The Optimum Performance Training (OPT) model is a proven training system for CPTs that can help any client reach any goal safely and effectively. It is a system based on human movement science and integrated training principles and validated in research (Distefano et al., 2013).

The OPT model consists of three levels (Stabilization, Strength, and Power), subdivided into five phases; Phase 1 Stabilization Endurance Training, Phase 2 Strength Endurance Training, Phase 3 Muscular Development Training, Phase 4 Maximal Strength Training, and Phase 5 Power Training.

In previous articles, we examined the first three phases of the OPT model. Now, we have come to Phase 4, Maximal Strength Training. When reviewing all of the phases of the OPT Model, I think Phase 4 is the most straightforward. Maximal strength is precisely what it sounds like; we increase the load placed on the body's different tissues to elicit strength adaptations.

In Phase 4, it is essential that the individual lifts progressively heavier loads near or at their maximal intensity, known as a one-repetition maximum (1RM). This training protocol increases the recruitment of motor units, the synchronization between them, and the rate of force production, which is especially prevalent early on in a training program (Duchateau et al., 2006; Gabriel, 2006).

In other words, maximal strength training protocols improve the body’s ability to recruit multiple muscle fibers simultaneously and the strength and rate of the electrical signal sent by the nervous system. The result is a net increase in strength capabilities.

Like other phases of the OPT model, individuals typically spend two to six weeks training in Phase 4. If we follow a linear path, we would transition into Phase Five: Power Training or cycle back through an earlier training phase. As previously stated, it all comes down to your client and what is best for them based on their goals, needs, preferences, and capabilities.

DESIGNING A PHASE FOUR WORKOUT

DESIGNING A PHASE FOUR WORKOUT

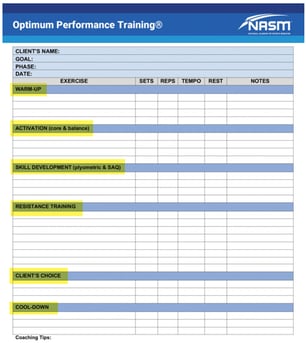

Programming does not need to be complicated. Phase 4, just like all phases in the OPT model, uses the same training components. These components include:

- Warm-Up

- Activation

- Skill Development

- Resistance Training

- Client’s Choice

- Cool-Down

Each component is designed and implemented to help elicit a specific physical adaptation. However, you might not always have adequate time to use each component within a single workout.

It will be up to the discretion of you, the fitness professional, to pick and choose which components are most important for your client. With that said, let's look at a quick breakdown of each and examine how they work within Phase 4 of the OPT model.

It is important to mention that we will see repeated information because Phases 2 through 4 shares many of the same training characteristics. However, there are some significant differences in resistance training which we’ll touch on more later.

