EPOC is the acronym for Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption. Many refer to it as the "afterburn." To better understand how EPOC works, let's review the basics of energy systems.

Note: If you wanting to eventually transition into a career as a personal trainer, EPOC is an important concept to familiarize yourself with.

Energy Systems 101

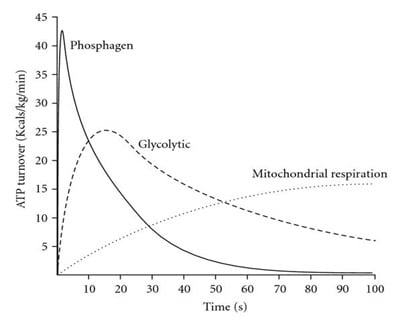

There are three energy systems:

1. Phosphagen (ATP-PC)

2. Glycolytic

3. Oxidative

All three energy systems work during physical activity with varying involvement, depending on the action's duration and intensity.

Phosphagen (ATP-PC) System

The phosphagen (ATP-PC) system harnesses ATP for highly intense activities lasting 10 to 30 seconds, e.g., jumping, sprints, and plyometric exercises.

The Glycolytic System

The glycolytic system uses carbohydrates to produce ATP for activities lasting 30 seconds to 3 minutes, e.g., boxing rounds.

Both the phosphagen (ATP-PC) and glycolytic systems occur in the cell's cytosol and are anaerobic. The end product of glycolysis is pyruvic acid. When oxygen is present (aerobic respiration), pyruvate enters the mitochondria for oxidative metabolism.

In the absence of oxygen, it ferments to produce lactic acid. Lactic acid produced in muscle cells is transported through the bloodstream to the liver, where it is converted back to pyruvate.

The Oxidative System

The oxidative system is aerobic. It occurs in the mitochondria and uses oxygen to help with energy production. Whereas the glycolytic system uses carbohydrates to generate energy, the oxidative system uses fat and protein. This system comes into play during low- to moderate-intensity activities, e.g., distance running.

(Baker, J. S., McCormick, M. C., & Robergs, R. A., 2010)

Through the phosphagen (ATP-PC) and glycolytic pathways, High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) stimulates EPOC.

You can find even more information about the energy pathways by following the link provided!

What is EPOC?

EPOC is the result of an elevation in oxygen consumption and metabolism (Resting Energy Expenditure), which occurs after exercise as the body recovers, repairs, and returns to its pre-exercise state. This can happen for up to 24 hours, according to some sources.

The extent and duration of EPOC are dependent on the workout intensity, i.e., High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), where ATP is required from anaerobic pathways.

EPOC is similar to METS in concept.

Physiologically, EPOC results in:

1. Re-synthesis of lactate to glycogen.

2. Re-oxygenation of myoglobin in muscles and hemoglobin in the blood.

3. Increased respiration.

4. Increased heart rate.

5. Elevated neurotransmitters and catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline).

6. Elevated hormones (cortisol, insulin, ACTH, thyroid, and GH).

7. Elevated core temperature.

(Foureaux, G., Pinto, K. M. D. C., & Dâmaso, A., 2006; Paoli, A., Moro, T., Marcolin, G., 2012)

How to Measure EPOC

Indirect calorimetry is a sensitive, accurate, and noninvasive measurement of Energy Expenditure (EE). It is calculated by measuring the amount of oxygen used (VO2) and carbon dioxide released (VCO2) by the body. The ratio of CO2 produced to O2 consumed is called the Respiratory Exchange Ratio (RER) and is measured by the gas exchange. The RER is a useful indicator of the type of fuel (fat vs. carbohydrate) that is being metabolized.

During carbohydrate metabolism, there is an equal amount of CO2 produced for O2 consumed (RER = 1.0). During fat metabolism, there is less CO2 produced for O2 consumed. As you may recall from the review of energy systems above, higher intensity exercise requires carbohydrates as the primary substrate, thus a higher RER indicates higher intensity and EPOC.

