphenols (micronutrients from plant-based foods): Consume a variety of colorful fruits, vegetables, herbs, and spices. Tart cherry juice has been shown to aid in muscle repair and soreness.

Tendon Repair:

● Collagen or gelatin: 10g/day

● Whey Protein: 20-40 g/day (about 3-5 g Leucine)

● Nitrates: From food (e.g., beets and chard)- increases circulation

● Citrulline Malate: 6,000 – 8,000 mg/day- increases circulation

Bone Repair:

● Adequate Protein and Carbohydrates

● Calcium: Aim for 1200 mg mostly from food sources

● Vitamin D: Per blood work (optimal levels are 40–60 ng/mL)

(Currell, Kevin., 2017) (Tipton, K. D., 2015)

Recovery smoothie (makes about two servings)

● 1 cup water

● 1 cup kale or spinach

● 1 peeled beet

● ½ cup frozen organic berries

● 1 banana

● ½ avocado

● ½ tsp raw cacao

● 30 g whey protein

● 2 tbsp ground flaxseed

Blend ingredients and enjoy!

Check out Athlete Recovery Techniques for more on supplementation

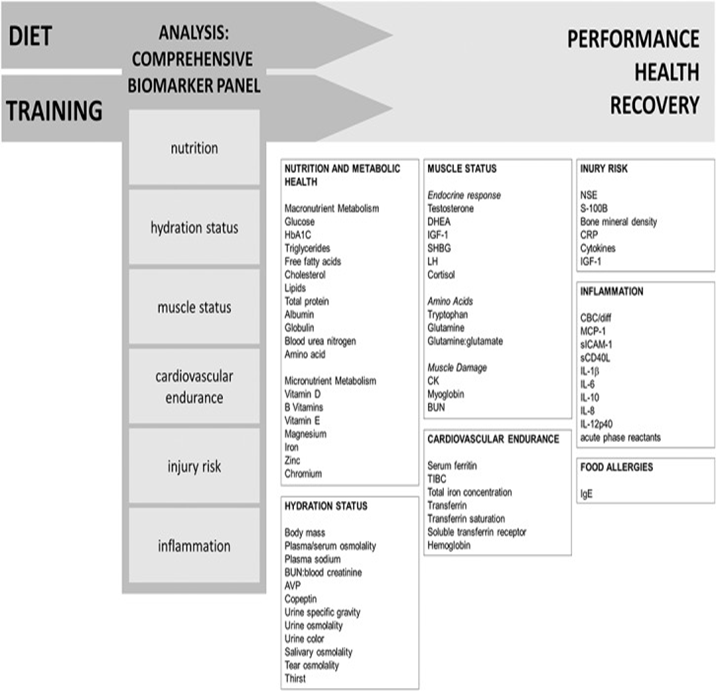

Monitoring Training and Recovery

There are several key performance biomarkers that can be used to monitor training and recovery. These include:

1. Nutrition and metabolic health

2. Hydration status

3. Muscle status

4. Endurance performance

5. Injury status and risk

6. Inflammation

Through comprehensive monitoring of physiologic changes, training cycles can be designed that elicit maximal improvements in performance while minimizing overtraining and injury risk.

Keep these in mind when you are doing active recovery work.

References

Beelen, M., Burke, L. M., Gibala, M. J., & Van Loon, L. J. (2010). Nutritional strategies to promote postexercise recovery. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 20(6), 515-532.

Bubbs, M. (2019). PEAK: The new science of athletic performance that is revolutionizing sports. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Burke, L. M. (2015). Re-Examining High-Fat Diets for Sports Performance: Did We Call the “Nail in the Coffin” Too Soon? Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.z.), 45(Suppl 1), 33–49. http://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0393-9.

Clark, M. A., Lucett, S., & Corn, R. J. (2008). NASM essentials of personal fitness training. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Currell, Kevin. Performance Nutrition. Crowood Press (April 1, 2017).

Dreyer, H. C., Drummond, M. J., Pennings, B., Fujita, S., Glynn, E. L., Chinkes, D. L., ... & Rasmussen, B. B. (2008). Leucine-enriched essential amino acid and carbohydrate ingestion following resistance exercise enhances mTOR signaling and protein synthesis in human muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism, 294(2), E392-E400.

Dupuy, O., Douzi, W., Theurot, D., Bosquet, L., & Dugué, B. (2018). An Evidence-Based Approach for Choosing Post-exercise Recovery Techniques to Reduce Markers of Muscle Damage, Soreness, Fatigue, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in physiology, 9, 403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00403.

Lee, E. C., Fragala, M. S., Kavouras, S. A., Queen, R. M., Pryor, J. L., & Casa, D. J. (2017). Biomarkers in sports and exercise: tracking health, performance, and recovery in athletes. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 31(10), 2920.

Malta, E.S., Dutra, Y.M., Broatch, J.R. et al. The Effects of Regular Cold-Water Immersion Use on Training-Induced Changes in Strength and Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 51, 161–174 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01362-0.

Melin, A. K., Heikura, I. A., Tenforde, A., & Mountjoy, M. (2019). Energy Availability in Athletics: Health, Performance, and Physique, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 29(2), 152-164. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/29/2/article-p152.xml.

Merry, T. L. and Ristow, M. (2016), Do antioxidant supplements interfere with skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise training?. J Physiol, 594: 5135–5147. doi:10.1113/JP270654.

Naderi, A., de Oliviera, E. P., Ziegenfuss, T. N., & Willems, M. E. (2016). Timing, optimal dose and intake duration of dietary supplements with evidence-based uses in sports nutrition. Journal of Exercise Nutrition & Biochemistry.

Norton, L. E., & Layman, D. K. (2006). Leucine regulates translation initiation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle after exercise. The Journal of nutrition, 136(2), 533S-537S.

Ong, J. L., & Brownlee, I. A. (2017). Energy Expenditure, Availability, and Dietary Intake Assessment in Competitive Female Dragon Boat Athletes. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 5(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports5020045.

Selye, H. (1950). Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. British medical journal, 1(4667), 1383.

Simopoulos, A. P. (2008). The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Experimental biology and medicine, 233(6), 674-688.

Simpson, N. S., Gibbs, E. L., & Matheson, G. O. (2017). Optimizing sleep to maximize performance: implications and recommendations for elite athletes. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 27(3), 266-274.

Smith-Ryan, A., & Antonio, J. (Eds.). (2013). Sports Nutrition & Performance Enhancing Supplements. Linus Learning.

Tipton, K. D. (2015). Nutritional support for exercise-induced injuries. Sports Medicine, 45(1), 93-104.

Venter, R. E. (2012). Role of sleep in performance and recovery of athletes: a review article. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 34(1), 167-184.

Young, H. A., & Benton, D. (2018). Heart-rate variability: a biomarker to study the influence of nutrition on physiological and psychological health?. Behavioural pharmacology, 29(2 and 3-Spec Issue), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0000000000000383.