In previous articles, we examined the first four phases of the Optimum Performance Training (OPT) model. We are now onto the last level and phase of the OPT model: Phase 5 Power Training. Before jumping into the specifics of Phase 5, let’s briefly review the overall structure of the OPT model for NASM-CPTs.

The OPT model consists of three levels subdivided into five phases of training, each focusing on specific physiological adaptions. The three levels consist of stabilization, strength, and power. The phases include Phase 1 Stabilization Endurance Training, Phase 2 Strength Endurance Training, Phase 3 Muscular Development Training, Phase 4 Maximal Strength Training, and Phase 5 Power Training.

Phase 5 is the peak of the OPT model and uses the adaptations of stabilization and strength acquired in the previous phases of training and applies them at more realistic speeds and forces that the body will encounter in everyday life and sport. In other words, we are trying to increase the speed and force of muscle contractions.

Power is defined by force multiplied by velocity (P = F × V ). Therefore, any increase in either force (i.e., strength capabilities) or velocity (i.e., speed of movement) will produce an increase in power. This is accomplished by either increasing the load (or force) as in progressive strength training or increasing the speed with which a load is moved (or velocity). The combined effect is a better rate of force production in both daily and sporting activities.

Getting Technical |

| Rate of force production is affected by increasing the number of motor units activated, the synchrony between them, and the speed that they are excited (Freitas et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Santos & Janeira, 2008). |

As with all the training phases, individuals will typically spend around two to six weeks in Phase 5 before cycling back through earlier phases or implementing an undulating program in which stabilization, strength, and power are trained within the same week. Training in Phase 5 will be up to the discretion of the fitness professional and the client's goals.

Like Phase 4, this phase may not be appropriate for everyone, especially those with chronic health conditions, physical limitations, or those who are averse to high-intensity exercise. Phase 5 is unique compared to the other phases of the OPT model regarding exercise selection and acute variables (sets, reps, rest periods, intensity). Before moving into Phase 5, make sure that your client is physically capable of performing high-intensity exercise and that the adaptations expected in Phase 5 are in line with their goals. We always need to make sure that training is both safe and effective for our clients.

DESIGNING A PHASE FIVE WORKOUT

All programs within the OPT Model follow the same format and consist of identical components. These components include:

All programs within the OPT Model follow the same format and consist of identical components. These components include:

- Warm-Up

- Activation

- Skill Development

- Resistance Training

- Client’s Choice

- Cool-Down

Each component is designed and implemented to help elicit a specific physical adaptation. However, you might not always have adequate time to use them all within a single workout.

It will be up to the discretion of you, the fitness professional, to pick and choose which components are most important for your client. With that said, let's examine each component and how they work within Phase 5.

Warm-Up

Regarding the warm-up, there are two training protocols. The first method is self-myofascial techniques (SMT), a technique used in all five phases of the OPT model. The second training technique is dynamic stretching. Dynamic stretching is optional across the OPT model, so it might not be new to you at this point. If it is, we’ll dive into it in much more detail down below. First, let’s go over the basics for SMT.

SMT is often seen in the gym with individuals using a foam roller or similar device. But what is it? Myofascial rolling focuses on both the nervous and fascial systems in our bodies. SMT has a mechanical and neurophysiological effect on soft tissues, which can help influence relaxation and pain modulation in the local and surrounding tissues (Grabow et al., 2018; Young et al., 2018).

A roller, or other devices, may help relax the local myofascial by increasing blood flow and reducing restrictions in the tissue (Jay et al., 2014). As for programming, the protocols are going to remain the same as in previous phases. You will select one to three different muscles groups and hold any tender spot found for around 30 seconds. Information on what muscles need targeting is based on the assessment (or re-assessment) process.

Muscles identified as “overactive” are targeted during the warm-up to the best of your ability. After finishing SMT, we move to dynamic stretching.

Dynamic stretching is something we briefly discussed in previous articles but not in sufficient detail. This form of stretching uses the force production of a muscle and the body’s momentum to move a joint(s) through its full (available) range of motion (Behm & Chaouachi, 2011).

Dynamic stretching can be a very effective tool for a proper warm-up. It can even replace the use of a cardiorespiratory exercise when it is performed in a circuit fashion. This is especially true before athletic activities because dynamic stretching addresses multiple muscle groups and elevates a client’s heart and respiration rates (Opplert & Babault, 2018). To maximize benefits for your clients, you should program between 3 and 10 different stretches and complete each one for a total of 10 to 15 repetitions.