Calorimeters such as multicomponent metabolic carts can be used to measure the RER and the extent of EPOC. These encompass different devices such as a hood/mouthpiece, gas analyzers, and mixing chambers that measure one's breath by breath minute ventilation, while at the same time a sample of gas is conveyed to the analyzer, and VO2 and VCO2 are measured and converted in energy expenditure.

(Gupta, R. D., et al., 2017)

From a logistical standpoint, most people don’t have access to calorimeters, so using the RPE and exercise parameter described above is a more practical way of determining whether your activity is intense enough to elicit an EPOC response.

Practical Application of EPOC

There are many ways to incorporate HIIT into an exercise plan to take advantage of the EPOC effect. Start with choosing an exercise you enjoy, e.g., running, biking, jumping rope, weight training.

After a 15-20 minute warm-up, e.g., foam rolling, active or dynamic stretching, core activation, and low-intensity aerobic activity, choose one of the following:

● Stationary bike. Pedal as hard and fast as possible for 30 seconds, then pedal at a slow, easy pace for one to two minutes. Repeat for 15 to 30 minutes.

● Sprint as fast as you can for 20-30 seconds, then walk or jog at a slow pace for one to two minutes. Repeat for 10 to 20 minutes.

● Jump rope as quickly as possible for 30 seconds, then walk in place for one to two minutes. Repeat for 10 to 20 minutes.

● Tabata-style weight lifting workout: Pull-ups, push-ups, bodyweight squats. Perform 20 seconds on each exercise with a 10-second rest in between x 3-4 sets. - See Tabata Workout Benefits

● Strength training with compound, multi-joint exercises or a resistance training circuit that alternates between upper- and lower-body movements results in greater demand on the anaerobic system during work intervals and an increased demand on the aerobic system to replenish that ATP during the rest intervals and post-exercise recovery process. Shorter recovery intervals also increase the demand on the anaerobic energy pathways during exercise, yielding a greater EPOC effect during the post-exercise recovery period.

Manipulating the tempo (work/rest intervals) and intensity as described above is essential to stimulate the EPOC adaptations.

The Benefits of HIIT and EPOC

1. Time-efficient way to burn calories - HIIT can result in 25–30% more calories burned than other exercise forms. (Falcone PH et al., 2015)

2. Elevated metabolism - HIIT has an impressive ability to increase metabolic rate for hours after exercise. (Wingfield HL et al., 2015)

3. It can help with fat loss (to some extent)- Body fat can be reduced with HIIT, despite the relatively low time commitment. (Sijie T, Hainai Y, Fengying Y, Jianxiong W., 2012)

4. Muscle gain - HIIT training can result in increases in muscle mass in the muscles being used. (Osawa Y et al., 2014)

5. Improved oxygen consumption - Eight weeks of exercising on the stationary bike using HIIT increased oxygen consumption by about 25%. (Skutnik BC et al., 2016)

6. Reduced heart rate and blood pressure - A growing body of evidence shows an improvement in cardiometabolic factors. (Batacan, R. B., et al., 2017)

7. Blood sugar reduction - HIT appears to improve metabolic health, particularly in those at risk of or with type 2 diabetes. (Jelleyman C et al., 2015)

See this resource for great HIIT Workout ideas.

HIIT vs. Steady State

HIIT involves working at about 80%-95% of your maximum heart rate. Work sets are followed by a recovery period where you allow your heart rate to recover down to about a level 2-3 Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE). Work and rest intervals are alternated for 20 to 60 minutes.

Pros and Cons of HIIT Training

Pros

● Improved performance.

● Improved insulin sensitivity.

● Improved calorie afterburn.

● Better for burning belly fat.

● Improved cardiometabolic markers.

● Shorter workouts.

Cons

● Can be uncomfortable.

● Not for beginners.

● Risk of injury.

● Risk of burnout or overtraining due to increased stress on the nervous system and inadequate rest and recovery (using HRV can be an effective way to monitor your training stress).

