Originally appeared in the fall 2016 issue of American Fitness Magazine

Many clients view osteoporosis as a concern among seniors. As fitness professionals, though, we know that building peak bone mass begins early in life and ends before we reach middle age.

We also know how proper exercise and nutrition can strengthen clients’ skeletal system. Personal trainers work hard to design programs that help clients achieve their goals. By including bone health in our program design and nutrition discussions—even for our healthiest young clients—personal trainers can contribute to the prevention of osteoporosis on a large scale.

To earn 0.2 AFAA/0.2 NASM CEUs, purchase the CEU quiz ($35) and successfully complete it online at www.afaa.com.

This article will demonstrate how to help all clients achieve peak bone mass, maintain bone mass and recognize risk factors of osteoporosis. You will also learn how to keep clients with osteoporosis safe, while helping them with bone-beneficial exercise and nutrition.

Youth: Building Peak Bone Mass

Humans have a limited amount of time to achieve peak bone mass. That window opens in puberty and closes in the mid-20s, or in some cases in the third decade of life. (1, 2)

In childhood and adolescence, the primary objective for bone health is to attain the genetic potential of peak bone mass. (1) To do this, we have to ensure proper nutrition and exercise to build the strongest bones possible. It’s the only chance we will get.

Youth Nutrition and Bone Health

Three main dietary nutrients contribute to optimal bone density: calcium, vitamin D and protein. In the literature, there is a concern about “milk displacement” among our youth, in which soda, sports drinks and energy drinks are replacing milk consumption. (2,5,6)

This contributes to childhood obesity and affects bone health. It is important for children to consume foods that supply calcium, vitamin D and protein before they consume foods and drinks that provide little nutritional value. (1)

Calcium. For children aged 9 to 18, the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for calcium is 1,300 mg per day, which is roughly four servings of dairy. (1) The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that diet, not supplements, should be the primary source for calcium. This is both because supplements have a reduced bioavailability and because this promotes healthy lifelong dietary habits. (2) A few notes about calcium:

- Dairy products. Researchers have stated that dairy is the optimal source from which to obtain calcium. Milk also provides protein, vitamin D and other nutrients such as magnesium and phosphorus, all of which are important for bone health. (1)

- Vegetables. Oxalates in spinach, collard greens, rhubarb and beans reduce the bioavailability of the calcium found in vegetables. Also, it is difficult to eat a large enough quantity of vegetables to meet the RDA for calcium with vegetables alone. (1)

- Soy milk. A study looking at supplementation in soy milk shows that the calcium might have reduced bioavailability. (3)

Vitamin D. Also called calciferol, vitamin D is actually a hormone responsible for the absorption and utilization of calcium. (1) The RDA for vitamin D is 600 IU or 15 mcg per day for both males and females aged 1 to 70 years. (4) Vitamin D is found in fortified dairy products, egg yolk, fatty fish and fortified orange juice. (4)

Vitamin D is also synthesized by our skin when it is exposed to sunlight; in fact, that’s our primary source of the nutrient. Because children are spending more time indoors and using sunscreen when outside, vitamin D deficiency in youth can be a problem. (1) In a recent commentary in the Journal of the American College of Nutrition, researchers state that moderate, unprotected sun exposure (less time than is required to burn) should be “sought rather than avoided.” (8)

Protein. This nutrient provides the amino acids to build the bone matrix. It also stimulates insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which is an important player in bone formation. (2) According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the protein Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for males and females aged 9 to 13 years is 0.76 g/kg/d. At ages 14 to 18 years, this decreases to 0.73 and 0.71 g/kg/d for males and females, respectively. (19)

BUILD YOUR BONE HEALTH VOCABULARY

As we talk about exercise and bone health, you’ll notice a few different terms being used.

Bone mineral density (BMD) describes the amount of calcium and other minerals that are found in an area of bone. This can be measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

Bone strength refers to the geometry of the bone, and how it may absorb and withstand various forces. It includes such factors as the shape of the bone, its size, and its microarchitecture. Measurement of bone geometry is very complex, and it is usually accomplished with quantitative computed tomography or high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging.

