As a CPT, in order to develop a solid program for clients, you must first take them through a complete assessment battery. The information you collect from initial consulations, flexibility, strength, performance, postural and cardiovascular testing of clients will help you to identify their deficits and set a baseline to build their program from. One of these groups of assessments is dynamic movement assessments.

What is the overhead squat assessment?

The overhead squat is a dynamic movement assessment. It is the quickest way to gain an overall impression of a client’s functional status. This assessment helps to evaluate one’s dynamic flexibility, core strength, balance, and overall neuromuscular control. As a person’s posture changes with every activity they perform in life, it is important that we evaluate the ability to handle the stresses placed on the kinetic chain. The overhead squat assessment is a tool that can assist with this.

The overhead squat assessment should be performed following a static postural assessment. The findings from the assessment should, therefore, further reinforce the observations made during the static postural assessment. In addition, faulty movements not revealed during the static postural assessment should be noted during the dynamic postural observations.

As noted before, the overhead squat assessment is designed to assess dynamic flexibility, core strength, balance, and overall neuromuscular control. It has been shown to reflect lower extremity movement patterns during jump-landing tasks (Buckley, Thigpen, Joyce, Bohres, & Padua, 2007).

Knee valgus during the overhead squat test is influenced by decreased hip abductor and hip external rotation strength, increased hip adductor activity, and restricted ankle dorsiflexion (Ireland et al., 2003; Bell & Padua, 2007; Vesci et al., 2007).

Decreasing the risk of injury through assessment

Movement impairments observed during this transitional movement assessment may be the result of alterations in available joint motion, muscle activation, and overall neuromuscular control, which some hypothesize increases the risk of injury. For example, research has indicated that individuals who possess increased knee valgus are at greater risk for knee injury (Ford et al., 2015; Hewett, Myer, Heidt, et al., 2005).

Being able to identify such compensations during the assessment allows the fitness professional to provide programming that can improve compensation and decrease the risk for knee injuries. The OSA is especially important when training older populations.

How do you perform the overhead squat assessment?

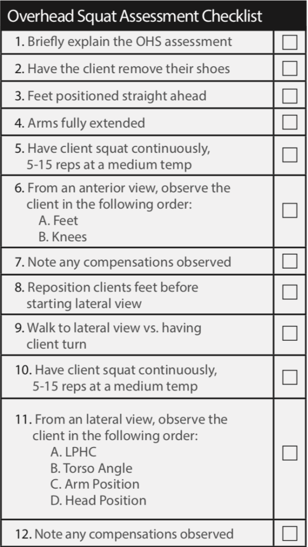

The general procedure for the overhead squat is:

Start Position

- The client should stand with hands overhead, and arms lined up with the ear.

- Eyes should be focused straight ahead on an object straight ahead.

- Feet should be pointed straight ahead, and the foot, ankle, and knee, and the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex (LPHC) should be in a neutral position with shoes off.

Movement

- Instruct the client to squat (at a natural pace) to roughly the height of a chair seat and return to the starting position.

- Repeat the movement for 5 repetitions, observing from each position (anterior and lateral).

As the fitness professional, it is important to obtain as much information as possible. This will require you to walk around a client and view them from different angles. Below are the major compensations you will want to look to observe.

Views

- View the feet, ankles, and knees from the front. The feet should remain straight, with the knees tracking in line with the foot (second and 3rd toes).

- View the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex (LPHC), shoulder, and cervical complex from the side. The tibia should remain in line with the torso while the arms also stay in line.

Compensations: Anterior View

- Feet: Do the feet flatten and/or turn out?

- Knees: Do the knees move inward (adduct and internally rotate)?

Compensations: Lateral View

- Lumbo-pelvic-hip complex:

- Does the low back arch?

- Does the torso lean forward excessively?

- Shoulder: Do the arms fall forward?

It is also important to know that other options exist to help you further determine what may be going on when observing potentially dysfunctional movement patterns. When performing the overhead squat assessment, a common compensation that can occur is an individual’s knees moving inward. This could be due to lack of range of motion at the ankle or weakness in the hips (or possibly both).

A way to further investigate the primary area of focus that may be causing this compensation is to have the individual place his or her heels on a 2×4 board or a pair of 10-pound plates, and then perform the assessment.

This places the foot/ankle complex in a plantar-flexed position, providing more dorsiflexion in the range of motion. If the knees stay more in line with the feet, then the foot/ankle complex may be the source of the issue. If the knees still move inward, then the source may be weakness of the hips.

