Maintaining a strong pelvic floor is vital during pregnancy, yet it remains a commonly overlooked and misunderstood component of most pre- and postnatal training programs. (It’s also something many of us shy away from talking about.)

If you train pre-and-postnatal clients, or you are a fitness specialist training women, the pelvic floor deserves your attention!

A strong pelvic floor is essential for preventing incontinence and other serious problems like pelvic pain, organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction. Stress incontinence (urine leakage from increased pressure during coughing, sneezing, running, jumping, etc.) is common during pregnancy and postpartum because of the relaxin hormone that softens ligaments and added gestational weight which increases the pressure on the pelvic floor. Women who begin pregnancy overweight or obese are more likely to experience pelvic floor problems as well as those who have children later in life. Some of the other risk factors associated with pelvic floor dysfunction include smoking, high hip circumference, depression, recurrent UTI, and interventions during labor (Durnea, Constantin M. et al., 2017). The pelvic floor issues that begin before or during pregnancy will likely continue postpartum and become more severe if not adequately addressed. In addition to mental and physical distress, pelvic floor problems can derail a woman’s exercise program. Fortunately, there are proven ways that trainers can help their clients minimize symptoms and help prevent them from progressing into severe long-term ailments.

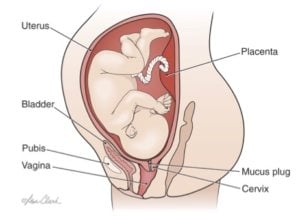

3rd Trimester Prenatal Anatomy © All Rights Reserved, Lisa Clark, Medical Illustrator, MA, CMI. clark-illustration.com

3rd Trimester Prenatal Anatomy © All Rights Reserved, Lisa Clark, Medical Illustrator, MA, CMI. clark-illustration.com

Incorporating pelvic floor exercises and body awareness in women’s training programs is crucial. Performing Kegels throughout pregnancy and soon after the baby is born is the easiest and most effective way to prevent pelvic floor dysfunction (Neels et al., 2017). The Kegel exercise, named after Dr. Kegel who created the pelvic floor muscle training method, is the repeated contracting and relaxing of pelvic muscles. To perform the exercise, squeeze the pelvic floor as if attempting to stop the flow of urine (do not perform this exercise during urination unless it is just briefly to learn how to isolate pelvic floor muscles). Squeeze, relax, and repeat. It can be done quickly with high repetitions, or slowly with each contraction held for several breaths. The type of Kegels performed is typically less important than ensuring the exercise is done consistently and correctly. It can take some time and practice to isolate and control the precise muscles. A common mistake is squeezing the glutes instead of the pelvic floor. By combining Kegels with daily activities like driving or brushing teeth, or exercises like crunches and squats, they are more likely to become a regular part of a woman’s routine. Cueing clients to engage or “zip” up through their inner thighs and into their lower abdominals is a helpful way to ensure the correct muscles are involved. This should be the starting position for most exercises.

Even though Kegels are essential for pelvic floor strength, they are just one piece of the puzzle. Increased intra-abdominal pressure is a common justification for why pregnant women and new mothers should abstain from strength training, lifting heavy objects, or working their abdominals because it can cause pelvic floor and abdominal dysfunction along with elevated blood pressure. Trainers can help clients reduce internal pressure and strain on the pelvic floor and abdominal wall by teaching women to avoid the Valsalva maneuver (holding breath and bearing down) and to breathe steadily during physical activity. Simply exhaling during the exertion of each exercise can allow women to remain active and strong throughout pregnancy and postpartum. Women should be encouraged to remain active throughout pregnancy, including exercises to maintain a strong core and pelvic floor, for an array of health benefits including a decreased risk of diastasis recti, incontinence, and other pelvic floor dysfunctions. Water-based exercise is also an excellent no-impact option for women who experience pelvic or lower back pain (Lohmeyer, 2017). The buoyancy of the water can provide much-needed relief in the 3rd trimester.

While there is some risk to the pelvic floor during intense physical activity and heavy lifting, prenatal exercise is a proven way to strengthen the pelvic floor and decrease the need for medical intervention during delivery, which is a significant risk factor for prolapse and incontinence. Women who are nervous about damage to their pelvic floor are sometimes tempted to opt for a cesarean section instead of a vaginal delivery, but a recent meta-analysis concluded that cesareans are not a recommended method of prevention (Keag, Norman & Stock, 2018). There is a strain on the pelvic floor during pregnancy and labor regardless of the type of birth. Consistent exercise and healthy lifestyle behaviors such as proper nutrition, and maintaining a healthy weight before, during and after pregnancy is the best approach.

When working with a client who has recently had a baby, it is important to encourage these new mothers to start slowly and see how they feel. The recommendation of waiting 6-8 weeks before returning to exercise is only a general timeframe and can vary greatly depending on each woman’s personal situation. Asking a client about her birth experience when she returns to exercise can help guide the workout intensity and offer a better understanding of her mental and physical state. Minor tearing of the pelvic floor is common during vaginal delivery and is important to consider during postpartum workouts. More severe tearing will delay the return to physical activity and require a slower progression of workout intensity. In the months postpartum, avoid exercises that require lunging or twisting and focus on regaining strength for basic functional movements, proper body alignment, and posture. Pushing too hard too soon can set a woman back in her recovery. Begin slowly with exercises for the transverse abdominis, pelvic floor, and back while encouraging clients to go at their own pace and listen to their bodies. When she feels ready, slightly increase the intensity and reassess. Each woman’s body and her experience with pregnancy, labor, and delivery will be unique and should be treated as such when designing a fitness program.

References:

Durnea, C.M. et al. (2017). What is to blame for postnatal pelvic floor dysfunction in primiparous women -- Pre-pregnancy or intrapartum risk factors?. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 36. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.04.036

Keag, O. E., Norman, J. E., & Stock, S. J. (2018). Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos Medicine, 15(1), 1.

Lohmeyer, D. (2017). The Benefits of Water-Based Pregnancy Exercise. Australian Midwifery News, 17(4), 40-41.

Neels, H., De Wachter, S., Wyndaele, J., Wyndaele, M., & Vermandel, A. (2017). Does pelvic floor muscle contraction early after delivery cause perineal pain in postpartum women?. European Journal Of Obstetrics And Gynecology, 1.