Shoulder pain, prior injury, or overall dysfunction is a very common problem in both the athletic and general populations in a personal training practice. A complaint of shoulder pain occurs in 16 to 26 percent of adults and is the third most common musculoskeletal issue seen in many primary care settings.Shoulder pain can arise from any of the structures in the shoulder including the glenohumeral, scapular, and acromioclavicular joints, tendons, and muscles, (Mitchell et al., 2005). The shoulder joints, especially the glenohumeral joint, are very mobile and hence are prone to instability and injury.

The shoulder is the focal point of chapter 14 of the NASM Corrective Exercise Specialization. Check out the course to learn more!

What Causes Shoulder Pain?

The shoulder is a complicated system of several joints and muscles. Any breakdown in the system so to speak can results in pain. Although acute injuries (such as shoulder trauma or infection) can cause pain, this article is more focused on the main causes and treatment of chronic shoulder pain which can be broken down into three main categories (Mitchell et al., 2005).

Rotator cuff disorders

The rotator cuff is the group of small muscles that anchors the glenohumeral joint in place. These muscles include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. These muscles are composed of mostly type I muscle fibers and are responsible for movements of the glenohumeral joint such as internal rotation (subscapularis), abduction to 15 degrees (subscapularis), and external rotation (infraspinatus), external rotation (teres minor).

Rotator cuff disorders include any injury or problem that affects these muscles and their supporting structures (Smita Maruvada & Varacallo, 2018). These conditions include impingement, rotator cuff tears, bursitis, or rotator cuff tendinopathy (Varacallo et al., 2022).

Rotator cuff disorders are relatively common in clients between the ages of 35 and 75. These disorders can cause pain and/or weakness in the shoulder, typically towards the front and side. Specific movement tests can give a healthcare provider a better idea of a specific diagnosis, but oftentimes it can be difficult to figure out.

Glenohumeral joint disorders

These conditions include osteoarthritis (most common over 60 years old) and frozen shoulder or adhesive capsulitis which occurs most commonly between the ages of 40 and 65 years old. Both disorders significantly restrict the movement of the glenohumeral joint.

A frozen shoulder occurs when inflammation occurs within the joint capsule reducing mobility and allowing for scar tissue formation which further limits mobility (Mezian & Chang, 2020). Osteoarthritis occurs when the cartilage cushioning the joint erodes, the joint space narrows, and eventually bone contacts bone with every movement resulting in pain (Mitchell et al., 2005).

Referred pain from the neck

Pain in the shoulder originating from the neck is a very common finding. Many cases of referred neck pain to the shoulder come from having the forward head position which is common with “text neck”.

The forward head position is caused by constantly looking downwards (oftentimes at a phone) and maintaining a rounded shoulder posture. This leads to overactivity in the upper trapezius, levator scapulae, scalenes, and sternocleidomastoid and underactivity in the cervical flexors, middle/lower trapezius, and rhomboids. This complex hinders sound posture and often leads to pain in the neck and shoulders (Clark et al., 2014).

Preventing Shoulder Pain with Corrective Exercise

The good news about chronic shoulder pain is that corrective exercises, when performed consistently, can help prevent and provide improvement for several of these conditions. Often times, a series of overactive and underactive muscles can lead to poor movement patterns with the shoulder which lead to pain or injury, especially with repetitive movements which may be seen in some occupations such as construction, office work, etc.

Likewise, an underactive rotator cuff can be prone to injury as it will fail to stabilize the glenohumeral joint during larger movements such as throwing or pitching. A common injury amongst baseball players is a torn rotator cuff as the prime movers (i.e., deltoids) exert high force on a relatively weak rotator cuff which fails to stabilize the movement (Varacallo et al., 2022).

Mehri et al. (2020) assessed the effectiveness of a corrective exercise program to improve neck and shoulder pain stemming from a forward head position in a cohort of 32 women. The researchers determined that there was a significant improvement in ratings of pain and disability as well as postural alignment in nearly all the women in the intervention group.

Similarly, researchers also found that even a home-based corrective exercise program aimed at improving shoulder and scapular stability proved to significantly decrease pain and symptoms of subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tendinopathy in a group of construction workers engaged in chronic overhead work (Ludewig, 2003).

Many of these same corrective exercises can be applied with most of the shoulder pain conditions listed. They also require minimal equipment to perform.

Top 10 Exercises to Prevent/Correct Shoulder Pain:

- Self Myofascial Release (SMR) of the Latissimus Dorsi and Pectoralis major and minor

- Self Myofascial Release (SMR) of the Upper Trapezius and Levator Scapulae

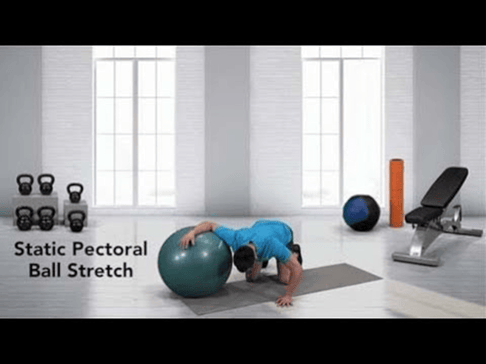

- Static pectoral ball stretch and pectoralis minor stretch

- Latissimus dorsi static ball stretch

- Upper trapezius and levator scapulae static stretch

- Chin tucks

- Blackburn T

- Standing external rotation

- Stability Ball Blackburn Y

- Squat to Row

Note that these exercises can be completed in this order to maintain the corrective exercise continuum of inhibit, lengthen, activate, and integrate (Clark et al., 2014).