A similar technique can be used when assessing the latissimus dorsi and its involvement when the low back arches. If the low back arches with the arms overhead, have the individual perform the squat with the hands on the hips.

If the low back does not arch with the hands on the hips, then latissimus dorsi extensibility may be the issue, as the latissimus dorsi is in the stretched position with the arms overhead. If the low back still arches with the hands on the hips, then core weakness may be the primary issue.

The fitness professional must be able to take in all of the information from various assessments, and assimilate it to build a picture of the current status of their client. Only then will a program be able to be developed to meet the client’s functional goals.

How do you interpret the overhead squat assessment?

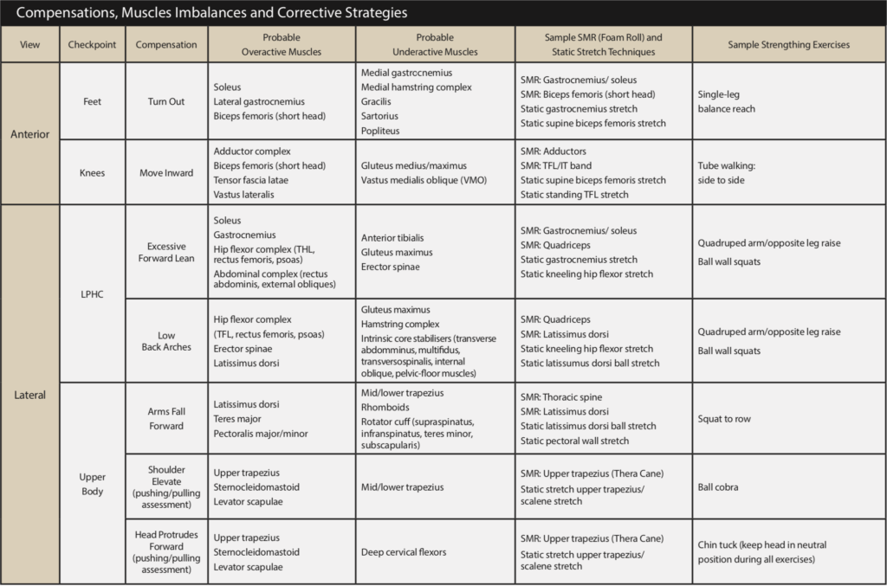

The most important part of the overhead squat assessment is the interpretation of the results. Without proper interpretation, it will become difficult to apply your findings in an effective manner for programming with your clients. The easiest way to interpret your findings is through the overhead squat solutions table.

This table will align your compensation findings with the probable overactive and underactive muscles leading to the movement discrepancies you are seeing. As a professional, there are a couple of major considerations you need to have.

The first is that the overhead squat assessment is not a diagnostic tool. This means that you will not be diagnosing specific issues or injuries. Rather you will let the body guide you to potential problems that you can help a client mitigate risks of. By addressing the potential problems the body is demonstrating, you will be able to see improved movement and hopefully a reduction in injury risk over time.

The second understanding you must have is the difference between overactive and underactive muscles.

Overactive, or shortened, muscles are those muscles that are commonly referred to as “tight”. This leads to a reduced range of motion at certain joints.

Underactive muscles are those that tend to have a decreased neural drive. In other words, they are not being activated for any number of reasons, leading to a lack of tension through them.

Both extremes are problematic, and our goal as fitness professionals is to address these potential issues through programming.

How do you apply it?

Once you have been able to interpret your findings, the final step is the application. There are many creative ways you can apply the overhead squat for maximum effect. The most important thing you must understand for the application is that you lengthen overactive muscles and activate underactive muscles.

This is a staple for corrective exercise professionals.

This means that you need to find ways to increase the ability of overactive muscles to stretch. This is typically done through a combination of foam rolling and static stretching. You must therefore find ways to activate underactive muscles by programming resistance exercises for these muscles.

This approach does not suggest that you ignore all other muscles and focus solely on the ones as identified through the assessment. Rather, you should develop a targeted plan that has a portion of each workout devoted to the lengthening of overactive muscles and activation of underactive muscles. This will become known as your corrective exercise strategy and can be employed as part of your client’s homework.

The improvement in movement as demonstrated through continued evaluation with the overhead squat assessment should become a routine part of any goal setting strategy for all of your clients. This will become one more way that you are not only able to show your client improvement, but it will help guide you in the development of a long-term program that will lead your client to success!