(Villegas, J. G., 2020)

Steady-State Cardio Training

Steady-State Cardio is moderate-intensity cardio that involves exercising at a consistent speed and one level of intensity for the entire workout, generally at a 4-5 on the RPE scale.

Pros and Cons of Steady-State Training.

Pros

● Less stress on the cardiorespiratory system.

● Increased endurance.

● Improved health.

● Faster recovery.

● Improved ability to use fat for fuel.

● Increases slow-twitch muscle fibers.

● It can be more enjoyable.

Cons

● Time-consuming.

● Risk of overuse injury.

● Can be boring.

● Can cause weight-loss plateaus.

(O'Keefe, J. H., O'Keefe, E. L., & Lavie, C. J., 2018)

Stage Training

The NASM OPT model consists of three building blocks: Stabilization, Strength, and Power. It integrates training to include: Core, Balance, Reactive, Cardiorespiratory, SAQ, and Resistance exercise.

Incorporating HIIT into your routine should be done in a periodized fashion. A fashion in which a base of conditioning is established (stabilization) and then progressively periodized to more intense blocks (strength and power - HIIT). From a cardiorespiratory perspective, this is known as Stage Training.

Stage I:

● Maximal heart rate of 65-75% HRmax or 2-4 RPE.

● Start slowly and gradually work up to 30-60 minutes uninterrupted.

● Once Stage I intensity can be maintained for at least 30 minutes, 2-3 times per week, progress to Stage II.

Stage II:

● Maximal heart rate of 65-85% HRmax or 4-6 RPE.

● Interval training with a work-to-rest ratio of 1:3, progressing to 1:2 and eventually 1:1.

Stage III:

● HIIT involving short, intense bouts of exercise (i.e., sprinting) interspersed with active bouts of recovery (i.e., light jogging).

● Use intervals ranging from 65-95% of HRmax, or 7-9 RPE.

The time needed to transition to Stage III training is variable. It may require 2-3 months or longer and should involve a progressive overload.

How to Determine your HRmax:

HRmax is a simple way of gauging your maximum heart rate. Start by subtracting your age from 220. Use the result to calculate your range by taking the appropriate percentage.

For example, a 55-year-old would have an HRmax of 220-55=165. For a HIIT workout, the work intensity would be 0.95x165=157, and the active recovery would be 0.65x165=107.

Using the Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale (RPE 10-point scale):

0 – No exertion at all / at rest

1 – Very light

2 – 50% effort; reasonably light, gentle walking

3 – 60% effort; light, but still comfortable

4 – 65% effort; moderate, steady pace. Able to comfortably carry on a conversation

5 – 70% effort; somewhat hard, but can still talk continuously with relative ease

6 – 75% effort; vigorous, but still maintainable. Able to talk but only in shorter sentences

7 – 80% effort; hard—talking in shorter sentences is now challenging

8 – 85% effort; very hard. Exercise is becoming difficult and speaking in only short sentences/phrases is possible

9 – 90-95% effort; very, very, difficult—can only speak a few words between breaths

10 – 95-100%; maximum effort—extremely difficult and speaking is impossible

EPOC and Weight Loss - No Magic Bullet

While there are some claims about the effectiveness of EPOC for weight loss, the research on weight loss continues to support that this is an energy issue, whereby energy intake (EI) exceeds energy expenditure (EE). Rather than focusing on EPOC, the focus should be a combination of increased EE through exercise and non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) and calorie restriction.

The combination of resistance training and HIIT may be more advantageous than steady-state cardio for weight loss as this supports the accretion of lean body mass, a factor in maintaining a healthy metabolism. (Arney, B. E., Foster, C., & Porcari, J., 2019)

Conclusion

Exercise adaptations are specific to the imposed demands (SAID Principle). HIIT and the concomitant EPOC can be part of an integrated exercise program; however, one should consider their exercise goals and if HIIT training can be used, in part, to achieve those goals, or if it will adversely affect recovery and predispose one to injury and over-training.

