Core stability and strength, while an important component of any person's fitness profile, is critical for the health and well-being of older adults. Conditions such as balance and coordination deficits, back pain, poor muscle endurance overall can be significantly improved if not alleviated by improving core strength in seniors.Likewise, optimizing the function of the core musculature can reduce the incidence of falls and allow seniors to complete activities of daily living independently- allowing them to remain functional and independent well into their older years (Granacher et al., 2013).

Want to train seniors? Consider becoming a personal trainer for seniors today!

What is the core?

The term "core" generally refers to the structures related to the human movement system in the trunk. If you recall your NASM-CPT course, the core is made up of the local stabilization system, global stabilization system, and movement systems.

The local stabilization system refers to the small type I "stabilizer" muscles that attach directly to the spinal cord. These muscle/muscle groups keep the spinal column stable and limit shock to the vertebrate. These muscles include the transverse abdominis (TVA), multifidi, pelvic floor, diaphragm, and internal obliques (Clark et al., 2018).

The global stabilization system refers to the muscles/muscle groups which attach the pelvis to the spine. These muscles provide stability between the spinal column and pelvis and allow for stability and control of the core while moving. These muscles/muscle groups include the adductors, gluteus medius, quadratus lumborum, external obliques, psoas major, rectus abdominis, and external/internal obliques (Clark et al., 2018).

Lastly, the movement system is composed of the muscles/muscle groups which connect the spine and pelvis to the extremities allowing for dynamic movement. These muscles include the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip flexor complex, and latissimus dorsi (Biel, 2010).

All muscles involved in the core must be functioning optimally without excessive shortening or lengthening at baseline. Equally, ideal muscle recruitment patterns are necessary to prevent injury and maximize movement capability in all people including older adults. Generally, older adults tend to have more sedentary lives which tend to promote suboptimal movement patterns and weakness in certain muscles in the core which makes core training critical in this population (McPhee et al., 2016).

Why is core training important for seniors?

As humans age, skeletal muscle tissue (in most people) is lost at a rate of 3 to 8 percent per year after the age of 30. The core is not excluded from this decline and atrophy of these critical muscles providing necessary spinal and pelvic stability as well as control over much of the human movement system can lead to significant disability and loss of independence over time (Volpi et al., 2004).

A well-rounded core training program, addressing each of these movement sub-systems, can significantly improve postural alignment, strength production, standing endurance, overall mobility, and decrease the risk of falls in elderly clients. Granacher et al (2013) conducted a randomized controlled trial to investigate the effects of a core training program on spinal mobility, trunk strength, balance, and functional mobility in a group of 32 seniors. The researchers found that these markers of a healthy core improved significantly in the group who engaged in the core training program.

Similarly, Ko et al (2014) not only found that a core training program improved markers of functional mobility but also found that markers of psychological well-being increased dramatically and the fear of falling decreased substantially. Overall, a balanced core training program can greatly increase the quality of life of seniors by improving endurance and mobility, while decreasing pain and fall risk as well as the risk of serious injury if a fall occurs (Ko et al., 2014).

What are good core exercises for seniors?

A well-designed core training program will address all parts of the movement sub-systems and rely on a client's specific movement pattern dysfunctions (do not forget to conduct your dynamic movement assessments). For instance, a client with an anterior pelvic tilt would not necessarily benefit from exercises that work the hip flexors (i.e., leg raises). Similarly, a client with a lordosis may not benefit from exercises that target the spinal extensors (i.e., back extensions).

However, a client with an anterior pelvic tilt could greatly benefit from exercises that strengthen the hip extensors (Likewise, it is important to assess your client's ability to get on and off the floor before selecting certain core exercises (Clark et al., 2018).

Many core training exercises appropriate for seniors will fall in the stabilization-endurance phase of the NASM OPT model, however, they can also be used in conjunction with strength-based training programs. Generally, these exercises should be completed at a low to moderate intensity with 12 to 20 repetitions and 1 to 3 sets of each exercise (Clark et al., 2018).

This is a list of a few common core exercises that can benefit seniors based on common movement pattern dysfunctions. It is critical to ensure proper assessment of your client to determine if any core training exercise is appropriate and beneficial to them.

Exercise #1: Quadrupeds

Purpose: Spinal stability, improved transverse abdominis activation.

Core muscles targeted: Transverse abdominis, gluteus maximus, erector spinae, rectus abdominus.

Training phase: Stabilization-endurance

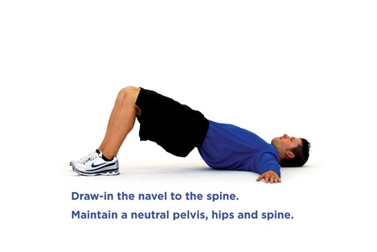

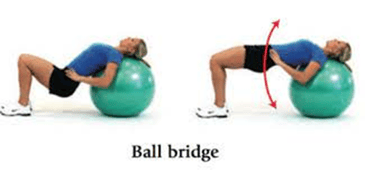

Exercise #2: Floor or ball bridge

Purpose: Improve hip extension range of motion and strength in the hip extensors.