Exercise 1: Self Myofascial Release (SMR) of the Latissimus Dorsi and Pectoralis major and minor

SMR Latissimus Dorsi (Lats)

Place foam roller under the affected arm and lean back slightly until a tender spot is found. Extend arm fully. Maintain for 30-60 seconds.

Place foam roller under the affected arm and lean back slightly until a tender spot is found. Extend arm fully. Maintain for 30-60 seconds.

Self-Myofascial Release SMR Pectoralis Major and Minor

This exercise can be completed either from the floor in a prone position or from the wall in a standing position if it is too painful. Oftentimes a foam ball or tennis ball works best for targeting these muscles. Place the ball between the arm and the sternum and find an area of tenderness. Maintain pressure for 30-60 seconds. You can roll the ball around or move your arm up and down as the ball maintains pressure on the muscles.

This exercise can be completed either from the floor in a prone position or from the wall in a standing position if it is too painful. Oftentimes a foam ball or tennis ball works best for targeting these muscles. Place the ball between the arm and the sternum and find an area of tenderness. Maintain pressure for 30-60 seconds. You can roll the ball around or move your arm up and down as the ball maintains pressure on the muscles.

Exercise 2: Self Myofascial Release (SMR) of the Upper Trapezius and Levator Scapulae

This exercise is best completed with hook shaped tool. Put pressure along the upper trapezius until tender spots are found. Maintain pressure on the tender area and turn the head the opposite direction. Maintain for 30 to 60 seconds. Repeat several times over several areas.

Exercise 3: Static pectoral ball stretch and pectoralis minor “crucifixion” stretch

A large foam roller is placed under the back and arms are placed at the level of the ear with a 90-degree bend at the elbow joint. Hold this position for 3- to 60 seconds. Note that a lot of clients will not have the range of motion for their hands to contact the floor, but it is a goal to work towards.

The arm is placed with hand slightly above the hear and lower arm is placed on the stability ball. Allow the chest to sink down until a stretch is felt in the pectoralis major. Hold the stretch for 30 to 60 seconds.

Exercise 4: Latissimus dorsi static ball stretch

The glenohumeral joint and elbow joint are fully extended and the lower arm is placed on the stability ball (close to the wrist). Sink slightly until a stretch is felt in the latissimus dorsi. Hold the stretch for 30 to 60 seconds.

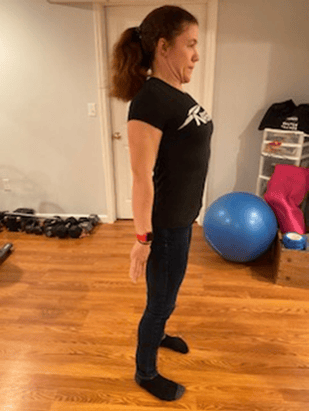

Exercise 5: Upper trapezius and levator scapulae static stretch

Place the opposite hand on the top of the head and gently stretch the upper trapezius as seen in image 1. Gently lean the head back and turn the opposite direction of the targeted muscle.

Exercise 6: Chin tucks

Stand up with an upright posture, retract the shoulder blades, and pull the chin straight back. Hold the position for 2 seconds, slowly release, and repeat for the desired number of repetitions.

Exercise 7: Blackburn T

Lay down in a prone position. Fully extend the arms in a “T” position. Retract the shoulder blades to move the arms off the floor. Hold the position for 2 seconds, slowly release, and repeat for the desired number of repetitions. Note that your client’s range of motion for this exercise will improve with practice over time.

Exercise 8: Standing external rotation

Bend elbow to 90 degrees and anchor as close to the body as possible. Grab resistance band or cable and externally rotate the arm being sure that the shoulder blade is moving.

Exercise 9: Stability Ball Blackburn Y

Place stability ball under the chest in a prone position. Put the arms in a Y position and raise the arms to the level of the ears while keeping the elbows extended. Cue your client to move their arms rather than move their chest off the ball.

Place stability ball under the chest in a prone position. Put the arms in a Y position and raise the arms to the level of the ears while keeping the elbows extended. Cue your client to move their arms rather than move their chest off the ball.

Exercise 10: Squat to Row

Grip a resistance band or cable machine. Retract the shoulder blades and bend the elbows to create a rowing motion. Release and squat. Stand up and repeat for the desired number of repetitions.

Should You Exercise Your Shoulder if It Hurts?