With this in mind, if you are looking for a time-efficient way to burn calories, increase metabolism, increase lean body mass, improve oxygen consumption, reduce heart rate and blood pressure, and improve metabolic health, then do some HIIT and “burn baby, burn!”.

References

Arney, B. E., Foster, C., & Porcari, J. (2019). EPOC: IS IT REAL? DOES IT MATTER?. ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal, 23(4), 9-13.

Baker, J. S., McCormick, M. C., & Robergs, R. A. (2010). Interaction among Skeletal Muscle Metabolic Energy Systems during Intense Exercise. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2010, 905612. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/905612

Baechle, Thomas R., and Roger W. Earle, eds. Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Human Kinetics, 2008.

Clark, M. A., Lucett, S., & Corn, R. J. (2008). NASM essentials of personal fitness training. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Falcone PH, Tai CY, Carson LR, Joy JM, Mosman MM, McCann TR, Crona KP, Kim MP, Moon JR. Caloric expenditure of aerobic, resistance, or combined high-intensity interval training using a hydraulic resistance system in healthy men. J Strength Cond Res. 2015 Mar;29(3):779-85. DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000661. PMID: 25162652.

Foureaux, G., Pinto, K. M. D. C., & Dâmaso, A. (2006). Effects of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and resting metabolic rate in energetic cost. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 12(6), 393-8.

Gupta, R. D., Ramachandran, R., Venkatesan, P., Anoop, S., Joseph, M., & Thomas, N. (2017). Indirect Calorimetry: From Bench to Bedside. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 21(4), 594–599. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijem.IJEM_484_16

Jelleyman C, Yates T, O'Donovan G, Gray LJ, King JA, Khunti K, Davies MJ. The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015 Nov;16(11):942-61. DOI: 10.1111/obr.12317. PMID: 26481101.

O'Keefe, J. H., O'Keefe, E. L., & Lavie, C. J. (2018). The Goldilocks Zone for Exercise: Not Too Little, Not Too Much. Missouri medicine, 115(2), 98–105.

Osawa Y, Azuma K, Tabata S, Katsukawa F, Ishida H, Oguma Y, Kawai T, Itoh H, Okuda S, Matsumoto H. Effects of 16-week high-intensity interval training using upper and lower body ergometers on aerobic fitness and morphological changes in healthy men: a preliminary study. Open Access J Sports Med. 2014 Nov 4;5:257-65. DOI: 10.2147/OAJSM.S68932. PMID: 25395872; PMCID: PMC4226445.

Paoli, A., Moro, T., Marcolin, G. et al. High-Intensity Interval Resistance Training (HIRT) influences resting energy expenditure and respiratory ratio in non-dieting individuals. J Transl Med 10, 237 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-10-237

Sijie T, Hainan Y, Fengying Y, Jianxiong W. High intensity interval exercise training in overweight young women. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2012 Jun;52(3):255-62. PMID: 22648463.

Skutnik BC, Smith JR, Johnson AM, Kurti SP, Harms CA. The Effect of Low Volume Interval Training on Resting Blood Pressure in Pre-hypertensive Subjects: A Preliminary Study. Phys Sportsmed. 2016;44(2):177-83. DOI: 10.1080/00913847.2016.1159501. Epub 2016 Mar 17. PMID: 26918846.

Villegas, J. G. (2020). Use of heart rate variability in biomedical training control. J Cardiovasc Med Cardiol, 7(3), 208-212.

Wingfield HL, Smith-Ryan AE, Melvin MN, Roelofs EJ, Trexler ET, Hackney AC, Weaver MA, Ryan ED. The acute effect of exercise modality and nutrition manipulations on post-exercise resting energy expenditure and respiratory exchange ratio in women: a randomized trial. Sports Med Open. 2015 Dec;1(1):11. DOI: 10.1186/s40798-015-0010-3. Epub 2015 Jun 5. PMID: 27747847.