Some fitness trainers see the word “core” as gimmicky and replace it with words like “trunk,” “center” or “column.” Others resist the term because they feel it lacks a clear definition. Here’s an easy, if slightly disconcerting, way to visualize the core: “Unplug” the arms, legs and head, and the core is everything that’s left! In more technical terms, the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex, along with additional muscles that act on the spine, is often considered the “core of the core.” The LPHC includes the lumbar spine, pelvic girdle, abdomen and hip joints. The muscles of the core are, then, any muscles that cross over or directly act upon the LPHC (NASM 2018).

Whatever you call the core, or however you picture it, understanding its function and movements is essential for fitness professionals because this area of the body is the foundation for our ability to produce nearly all movements. If the core cannot support a particular exercise, then the arms and legs involved in it cannot produce the requisite force or speed. Reducing belly fat and increasing stabilization is key! This is why fitness professionals often state that every exercise is a core exercise.

Let's dive into the more granular details of training the core - as found within our core training course.

A Logical, Progressive Approach to Core Training

As with any good regimen, a core training program must be designed to progress exercise participants safely and logically, providing a strong foundation (literally) before introducing strength or power moves. Too often, trainers and clients skip the stabilization phase, opting for more exciting and dynamic movements.

Limits in core stabilization training can impede performance outcomes, as well as structural and movement efficiency, and may ultimately lead to injury or pain. In fact, a lack of core stability and proper mobility may lead to back pain in some people, and providing appropriate exercises to strengthen the core can mitigate such pain (Gomes-Neto et al. 2017).

Our job as personal trainers is not to address or treat pain, but we are well within our limits to address stability and movement deficiencies.

For example, a postpartum client will be approached differently than when we prescribe post-partum core exercises. Assessments for stability and movement deficiencies are key because of the uniqueness of each client.

NASM’s exclusive Optimum Performance Training™ (OPT™) model offers a pathway for progressing functional abilities, including flexibility, core stabilization, balance, strength, power and cardiorespiratory endurance. In this article, we’ll look at stabilization, strength and power in NASM’s OPT model as it relates to core training.

Assessing a Client’s Core Stability

Understanding the movements of the spine is imperative to better understand the core. The spine can be stabilized in all planes, flex and extend in the sagittal plane, flex laterally in the frontal plane (side bend), and perform a combination of these movements in and through multiple planes concurrently (as in a crunch with rotation).

In a core training program, the client should begin at the highest level at which he or she can maintain stability while performing an exercise with proper form.

Various movement assessments can identify whether core stabilization is lacking. Here are some, but by no means all, of the options available:

- double-leg lowering test

- Pushup

- overhead squat assessment (OHSA)

- floor bridge (without arching or rounding the spine)

- quadruped opposite arm/leg raise (bird-dog)

Status and progress are evaluated through reassessments, when the trainer gauges whether the client is ready to progress to more dynamic core exercises.

If you are still wondering about how deep you should delve into core training for your clients, bookmark this video for later!

Core Stability Essentials: Bracing and Drawing In

There are two main types of core stability: intervertebral stability and lumbo-pelvic stability.

Intervertebral stability is the ability to minimize movement between vertebrae. This can be done through activation/facilitation of smaller muscles like the transverse abdominis, diaphragm, pelvic-floor muscles and small paraspinal muscles (such as the multifidus). Exercises include Kegels and drawing in (pulling the navel toward the spine).

Lumbo-pelvic stability is the ability to minimize movement between the rib cage and pelvis. This can be done through abdominal bracing (isometric tightening of the core muscles).

Be sure to begin core training by cuing clients on how to perform the drawing-in maneuver and abdominal bracing, as both are essential for performing core exercises properly and safely.

The Best Core Stabilization Exercises

Stabilization is the first phase of core training, according to the NASM OPT model. At this level, there is little to no movement of the spine. By applying this simple guideline, we can more easily provide a taxonomy for exercise. We can add anti-rotational exercises like these:

- plank (prone iso-abs)

- side plank (side iso-abs)

- floor prone cobra (without spinal extension)

- floor bridge (as long as the spine is not dipping or hyperextended)

- cable anti-rotation

- chest press (Pallof press) (standing or kneeling)

Other exercises that integrate the core are not necessarily core-focused, but they do require the core to remain strong and incredibly stable. For example:

- Pushups

- bent-over rows

- kettlebell swings

- deadlifts

- asymmetrically loaded carries

Just because core stabilization exercises are the first part of a progressive program, that doesn’t mean they’re easy. They can be very difficult to perform and even more difficult to do well. These exercises can also be made increasingly difficult when a trainer adds unstable tools, perturbations and different force vectors.

