NASM Corrective Exercise Specialists (CES) can provide targeted help to improve their client’s baseline physical health before surgical intervention. The purpose of prehabilitation is to put the client into the best position possible for post-procedure recovery.

Let's dive into the specifics of how prehabilitation can safely and effectively prepare your clients for surgery.

What is prehabilitation?

Prehabilitation, or “prehab,” refers to corrective exercise programming meant to reduce the risk of non/indirect contact musculoskeletal or overuse injury. This is often employed as a proactive approach to strength, stability, balance, and mobility in preparation for a surgery or other medical intervention. This article will focus on pre-surgical prehabilitation.

The general idea behind prehabilitation is “better in, better out,” as in the better condition the client goes into surgery, the better they will be after surgery.

Durrand et al. (2019) suggested the ideal prehabilitation program would be comprehensive and integrate interventions based on a patient's needs, which may include nutrition guidance from a registered dietitian, behavioral therapy from a licensed mental health provider, and exercise programming from a physical therapist or corrective exercise specialist.

common prehab procedures for clients

Prehabilitation is appropriate in circumstances that may require preparation for surgical procedures and other taxing medical treatments.

Some of the more common procedures include:

- Cardiac surgeries.

- Cancer treatments.

- Orthopedic surgeries, such as ACL repair and total joint replacement.

* note about cancer procedures

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United States averages 1.8 million cancer diagnoses per year, many requiring extensive treatment, often surgical.

Prehabilitation for cancer is defined as interventions occurring after diagnosis but before acute care (Meneses-Echavez et al., 2020).

The Goal of Prehabilitation

The goal of prehabilitation remains mostly the same for all medical interventions, although the exact goal will vary by client.

Mina et al. (2015) suggested that with the intention of facilitating postoperative recovery, prehabilitation would have significant positive effects for both the client and healthcare costs associated with an otherwise lengthy and intensive recovery process.

Additionally, prehabilitation programs have been shown to improve postoperative quality of life for those undergoing cancer treatments (Chou et al., 2018).

Joint Replacement Surgery

For NASM Corrective Exercise Specialists, one of the more common interactions will be with clients needing prehabilitation programming for joint replacement surgery.

According to Foran (2020), the most common total joint replacement surgery performed is total knee arthroscopy (TKA), with nearly 800,000 surgeries performed each year in the United States. These surgeries are usually a result of the most common joint disease in the world, osteoarthritis.

A study by Jahic et al. (2018) suggested a targeted physical prehabilitation program lasting six weeks before surgery showed post-operative benefits for up to six months. Prehabilitation programs have shown to improve postoperative joint range of motion and strength recovery (Calatayud et al., 2017).

Depending on the patient’s needs, the guiding physician may recommend a specific prehabilitation plan and refer them to a specialist. Still, if the need is general and the risk factors relatively low, the physician may leave it up to the patient to find a CES to help them with their prehabilitation needs.

Important point:

If an individual seeks you out for their prehabilitation needs, it is crucial to receive clearance for physical activity from their guiding physician or surgeon and be aware of specific contraindications that may pertain to physical activity as each patient undergoing surgery will have varying needs.

Additionally, a thorough health screening and Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) may help identify potential contraindications that would require further clearance or direction from their guiding physician.

The Role and Responsibility of the Corrective Exercise Specialist

It is critical that the CES recognizes that they are only one member of a larger team working together to provide the best post-surgical outcome for the client.

According to Tew et al. (2018), preoperative exercise training should be part of a more extensive multi-modal prehabilitation program.

Get a physician's clearance

During the consultation, the fitness profession should seek a physician’s clearance for exercise along with recommended limitations and specific contraindications for the client.

The consultation is also the perfect time to learn about the client’s circle of care. It is not unusual for a client seeking prehabilitation to be working with physical therapists, dietitians, and other allied health practitioners while seeking additional exercise activity with a certified trainer.

Learn the allied healthcare professionals involved

Knowing whether a client is working with other allied healthcare professionals helps determine whether additional referrals are necessary and adds some clarity to the trainer's role as a supporting member of the larger team.

For instance, if a client is already receiving guidance from a dietitian, it may help to know nutrition questions can be referred to their dietitian. Additional support can be provided to assist the client in adhering to the dietitian's program.

Check to See If a Client is Using a Physical Therapist

Additionally, if a client is working with a physical therapist, the trainer may have to adapt their programming to recover properly between physical therapy appointments and training appointments.

