You have to be able to start, stop and control the motion - that's why deceleration training is a vital component of fitness programming and any strength and conditioning program.

Creating a performance-based conditioning program can be akin to building a car when it comes to what you need the car to do. Most people consider a car solely as a vehicle to get from point A to B. As much as this is true, you also want a car that can move efficiently to get you to where you’re going and, importantly, be able to stop when you get there.

Exercise programs need to also do the same when it comes to how we challenge the body. Starting motion may not be an issue for most, it’s how we slow down mass and momentum that becomes the problem when there’s an imbalance in the exercise plan.

If you have not yet become a strength and conditioning specialist, be sure to check out our program bundle that will give you the tools to successfully apply modalities like deceleration training.

two ways to view deceleration training

There are a couple of ways to view deceleration when it comes to movement. One way is to look at it as the eccentric lengthening of the muscle. This is the point during the muscle contraction spectrum that precedes the concentric shortening. It’s the transition or amortization phase between the eccentric and the concentric where the muscle transforms energy from the lengthened and energy “loaded” position to the quickly shortened “explosive” contraction. The other way to look at deceleration is the actual slowing of motion, as in the slowing of the arm as it releases a ball in a throw. It has to slow down and stop after all the effort to speed the arm through the throwing motion. In both of these examples of deceleration, the inability to slow down efficiently is where excess joint stress can occur and may eventually lead to increased opportunity for injury.

To consider how important deceleration is to the body you don’t have to look further than our anatomy. The direction of the fibers of the gluteus maximus run in an oblique direction, down and away from the the iliac crest and sacrum as it connects to the femur and the IT band. This structure helps serve as the braking system as it works with the rest of the glute complex, hamstrings, etc., to decelerate the body when that same leg hits the ground as it continues to the next phase of the gait cycle. Specifically it’ll decelerate hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Having control in all these motions is crucial for hip, knee and ankle integrity not just when it comes to running but any movement that requires a rapid change of direction.

You can also look beyond structure and observe synergies that are assembled or work together for deceleration. One example is the shoulder rotator cuff which is made up of the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and the teres minor. Location of the muscles alone situates these four muscles so that there is one anterior with three posterior. If the term “safety in numbers” can be applied to human anatomy this is it, especially when you consider what is required at the rotator cuff to throw at a target or more typically hold, carry, or move something in front of you.

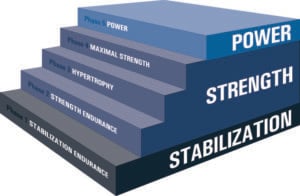

Exercises that strengthen the hips (i.e., glute bridges) and exercises that strengthen the rotator cuff (i.e., shoulder scaptions) are typically seen in the rehabilitation environment. If it’s effective enough to use these types of exercise under slow tempos and light intensities to rehabilitate an injured area, then it’s worth strong consideration for stability level training in a deconditioned client or athlete that has shown weakness in their ability to control deceleration. Once the client can better eccentrically load a given area they will be better able to concentrically unload/explode the body into different directions or motions with better managed stresses on the joints.

The fitness professionals role is to create a plan or strategy that addresses the “brakes” before the “engine” is built. The best starting point for this is to do an assessment to identify muscle imbalances. By identifying these first, the fitness professional can remove the road blocks that can get in the way of using the muscular system efficiently. Once this is done, the programming can begin with exercise and intensity selections applicable to the assessment results. You can use the NASM Edge app to track the results of the assessment, and you will also receive recommended corrective exercise. Novice or deconditioned clients will most likely need stability level training. Even highly conditioned athletes are candidates for stability and deceleration-centric training.

Here are some programming examples that can address conditioning for deceleration.

Stabilization Endurance (OPT Phase 1) Upper Body

- SMR - Hold until decrease in tension ~ 30-60 seconds

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Pectoralis Major

- Stretch (Static) - Hold 30 seconds, 1-2 sets

- Quadruped Lat Stretch with Ball

- Standing, Wall Pec Stretch

- Activation - 6-10 reps per side, slow 4/2/1 tempo, 1-2 sets

- Single Leg, Single Arm Cobra - with light weights

- Balance - 30 seconds each leg, 1-2 sets

- Single Leg Balance with Bodyblade® (or opposite arm forward reach)

- Reactive - 10 repetitions

- Throw with Hold (Perform throwing with a light ball but do not let go)

Strength Endurance (OPT Phase 2) Lower Body

- SMR - Hold until decrease in tension ~ 30-60 seconds

- Adductors

- TFL

- Stretch - (Active-Isolated) 10 reps, hold each for 1-2 seconds, 1-2 sets

- Standing Adductor Stretch

- Standing Hip Flexor with Overhead Arm Reach

- Activation - 10 reps, moderate speed, 2 sets

- Ball Bridge

- Balance - 8 reps, per side, 2 sets

- Single Leg Squat Touchdown to Scaption

- Reactive - 10 reps, 2 sets

- Repeat Lateral Jump Squat

Deceleration Specific Exercises

- Drop and Catch (light SandBell® with hands chin high, quickly lower hips to catch SandBell keeping hands at chin height)

- Lateral Single Leg Hop and Balance Hold

- Speed Ladder: Sample pattern

- Lateral In-In-Out with Balance (balance on outer foot after both feet have transitioned through the speed ladder box)

- Single Leg Hops (same leg) Zig-Zag Pattern with balance and hold when foot is outside ladder rungs

- Balance with Medicine Ball (MB) Catch to Opposite Hip with Stabilization

The ability to control deceleration is needed by more than just athletes that throw or perform agility-type movements on the competitive field. It’s a move that we all rely on in one way or another in our everyday lives. Consider a person who’s forgotten something and had to do a 180 degree turn – stopping in their tracks, pivoting around and re-accelerating back to where they came from. Yes, they just eccentrically decelerated, stabilized as they turned and concentrically accelerated in the opposite direction. This required the “brakes” to engage before the engine. Athlete or not, an athletic move was just done.

When looking at the workout and components that need to be considered, one of the things to examine is can the muscles and motions be properly loaded before they are unloaded. Having the speed of a Ferrari engine may be great, but if you have the brakes of a Yugo, you’re only able to safely tap into part of that car’s potential.

Track your clients’ progress against performance enhancement goals by utilizing the Goal and Milestone feature of NASM Edge. You can also track and compare cardio, endurance, and strength performance assessments, as well as access an exercise library.