Warm-Up

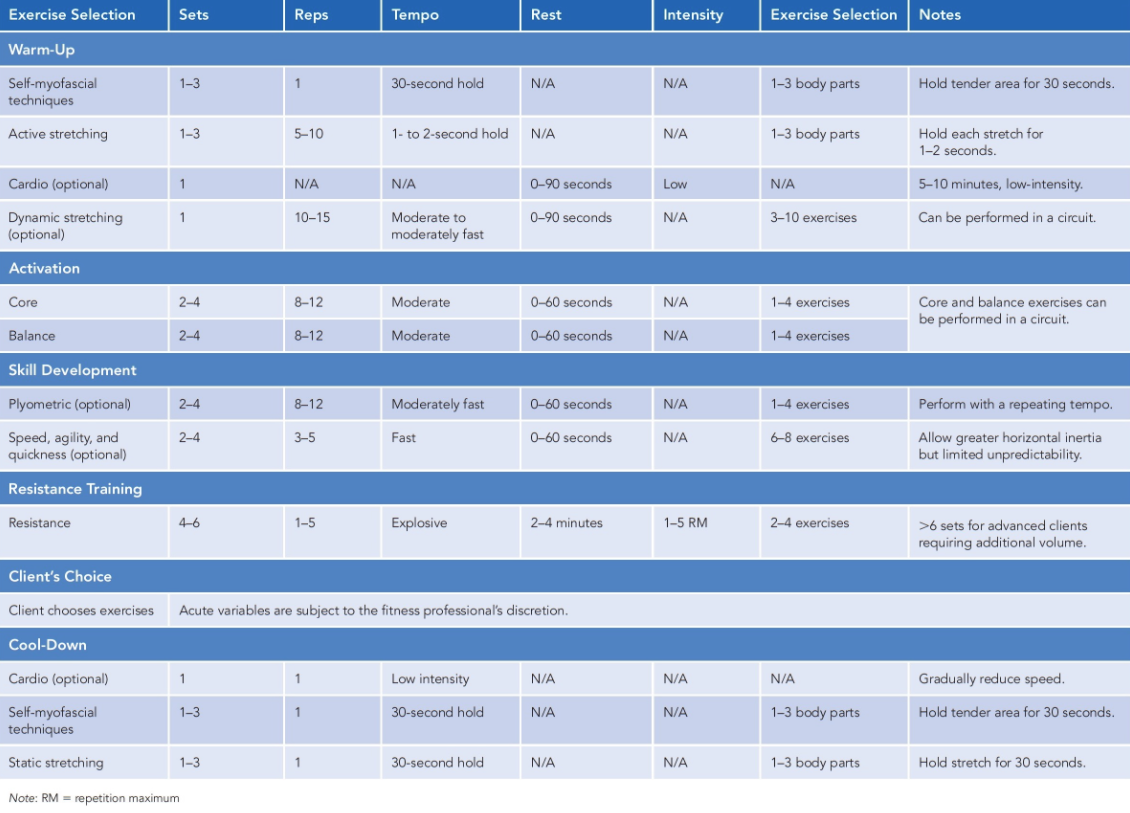

Recall from past blogs in this series that all phases within the strength level of the OPT model (Phases 2-4) share the same warm-up protocols. They consist of self-myofascial techniques (SMT) and active stretching.

Training protocols for SMT stay the same regardless of the phase of training. We want to choose one to three different muscles groups and hold each tender spot for around 30 seconds if using a foam roller. After working through SMT, we make our shift to active stretching. For this particular method of stretching, we are going to choose one to three different stretches. These stretches are “active” and require the individual to complete between 5 to 10 repetitions.

Each repetition should then be held for 1 to 2 seconds. Active stretching uses both the agonist and synergist muscles to help move the targeted joint(s) into the desired range of motion (ROM) (Vernetta-Santana et al., 2015). Active stretching can help increase motor neuron excitability which helps create reciprocal inhibition of the target muscle(s) (Kenny et al., 2019).

Helpful HintRecall that a Phase 1 Stabilization Endurance flexibility routine involves self-myofascial techniques and static stretching. However, in Phases 2 through 4, the flexibility routine is progressed, and flexibility techniques include self-myofascial techniques and active stretching. |

Below we can see an example of both SMT and active stretching for the latissimus dorsi that may appear in a Phase 4 workout.

Like all of the warm-ups before this, we can implement two additional optional training techniques within our warm-up. These include dynamic stretching and cardiorespiratory exercise. Dynamic stretching involves taking a joint(s) through a full range of motion using low-intensity exercises (i.e., bodyweight squats, lunges with rotation, hip swings, arm circles, etc.).

For cardio, we choose an appropriate cardio-based activity for our clients and have them perform it at a low intensity for around 5 to 10 minutes—this portion of our warm-up aims to physically and psychologically prepare the client for high-intensity exercise. Cardio exercise helps increase tissue temperatures, heart rate, respiration rate, and blood flow to working muscles (McGowan et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2018).

Activation

Our next stop is activation. The activation portion of our workout is essentially a continuation of our warm-up. During our warm-up, we used SMT and active stretching to target overactive muscles (identified during the assessment process).

During activation, we are using core and balance exercises to help activate and strengthen underactive muscles. Core and balance exercises help improve performance (Butcher et al., 2007; Dello Iacono et al., 2016; Shinkle et al., 2012), posture (Ko & Kang, 2017; Park et al., 2016), rehabilitation efforts (Coulombe et al., 2017), and can help prevent injury (Huxel Bliven & Anderson, 2013).

During Phase 4, we should be progressing to involving more dynamic movements throughout a full ROM. For core exercises, movements should include flexion, extension, and rotation of the spine when possible. Example core exercises include (but are not limited to) crunches, reverse crunches, cable chops/lifts, and cable rotations.

For balance exercises, movements should progress from a static position (used in Phase 1) to incorporate eccentric and concentric contractions of the balance leg. For example, a single-leg balance exercise can be progressed to a single-leg squat, single-leg Romanian deadlift, or step-ups to balance. When programming, we are looking for one to four exercises with a repetition range of 8 to 12 for a total of two to four sets.

Skill Development

Skill development consists of both plyometrics and speed, agility, and quickness (SAQ) training. Plyometric exercises involve jumps with more amplitude and dynamic motion using a repetitive tempo. Example exercises include (but are not limited to) squat jumps, butt kicks, and tuck jumps. SAQ drills, such as speed ladder exercises and cone drills, require moving faster and increasing horizontal inertia when compared to movements used in Phase 1.

When programming for plyometrics, select one to four exercises and have your client complete 8 to 12 repetitions for a total of two to four sets. SAQ programming uses a repetition scheme of three to five and three to five sets.

Plyometric and SAQ training is optional based on your client’s preferences, available time, and sport needs. For example, clients seeking improvements in maximal strength may not require the expression of agility and quickness for their sport (i.e., bodybuilders).

However, certain strength-based athletes, like those who compete in the shot put, discus, or football linemen, require maximal strength, agility, and quickness. For these athletes, plyometric and SAQ exercises help develop their full expression of athleticism. Depending on the individual’s training schedule, plyometric and SAQ training can be performed on separate days from resistance training.