Below, we can see an example of two different dynamic stretches. The first exercise is a push-up with a rotation and the second one is a multiplanar lunge with reach.

Activation

Much like the earlier phases, Phase 5 activation consists of core and balance exercises. However, these exercises are optional in this stage of the exercise routine because core and balance training can be programmed into the resistance training portion of the workout.

As you can already probably guess, core exercises in Phase 5 should involve explosive movements of the core that are designed to increase the rate of force production. For balance, we should see a continuation of what has been completed in previous workouts. Balance exercises should further develop proper deceleration, proprioception, and eccentric strength, which will help the client improve overall neuromuscular efficiency (i.e., coordination).

Skill Development

Skill development is the inclusion of plyometric and speed, agility, and quickness (SAQ) exercises. Like what we saw in the activation portion of our workout, skill development is also optional in Phase 5. More specifically, plyometric training performed explosively can easily be programmed in the resistance training portion of the workout.

If completed here, these exercises should be a continuation of what was done in earlier phases and focus on, you guessed it, the rate of force production. Moreover, plyometric and SAQ training can also be implemented on a separate day from resistance training. It is up to the discretion of the fitness professional whether to include plyometrics and SAQ training with their clients and athletes. This decision is dependent on the client’s needs, goals, and training schedule.

Resistance Training

When training for power, we will use some of the same training techniques used in Phase 4 Maximal Strength Training. Phase 4 utilizes heavy weight training to increase a client’s force output. Since force production is a vital component of power, Phase 5 also integrates heavy resistance training exercises.

However, we are also striving to increase the client’s rate of force production, meaning speed/velocity is also critical. This combination can be achieved by pairing a strength-focused exercise (heavy resistance training) with a power-focused exercise (high-velocity movements) in a superset. This style of training is also referred to as complex or contrast training.

Combining strength and power-based exercises can increase total power output (Cormier et al., 2020; Freitas et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Santos & Janeira, 2008). The strength-focused exercise improves our client’s force output, whereas the power-focused exercise enhances our client’s ability to maximize the speed of movement/velocity. In other words, through this style of programming, the client is addressing both sides of the power (P = F × V ). The acute variables for both are slightly different, and we’ll cover that in more detail.

Below, you can see an example of a Phase 5 superset. The first exercise (strength-focus) is a barbell bench press, and the second exercise (power-focus) is a medicine ball chest pass. As you can see by these illustrations, we are targeting the same muscle group for each superset.

Client’s Choice

This section of the program is identical to the other phases of training. This section allows our clients to be a part of the decision-making process and choose one to two exercises that they want to do as long as it is both safe and effective. Remember, everything comes down to the discretion of you, the fitness professional.

Cool-Down

The cool-down is a very important component of any successful workout, and it is the same across the entirety of the OPT model. After a workout, make sure to set aside at least 5-10 minutes to allow for a proper cool-down. It is similar in structure to a warm-up and consists of optional cardiorespiratory exercise, SMT, and static stretching (dynamic stretching in Phase 5 is only done in the warm-up).