The answer to this question depends on the specific injury sustained, surgical history, and advice from a healthcare provider. Many chronic shoulder injuries will benefit greatly from corrective exercise which can be completed safely.

However, if shoulder pain is present, especially in the case of rotator cuff disorders, it is often advised that overhead, and sometimes, forward pressing movements are avoided until the pain improves (Mitchell et al., 2005).

In my own practice as a certified personal trainer, I will often continue to use the for clients with shoulder injuries, however, their programs will be adjusted to include corrective exercises, and other exercises which may increase pain/injury are omitted or significantly modified.

Original Program

Phase 2: Strength Endurance

|

SMR: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min Active Stretches: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min |

1 set, 30-60 seconds 10 reps |

|

Core/Balance/Plyometric Reverse Crunch |

2 sets, 10 reps |

|

Resistance Barbell Back Squat |

2 sets 10 reps 12 reps 10 reps 12 reps 10 reps 12 reps 10 reps 12 reps |

|

Cool-down SMR: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min Active Stretches: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min |

1 set, 30-60 seconds 1 set, 30-60 seconds |

*The same client suffers a rotator cuff partial thickness tear at a pickup game of baseball. The client has undergone physical therapy and has clearance for exercise but is told to avoid heavily loading the upper trapezius and overhead movements.

Modified Program

Phase 2: Strength Endurance

|

SMR: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min, upper trapezius, levator scapulae Static Stretches: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min, upper trapezius, levator scapulae |

1 set, 30-60 seconds 30 to 60 seconds |

|

Core/Balance/Plyometric Reverse Crunch Banded Abduction |

2 sets, 10 reps |

|

Resistance Leg Press |

2 sets 10 reps 12 reps 12 reps 12 reps 12 reps 12 reps 12 reps 12 reps |

|

Cool-down SMR: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min, upper trapezius, levator scapulae Static Stretches: Calves, Quads, Lats, Pecs maj/min, upper trapezius, levator scapulae |

1 set, 30-60 seconds |

The OPT model is still used, but corrective exercises are programmed into the existing program and still include all components of the corrective exercise continuum. The client will still receive the benefit of training the uninjured muscles, while performing appropriate exercises to help regain function from the injury. Likewise, activities such as walking, cycling, and even dance may be perfectly fine to continue if they are not aggravating the injury.

Are There Special Considerations for Senior Populations?

As many as 30 to 36 percent of seniors will report pain or mobility limitations with their shoulders. However, this is an issue often overlooked by healthcare providers cuff injuries are common as is osteoarthritis. Corrective exercise can be highly beneficial in improving the quality of life for seniors as shoulder injuries can cause significant difficulty in completing activities of daily living in many seniors (Burner et al., 2014).

Conclusions

A well-designed corrective exercise program can be extremely helpful in preventing and reducing the symptoms of shoulder dysfunction. There is a lot of overlap in corrective exercises that will improve a variety of shoulder conditions from rotator cuff tendinopathy to bursitis.

Similarly, many exercises designed to optimize upper body movement patterns require little equipment and can be easily incorporated into a regular resistance training program using the OPT Model.

Be sure to also check out exercises for knee pain to learn more about the necessary corrective exercises to prevent injury.

References

Burner, T., Abbott, D., Huber, K., Stout, M., Fleming, R., Wessel, B., Massey, E., Rosenthal, A., & Burns, E. (2014). Shoulder Symptoms and Function in Geriatric Patients. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy (2001), 37(4), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182abe7d6

Clark, M. A., & Sports, O. (2014). NASM essentials of corrective exercise training. Burlington Jones & Bartlett.

Ludewig, P. M. (2003). Effects of a home exercise programme on shoulder pain and functional status in construction workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(11), 841–849. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.11.841

Mehri, A., Letafatkar, A., & Khosrokiani, Z. (2020). Effects of Corrective Exercises on Posture, Pain, and Muscle Activation of Patients With Chronic Neck Pain Exposed to Anterior-Posterior Perturbation. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 43(4), 311–324.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2018.11.032

Mezian, K., & Chang, K.-V. (2020). Frozen Shoulder. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482162/

Mitchell, C., Adebajo, A., Hay, E., & Carr, A. (2005). Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ, 331(7525), 1124–1128. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1124

Murphy, R. J., & Carr, A. J. (2010). Shoulder pain. BMJ Clinical Evidence, 2010, 1107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217726/

Park, J.-Y., Kim, J., Lee, J.-H., Oh, K.-S., Chung, S. W., & Park, H. (2019). Does a Partial Rotator Cuff Tear Affect Pitching Ability? Results From an MRI Study. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 7(11), 232596711987969. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967119879698

Smita Maruvada, & Varacallo, M. (2018, November 14). Anatomy, Rotator Cuff. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441844/

Varacallo, M., El Bitar, Y., & Mair, S. D. (2022). Rotator Cuff Syndrome. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531506/#:~:text=Rotator%20cuff%20syndrome%20(RCS)%20describes