The Best Core Strength Exercises

Core strength exercises require movement of the spine through relatively large ranges of motion and integrate the full muscle-action spectrum (eccentric, isometric and concentric muscle actions). These movements include flexion, extension, lateral flexion, rotation and a combination of those joint actions.

Exercisers usually start in this phase and rarely leave it. Here are some of the common exercises:

- Crunches

- back extension

- side bends

- trunk rotations

These core-focused exercises can also integrate resistance through the use of bands, cables, medicine balls and free weights. A twist can be added, too, as in cable and medicine ball rotations and back extensions.

"Just because core stabilization exercises are the first part of a progressive program, that doesn’t mean they’re easy. They can be very difficult to perform and even more difficult to do well. "

Core Power Exercises

Core power exercises utilize little to no resistance and focus on the movement’s rate of force production (speed). For most clients and trainers, these exercises are fun, because they usually involve throwing things! Here are some examples, which are typically done with a medicine ball:

- rotation chest pass

- overhead crunch throw

- soccer throw

- medicine ball slam

Be sure to use the right type of ball (as in a wall-ball version of a medicine ball) and to throw against a surface that can take a beating (no drywall!). Even though power training focuses on the explosive concentric phase, we cannot achieve this without eccentrically lengthening, or stretching, the muscles. The idea is to spend as little time as possible transitioning from the stretching phase back into an explosive concentric movement.

With all parts of the muscle action spectrum supported by good core stability and balance, we can develop a high-functioning integrated performance paradigm and stretch-shortening cycle (NASM 2018).

A Workout With Science at Its Core

While some voices within and outside of the fitness industry have expressed concern over the potential negative impact of core exercises on the lower back, “numerous studies … support the role of core training in the prevention and rehabilitation of low back pain” (NASM 2018). So, you should not be afraid of core exercises, and neither should your clients.

Of course, any exercise that causes back pain should be avoided, be it a core stability exercise like a plank; a core strength exercise like a crunch; or a core power exercise like a rotation chest pass. Otherwise, placed within a well-designed progressive and systematic training protocol such as the NASM OPT model, these moves are fine. In fact, when clients follow this type of program, they can develop a core musculature that protects the spine during workouts as well as everyday activities.

FACQ: Frequently Asked Core Questions

Here are some answers to have ready, as you’re likely to hear these queries at some point in your career!

Can I work my abs every day?

The rectus abdominis, erector spinae, obliques and all other core muscles are similar to every other muscle in that they need time to recover from intense workout bouts. Because the core is an integral part of all functional workouts, you will be working it to some extent in any such sessions. But if you do a more focused and exhaustive core workout on a particular day, take the next day off so your core can recover.

Are there really “upper” and “lower” abs?

Only when it comes to location, not function. For instance, is there an upper part and a lower part of an escalator? Sure, but the escalator, like the rectus abdominis, works as one unit. People may feel their “lower abs” during leg lifts and knee tucks, but as someone once said, “Feelings aren’t facts.” That sensation is caused by the psoas muscles that anchor to T12–L5, which happen to be under the lower portion of the rectus abdominis.

Will core training give me a six-pack?

Reasons for working on core muscles should not include the statement “So I can see my abs.” Core muscles do hypertrophy, but not well. And there is little to no chance that clients will see their abs without losing fat in the midsection. Core exercises will improve function and performance, but it is weight loss that helps abdominals become more visible.

See also: How to Really Get a Six Pack

Sample: Progressive Core Workout

The following program was created using the NASM OPT™ model. NASM recommends that core exercises be done early in the workout—after the warmup and before the resistance training portion—to activate or “wake” the core musculature. However, when core exercises precede resistance training, they should not be performed to the point of exhaustion, or it defeats the purpose.

LEVEL 1

CORE STABILIZATION EXERCISES

1–3 sets of 10–15 reps per side at a slow tempo.