Conclusion: Both BMD and bone geometry are important for strong, healthy bones. A very dense bone without good geometry will not be able to bend and absorb forces.

Youth Exercise and Bone Health

Youth exercise can have a profound effect on the achievement of peak bone mass. The type of exercise a young person does is very important.

Research has shown that children who participate in high-impact sports (gymnastics, volleyball) and odd-impact sports (basketball, soccer) generally have higher bone mineral density (BMD) and improved bone geometry. (7)

One randomized controlled trial, coupled with a summary from the American Academy of Pediatrics, shows that healthy children who participated in high-impact, low-frequency exercises such as jumping, hopping or skipping for 10 minutes three times per week increased BMD of the femoral neck. (9,2) The American Academy of Pediatrics goes on to say that weight-bearing activities (such as dancing, jogging, jumping and walking) are preferred over swimming and cycling for pediatric bone health.

There does, however, seem to be a limit as to how much activity a child’s bones can take. In a study of 6,000 high school girls, those who participated in more than 8 hours of impact sports per week (such as basketball, cheerleading, gymnastics or running) were two times as likely to sustain a stress fracture. (1,10)

Adulthood: A Bone Maintenance Plan

From our 20s to our 60s (for most adults), our goal is to maintain the bone density we achieved in childhood and adolescence. (2) Here, nutrition and exercise are still key, but so is the awareness and mitigation of risk factors that can lead to a reduction in bone mass.

Adult Nutrition and Bone Health

As in childhood, the three most important nutrients for bone health in adulthood are calcium, vitamin D and protein.

Calcium. Adult males aged 19 to 70 years and females aged 19 to 50 years should consume 1,000 mg of calcium per day. Females aged 51 to 70 should consume 1,200 mg of calcium daily. (11)

Vitamin D. Adult males aged 19 to 70 years and females aged 19 to 50 years should consume 600 IU (15 mcg) of vitamin D per day. It should be restated that the primary source of vitamin D is its synthesis by our skin when exposed to sunlight. This exposure should be direct (not blocked by sunscreen) and should be moderate (not lasting long enough to cause a sunburn). Vitamin D may also be consumed in food, but sources are limited to dairy, egg yolk, fatty fish, and fortified orange juice. (4)

Protein. The amino acids in protein are needed to build the bone matrix. Protein also stimulates the production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which aids in bone formation. (2) According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the protein Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for adults aged 19 years and older is 0.66 g/kg/d, except during pregnancy and lactation in women, when it rises to 0.88 g/kg/d and 1.05 g/kg/d, respectively. (19)

Adult Exercise and Bone Health

Research on exercise prescription for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in adults is not as clear as it is regarding children. To date, studies have focused mostly on postmenopausal women, even though others in the same age group are men and premenopausal women. Much of the evidence regarding adult exercise and bone health can seem contradictory if we review one study at a time.

However, if we use this information along with our experience and educated reasoning skills, we can infer that adults need to do both impact exercise and resistance training to maintain and possibly improve BMD. Some evidence points out that exercise may have site-specific (lumbar spine or femoral neck) results. Knowing this, we can choose exercises for our clients based on their needs. Here, some specific study results:

Premenopausal women: Resistance training and high-impact, weight-bearing exercise. One systematic review and a review of the literature from Brazil came to the following similar conclusions. (12,15) With regard to premenopausal women, resistance training exercise and high-impact, weight-bearing exercise—either alone or in combination—can increase BMD in the lumbar spine and femur 1 to 2%. (15) A randomized controlled trial with premenopausal subjects found that a 12-month, progressive high-impact training program (3x/week plus home exercises, with more than 66 sessions total) resulted in enlarged bone circumference and improved bone geometry relating to increased bone strength. The same effects were not found in participants who were less compliant (< 19 sessions). (13)

Postmenopausal women: Resistance training and low-impact activities. This group has been the focus of most research regarding exercise and osteoporosis. In a systematic review, Nikander et al. uncovered mixed results. (15) The general findings were that resistance training can have a positive effect on BMD (1 to 2%) at the lumbar spine, but improvements at the femur were not consistent. They also reported that several studies found no improvement in BMD at the lumbar spine or femur with walking or endurance training programs.