When possible, it is best to reach out either directly or through the client to clarify the physical therapist and dietitian's objectives, seeking clarity when necessary to ensure a synergistic relationship for both the client's safety and optimal prehabilitation outcomes.

When a CES demonstrates a willingness to communicate and be a team player, the odds of getting future referrals increase as a bonus to the client's satisfaction.

Obtaining a Physician's Clearance and Guidance

Sometimes clients will seek out a CES’s help for prehabilitation, even though they have yet to get a referral from their guiding physician. Depending on the results of the health screening and PAR-Q+, additional guidance may not be necessary.

However, if there are any red flags, such as chronic diseases, acute pain or painful movement, or signs of injury, physician's clearance is highly recommended as the client's needs may be beyond the scope of a CES to assess and manage. For prehabilitation, additional guidance from the client's physician is critical to the safety of the client.

A thorough assessment by the guiding physician would include specific contraindications to exercise that will be critical for the CES to know. It is also crucial to understand all current treatments, medications, ongoing investigations, prior and current physical activity levels, and, ideally, assess functional capacity and quality of life (Tew et al., 2018).

As the client progresses, a re-evaluation by the client’s physician may also be warranted if pain or other symptoms appear or worsen once the client begins their prehabilitation program.

specific objectives on a case-by-case basis

Depending on the medical procedure a client is preparing to undergo, there may be specific objectives that need to be met to ensure an optimal outcome.

For instance, according to Calatayud et al. (2017), maintaining quadriceps strength leading up to a TKA improves recovery time and facilitates a return to baseline range of motion post-surgery.

Another example of a specific objective to improve recovery and quality of life is of cardiorespiratory objectives and muscle strength maintenance in preparation for cancer treatments (Chou et al., 2018).

Taking the time to understand what the medical procedure the client is about to undergo will entail as well as the acute rehabilitation process will look like after surgery can also be incredibly beneficial. This type of information is critical when making program considerations and prioritizing goals with the prehabilitation client.

Utilizing the Corrective Exercise Continuum

Most clients seeking prehabilitation services would likely present a variety of postural dysfunctions and movement compensations.

Considering the notion of "better in, better out," it is reasonable to think a client going into surgery with postural dysfunction and movement compensations would likely come out of surgery with them as well.

It is also common for clients to rely on tools such as canes, crutches, walkers, and other mobility aids, which can create additional overuse patterns that may also need to be addressed.

The NASM approach to corrective exercise is a systematic process that identifies the problem, solves the problem, and then implements the solution.

Identifying the Problem

The CES has many assessments at their disposal, such as static, transitional, and dynamic postural assessments, as well as joint mobility assessments to help them identify the problem.

Utilizing transitional movement assessments like the overhead squat assessment will provide insight as to which muscles are overactive and will need to be inhibited and/or lengthened, and which muscles will need strengthening.

Some clients may not be able to perform a squat due to contraindications or reliance on mobility aids making joint mobility assessments a more reliable alternative. Combine this information with the objectives set by the guiding physician, and a program will begin to form.