Side Plank (Side Iso-Abs)

Draw in and lift, holding for 5 seconds with purposeful engagement of the core and leg musculature. Keep the head, shoulders, hips, knees and feet in a straight line.

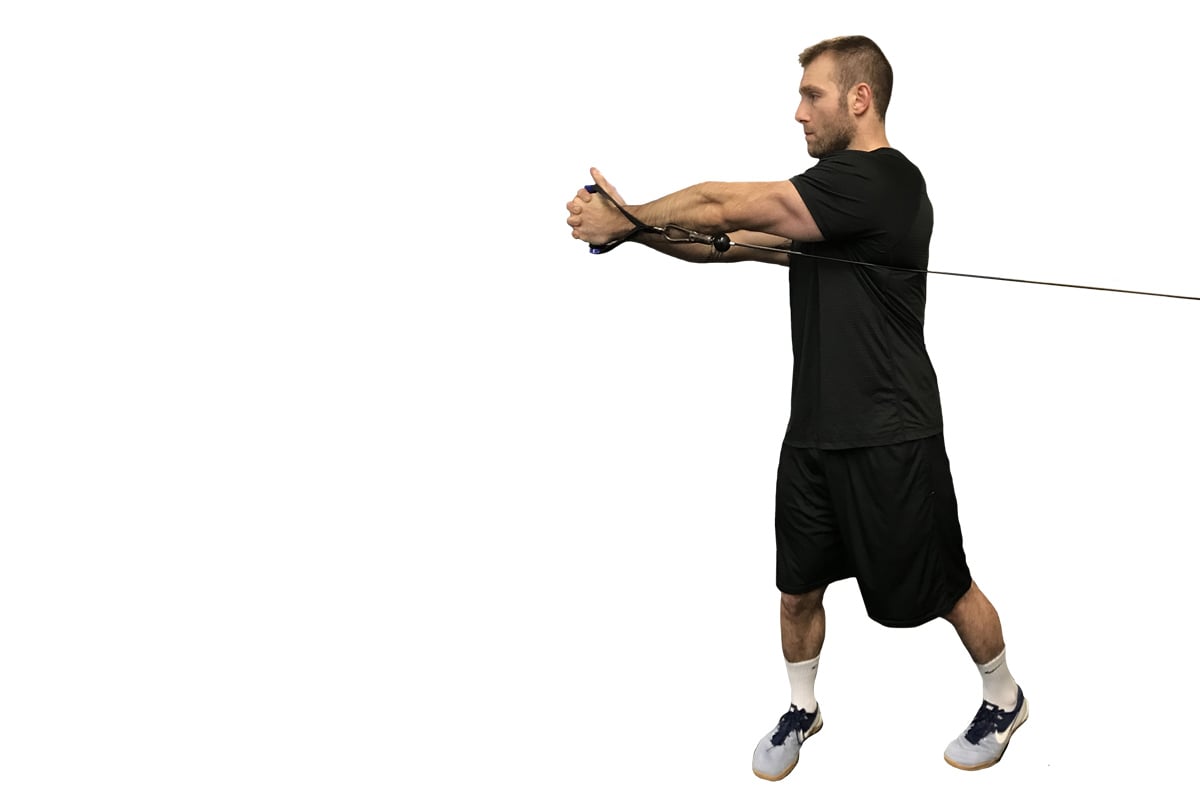

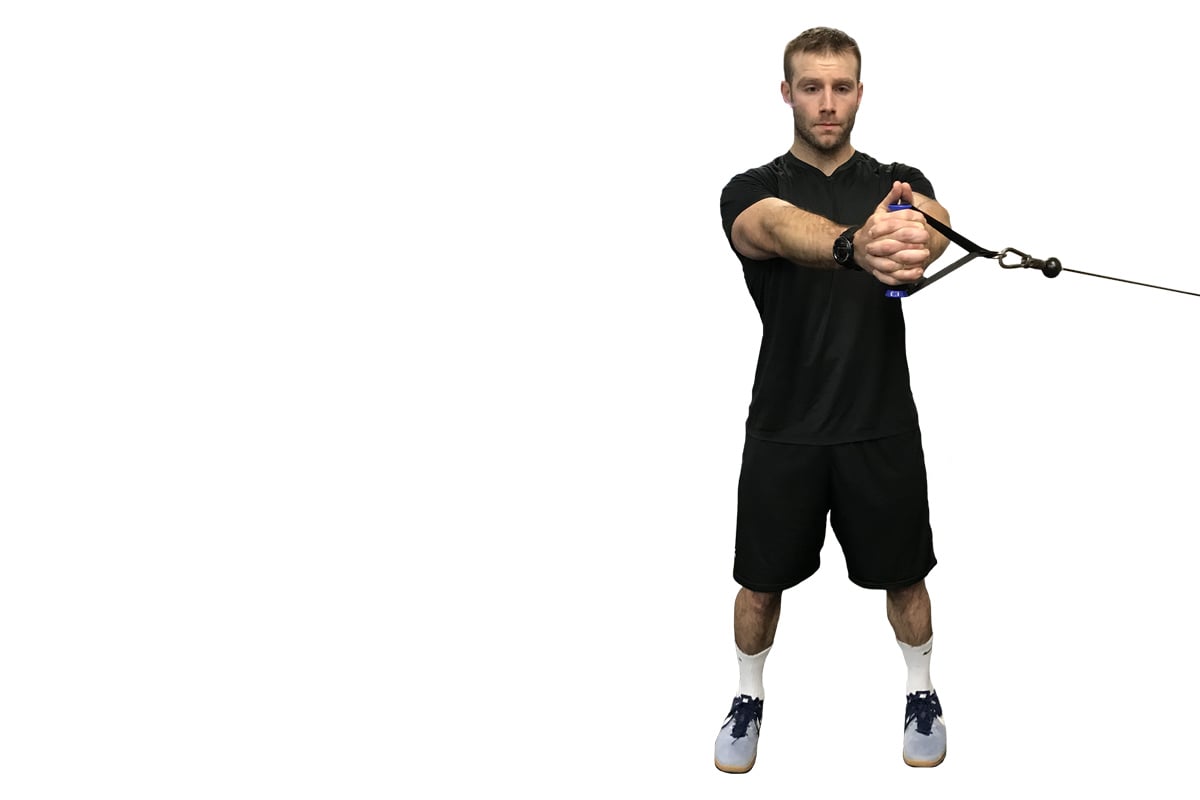

Cable Anti-Rotation Chest Press (Pallof Press)

With resistance anchored to the side, stand with the feet hip- to shoulder-width apart, and hold the handles at chest height. (The narrower the stance, the more difficult.) Draw in the navel, tighten the core muscles and engage the glutes.

Press the handles away from the center of the chest, avoiding any movement or rotation of the LPHC during the exercise.

LEVEL 2

CORE STRENGTH EXERCISES

2–3 sets of 8–12 reps at a medium tempo.

Cable Rotation

This progression adds spinal and hip rotation. The torso stays tall, chest up. Tip: Cue clients to think of the trunk as the perturbator in a top-loading laundry machine, spinning around a single axis without tilting.

Stability Ball Back Extension

Brace feet against the wall or a stable machine, and align the ball low on the abdominal region.

Flex the spine over the ball, and then extend using the erector spinae muscles while still holding the glutes and leg muscles tight.

LEVEL 3

CORE POWER EXERCISES

2–3 sets of 8–10 reps, as fast as possible with control.

Note: Use light weight so that every rep is as fast as the previous. Once slowdown occurs, there is no longer coding to increase the rate of force production.

Medicine Ball Rotation Chest Pass

This progression from the cable rotation exercise focuses on lighter weights (a ball) so that the throw can be explosive, since that is how power is developed. Stand sideways, about 3–5 feet away from the wall, feet parallel to the wall.

Twist the body 90 degrees (chest is now facing the wall) while explosively throwing the ball against the wall. (Choose a type of ball that will not damage the wall on impact.)

Medicine Ball Slam

This is a good core power exercise, not because the spine is going through much of a range of motion, but because the core is the link in an explosive upper- and lower-body movement.

Lift the medicine ball overhead.

Then use the entire body to accelerate the ball down to the floor or mat.

REFERENCES

Gomes-Neto, M., et al. 2017. Stabilization exercise compared to general exercises or manual therapy for the management of low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physical Therapy in Sport, 23, 136–42.

NASM (National Academy of Sports Medicine). 2018. NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.