Resistance Training

The resistance training portion of a Phase 4 program sets it apart from the other phases of the OPT model due to the intense nature of the program. Resistance training in Phase 4 is advanced and should only be completed by experienced lifters, including individuals who have completed the first three training phases of the OPT model. This phase is perfect for athletes (or other individuals) looking to enhance their strength or for individuals seeking improvements in muscular hypertrophy.

Each exercise involves a lower repetition count (one to five) and a much higher set count (four to six), with the intensity at or very close to the client’s 1RM. Tempo is also very important. Clients should use an explosive tempo (X/X/X/X) to lift the weight. However, since the load is so heavy, the actual velocity of the movement appears relatively slow.

Common exercises used in Phase 4 include (but are not limited to) squats, deadlifts, rows, shoulder presses, bench presses, and Olympic Weightlifting. We will cover the acute variables in more detail a little later on.

Client’s Choice

This section of the workout allows your client to choose one or two of their favorite exercises. At this point, any exercise is permitted as long as you, the fitness professional, deem it safe and effective.

Cool-Down

The cool-down is identical across the entire OPT model and should last somewhere between 5-10 minutes. It is very similar to the warm-up and consists of an optional cardiorespiratory component, SMT, and static stretching. Recall, the use of active stretching is used for the warm-up during the strength level of the OPT model, but the cool-down requires static stretching.

The cool-down is a critical component of the workout. As a fitness professional, make sure you set aside enough time to allow your client(s) to cool down properly at the end of each workout. Plus, you can also use this time to discuss the workout and any future plans.

Acute Variables

The acute variables (sets, repetitions, rest periods) can be viewed on a spectrum. On the left side of the spectrum, you have low intensity (high repetitions/few sets/short rest intervals), and on the right side, you have high intensity (low repetitions/high sets/long rest periods) protocols. Phase 4 Maximal Strength Training is pretty much as far right as you can go. You can see a complete breakdown of the different acute variables below.

Conclusion

This article completes the breakdowns of the three different phases of the Strength Level of the OPT model. I hope these articles give you a better idea of what makes up a typical workout program. One of the most important things I want people to take away from these is that programming does not need to be complicated, and we shouldn’t make it that way.

Exercise programming is simply a manipulation of a handful of training modalities and acute variables. Once we understand these, it becomes easy to make a safe and effective workout for anyone. Our next post will cover our final phase of the OPT Model; Phase 5 Power Training.

References

Butcher, S. J., Craven, B. R., Chilibeck, P. D., Spink, K. S., Grona, S. L., & Sprigings, E. J. (2007). The effect of trunk stability training on vertical takeoff velocity. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 37(5), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2007.2331

Coulombe, B. J., Games, K. E., Neil, E. R., & Eberman, L. E. (2017). Core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. Journal of Athletic Training, 52(1), 71–72. https://doi.org /10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.16

Dello Iacono, A., Padulo, J., & Ayalon, M. (2016). Core stability training on lower limb balance strength. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(7), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2015.1068437

Distefano, L. J., Distefano, M. J., Frank, B. S., Clark, M. A., & Padua, D. A. (2013). Comparison of integrated and isolated training on performance measures and neuromuscular control. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 27(4), 1083–1090. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318280d40b

Duchateau, J., Semmler, J. G., & Enoka, R. M. (2006). Training adaptations in the behavior of human motor units. Journal of Applied Physiology, 101(6), 1766–1775. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00543.2006

Gabriel, D. A., Kamen, G., & Frost, G. (2006). Neural adaptations to resistive exercise: Mechanisms and recommendations for training practices. Sports Medicine, 36(2), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636020-00004

Huxel Bliven, K. C., & Anderson, B. E. (2013). Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports Health, 5(6), 514–522. https://doi.org /10.1177/1941738113481200

Kenny, W. L., Wilmore, J. H., Costill, D. L. (2019). Physiology of Sport and Exercise (7th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ko, K.-J., & Kang, S.-J. (2017). Effects of 12-week core stabilization exercise on the Cobb angle and lumbar muscle strength of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 13(2), 244–249. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer .1734952.476

McGowan, C. J., Pyne, D. B., Thompson, K. G., & Rattray, B. (2015). Warm-up strategies for sport and exercise: Mechanisms and applications. Sports Medicine, 45(11), 1523–1546. https://doi.org /10.1007/s40279-015-0376-x

Park, Y. H., Park, Y. S., Lee, Y. T., Shin, H. S., Oh, M.-K., Hong, J., & Lee, K. Y. (2016). The effect of a core exercise program on Cobb angle and back muscle activity in male students with functional scoliosis: A prospective, randomized, parallel-group, comparative study. Journal of International Medical Research, 44(3), 728–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060516639750

Silva, L. M., Neiva, H. P., Marques, M. C., Izquierdo, M., & Marinho, D. A. (2018). Effects of warm-up, post-warm-up, and re-warm-up strategies on explosive efforts in team sports: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(10), 2285–2299. https://doi.org/10.1007 /s40279-018-0958-5

Shinkle, J., Nesser, T. W., Demchak, T. J., & McMannus, D. M. (2012). Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(2), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822600e5