Solving the Problem

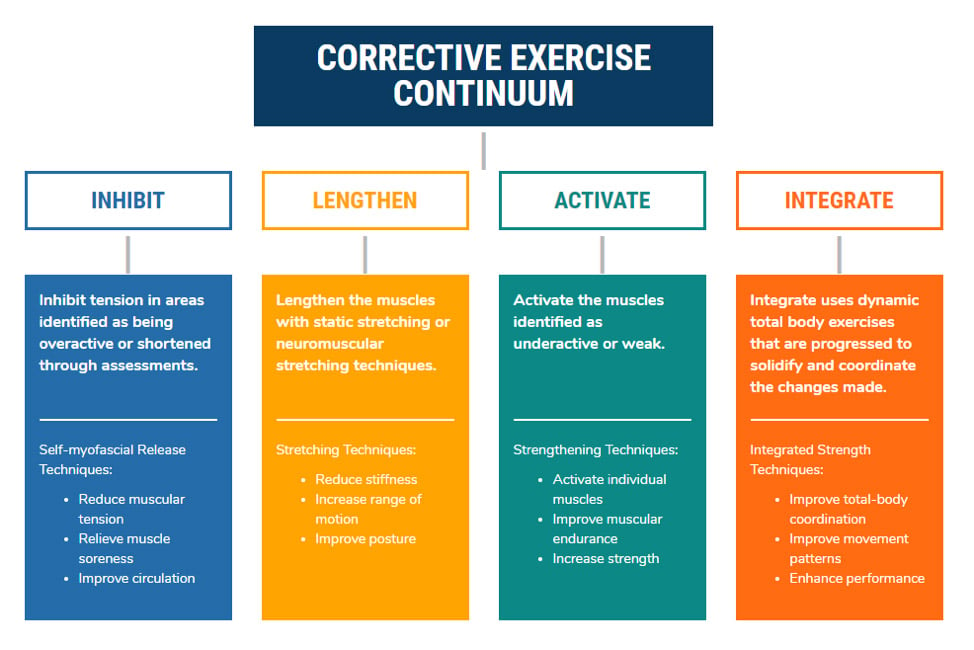

Solving the problem pertains to the design process of the corrective exercise process. The corrective exercise program will have four phases that make up the Corrective Exercise Continuum:

- Inhibit.

- Lengthen.

- Activate.

- Integrate.

The Lengthen phase includes the stretching techniques necessary to increase tissue extensibility, length, and range of motion.

The Activation phase is used to increase reeducate or improve the activation of underactive tissues. The client’s assessment results will guide which muscles will require inhibiting/lengthening and activation.

The final phase, Integration, includes techniques that are used to retrain the collective synergistic function of the entire muscular system through functionally progressive movements. In the case of the TKA prehabilitation plan, specific goals such as quadriceps strength and lower limb stability can guide exercise selection for the integration phase of the continuum.

Regular reassessment of movement and mobility is a great way to track improvements in strength and stability. Tracking program variables such as intensity and exercise progressions are also great methods for measuring progress.

Implementing the Solution

The last phase of the corrective exercise process is the implementation of the solution developed during the second phase. Implementation includes the coaching of the selected techniques, cueing, and management of the programmed solution.

Implementation of the solution for prehabilitation may last up to six weeks prior to the client’s procedure.

Summary

Prehabilitation is becoming more widely recognized as something a client should do before medical treatment when possible to improve post-surgical recovery and reduce the length of time necessary for rehabilitation.

The CES can play a significant role in optimizing a client’s movement quality, strength, stability, balance, and mobility in preparation for a surgery or other medical intervention. Using the corrective exercise process, the CES can systematically identify neuromusculoskeletal dysfunction, develop a plan of action, and implement an integrated corrective strategy.

As part of the continuum of care, it is critical the Corrective Exercise Specialist follows direction from the guiding physician as there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all program—even for the same medical procedure—as each client’s needs will vary.

References

Calatayud, J., Casana, J., Ezzatvar, Y., Jakobsen, M. D., Sundstrup, E., & Andersen, L. L. (2017). High-intensity preoperative training improves physical and functional recovery in the early post-operative periods after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 25, 2864-2872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-3985-5

Chou, Y., Kuo, H., & Shun, S. (2018). Cancer prehabilitation programs and their effects on quality of life. Oncology Nursing Forum, 45(6), 726-736. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.onf.726-736

Clark, M., Lucett, S., & Sutton, B. G. (2014). NASM essentials of corrective exercise training. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Durrand, J., Singh, S. J., & Danjoux, G. (2019). Prehabilitation. Clinical Medicine, 19(6), 458-464.

Foran, J. R. H. (2020). Total Knee Replacement. OrthoInfo. Retrieved on September 16, 2020 from https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement

Jahic, D., Omerovic, D., Tanovic, A. T., Dzankovic, F., & Campara, M. T. (2018). The effect of prehabilitation on post-operative outcome in patients following primary total knee arthroplasty. Med Arch, 72(6), 439-443. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2018.72.439-443

Meneses-Echavez, J. F., Loaiza-Betancur, A. F., Diaz-Lopez, V., & Echavarria-Rodriguez, A. M. (2020). Prehabilitation programs for cancer patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials (protocol). Systematic Reviews, 9(34), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-1282-3

Mina, D. S., Scheede-Bergdahl, C., Gillis, C., & Carli, F. (2015). Optimization of surgical outcomes with prehabilitation. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 40, 966-969. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0084

Tew, G. A., Ayyash, R., Durrand, J., & Danjoux, G. R. (2018). Clinical guidelines and recommendations on preoperative exercise training in patients awaiting major non-cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia, 73, 750-768. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14177