Core muscles targeted: Gluteus medius and maximus.

Training phase: Stabilization-endurance.

Exercise #3: Half-kneeling or standing chops

Purpose: Improved coordination of anterior and posterior core muscles.

Core muscles targeted: Rectus abdominis, external obliques, internal obliques, transverse abdominis.

Training phase: Stabilization-endurance or strength-endurance (depending on progression).

Exercise #4: Pallof Press

Purpose: Improved control over trunk rotation.

Core muscles targeted: Rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis, internal and external obliques.

Training phase: Stabilization-endurance.

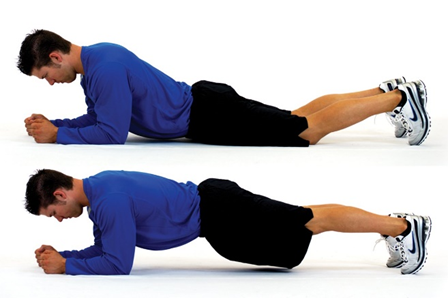

Exercise #5: Plank

Purpose: Improved stability and strength of the anterior trunk muscles; can improve posture and reduce back pain.

Core muscles targeted: Transverse abdominis, external obliques, internal obliques, multifidi.

Training phase: Stabilization-endurance

What are Some Safety Concerns for Seniors Working Out?

Older adults may present the certified personal trainer with additional considerations when it comes to assessment and program design. Adults over the age of 65 years have higher rates of arthritis, osteoporosis, metabolic disease (i.e., diabetes mellitus), peripheral artery disease, pulmonary disease, orthopedic considerations (disc herniation, spinal degeneration, joint problems), sarcopenia, and other conditions (Zaleski et al., 2016). Likewise, any medication usage should be noted as certain medications will affect training parameters. It is critical that seniors obtain medical clearance prior to beginning an exercise program.

Additionally, careful assessment is necessary before a trainer can design a program, including a core training program, for an older client. Older adults should be assessed by completing a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q), overhead squat assessment (OHSA) and basic postural assessment and possibly a balance assessment (i.e, Berg Balance Test) to screen for dysfunctional movement patterns, balance/coordination difficulties, proprioceptive deficits, and muscle weakness/atrophy (Golden, 2020).

The fitness professional must also decide if their client can safely get on and off the floor, and safely assume prone and supine positions. If this is not possible, alternate exercises must be selected based on the client’s individual needs.

Conclusion

Core training is a critical part of any exercise prescription, but particularly important for older adults. The fitness professional can ensure high quality program design by completing all recommended assessments for this population, paying special attention to the quality of movement patterns.

Ensuring your senior aged client has adequate core stability and strength can improve their overall quality of life tremendously by enhancing the client’s ability to coordinate movements, maintain spinal stability, prevent falls, alleviate the fear of falling, and helping them to remain functional and independent if possible.

References

Biel, A. (2010). Trail Guide to the Body. Books Of Discovery.

Clark, M. A., Lucett, S. C., Mcgill, E., Montel, I., Sutton, B., & Sports, O. (2018). NASM essentials of personal fitness training. Burlington Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Golden, N. (2020). Training Considerations for Older & Younger Populations. Blog.nasm.org. https://blog.nasm.org/training-older-and-younger-clients

Granacher, U., Gollhofer, A., Hortobágyi, T., Kressig, R. W., & Muehlbauer, T. (2013). The Importance of Trunk Muscle Strength for Balance, Functional Performance, and Fall Prevention in Seniors: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine, 43(7), 627–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0041-1

Granacher, U., Lacroix, A., Muehlbauer, T., Roettger, K., & Gollhofer, A. (2013). Effects of Core Instability Strength Training on Trunk Muscle Strength, Spinal Mobility, Dynamic Balance and Functional Mobility in Older Adults. Gerontology, 59(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343152

Ko, D.-S., Jung, D.-I., & Jeong, M.-A. (2014). Analysis of Core Stability Exercise Effect on the Physical and Psychological Function of Elderly Women Vulnerable to Falls during Obstacle Negotiation. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 26(11), 1697–1700. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.1697

McPhee, J. S., French, D. P., Jackson, D., Nazroo, J., Pendleton, N., & Degens, H. (2016). Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology, 17(3), 567–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0

Oliver, G. D., Dwelly, P. M., Sarantis, N. D., Helmer, R. A., & Bonacci, J. A. (2010). Muscle Activation of Different Core Exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(11), 3069–3074. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181d321da

Volpi, E., Nazemi, R., & Fujita, S. (2004). Muscle tissue changes with aging. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 7(4), 405–410. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2804956/#:~:text=Muscle%20mass%20decreases%20approximately%203

Zaleski, A. L., Taylor, B. A., Panza, G. A., Wu, Y., Pescatello, L. S., Thompson, P. D., & Fernandez, A. B. (2016). Coming of Age: Considerations In the Prescription of Exercise For Older Adults. Methodist

DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal, 12(2), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-12-2-98