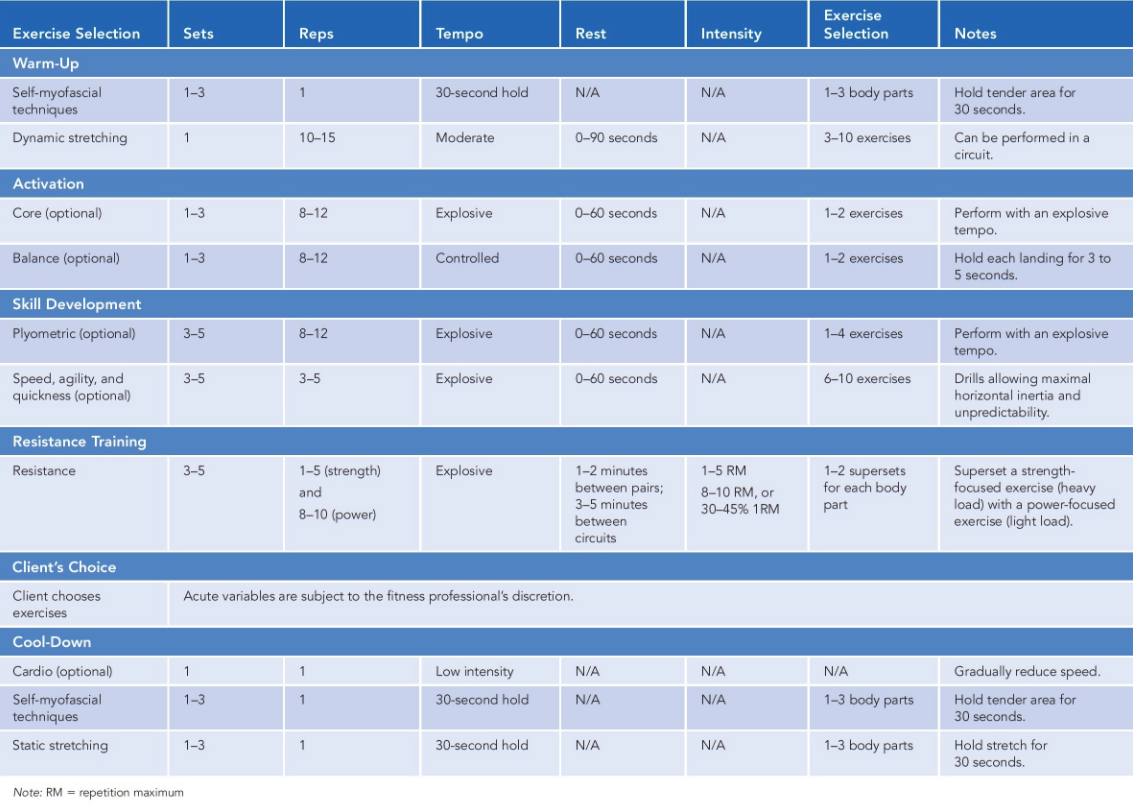

Acute Variables

Below, you will find a complete breakdown of the acute variables of a Phase 5 program. However, understanding the acute variables during resistance training is vitally important and is addressed. The first exercise uses a heavy load, one to five repetitions, which is approximately 85% to 100% of a client’s one repetition maximum. In other words, the first exercise in the superset is a heavy lift that challenges the body to generate high amounts of force.

The second exercise in the superset focuses on developing speed and velocity by using explosive movements with light loads. Implements, such as medicine balls, tubing, and weight vests, are common when performing these exercises. However, bodyweight is also common for many power-based plyometric drills. Light loads (30% to 45% intensity) at high speeds are appropriate intensities.

However, when using a medicine ball, opt for a weighted ball that is no more than 10% of a client’s body weight.

Conclusion

This article completes the breakdown of the final phase of the OPT model. Power is an interesting phase because it is a culmination of all the previous phases, so even though it is the most “intense”, it is simply a product of what came before it. I hope that you now have a good understanding of each of the phases of the OPT model and how they complement one another.

Programming does not need to be complicated. The OPT model provides all the necessary tools required to create a safe and effective program, and it is up to you, the fitness professional, to put it all together.

References

Behm, D. G., & Chaouachi, A. (2011). A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 111(11), 2633–2651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-1879-2

Cormier, P., Freitas, T. T., Rubio-Arias, J. Á., & Alcaraz, P. E. (2020). Complex and contrast training: Does strength and power training sequence affect performance-based adaptations in team sports? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 34(5), 1461–1479. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003493

Freitas, T. T., Martinez-Rodriguez, A., Calleja-González, J., & Alcaraz, P. E. (2017). Short-term adaptations following complex training in team-sports: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 12(6), e0180223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180223

Grabow, L., Young, J. D., Alcock, L. R., Quigley, P. J., Byrne, J. M., Granacher, U., . . . Behm, D. G. (2018). Higher quadriceps roller massage forces do not amplify range-of-motion increases nor impair strength and jump performance. Journal of Strength Conditioning Research, 32(11), 3059–3069. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000001906

Jay, K., Sundstrup, E., Søndergaard, S. D., Behm, D., Brandt, M., Sμrvoll, C. A., . . . Andersen, L. L. (2014). Specific and cross over effects of massage for muscle soreness: Randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 9(1), 82–91.

Li, F., Wang, R., Newton, R. U., Sutton, D., Shi, Y., & Ding, H. (2019). Effects of complex training versus heavy resistance training on neuromuscular adaptation, running economy and 5-km performance in well-trained distance runners. PeerJ, 7, e6787. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6787

Opplert, J., & Babault, N. (2018). Acute effects of dynamic stretching on muscle flexibility and performance: An analysis of the current literature. Sports Medicine, 48(2), 299–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0797-9

Santos, E. J., & Janeira, M. A. (2008). Effects of complex training on explosive strength in adolescent male basketball players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(3), 903–909. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31816a59f2

Young, J. D., Spence, A. J., & Behm, D. G. (2018). Roller massage decreases spinal excitability to the soleus. Journal of Applied Physiology, 124(4), 950–959. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00732.2017