A different meta-analysis revealed that a combination of impact activities was significant for improving BMD at both the lumbar spine and femoral neck. (16) The study looked at high impact (jumping rope, vertical jumps, running more than 9 km/hr), odd impact (aerobics and agility activities), low impact (walking, stair climbing, and jogging at less than 9 km/hr or 11 min/mile) and combined impact (“impact activity mixed with high-magnitude joint reaction force loading through resistance training”). (6)

The authors concluded that low-impact activities (jogging, stair climbing, walking) when combined with resistance training are the most effective in maintaining BMD. Interestingly, this study found that high- and odd-impact activities did not have an effect on BMD in postmenopausal women.

Men aged >31: Site-specific exercise. There is little evidence specifically regarding males, exercise and osteoporosis. A meta-analysis found that site-specific exercise may help improve BMD for men older than 31 years. (14) Overall, more research is necessary to determine the most beneficial exercise for men and bone health. (14,15)

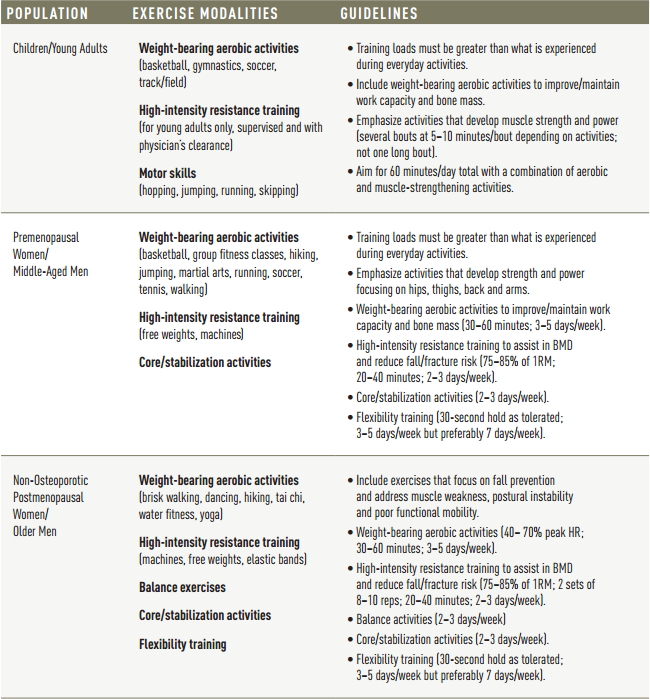

EXERCISE GUIDELINES FOR BONE HEALTH

Use this reference to select bone-building activities for clients in various age groups. In all cases, it is very important for the client to obtain a written clearance from their physician prior to participation. This is as vital for young adults and children (particularly with regard to resistance training) as it is for older adults, who may have risk factors for cardiovascular disease or other conditions or medications that need to be considered. (23–29)

Understanding Osteoporosis

According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), osteoporosis is a silent condition and the most common bone disease in humans. Its characteristics are low bone mass and a disturbed bone architecture, with deteriorated bone tissue jeopardizing bone strength and increasing fracture risk. (17)

Testing. Osteoporosis is detected by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). One of the results is reported as a T-score, which compares the patient’s bone mineral density (BMD) to “young normal” adults of the same gender. (17) A T-score of less than -1.0 results in a diagnosis of osteopenia (early-stage osteoporosis)2 and a T-score of less than or equal to -2.5 indicates osteoporosis. (17)

Categories. There are two categories of osteoporosis: primary and secondary. Primary osteoporosis is bone deterioration due to age and/or decreased gonad function. Secondary osteoporosis is a result of chronic illness that causes accelerated bone loss. (18)

Causes. While primary osteoporosis is related to age and hormone levels, secondary osteoporosis has several causes. Some of the most common are:

- Endocrine and metabolic illness such as anorexia nervosa, athletic amenorrhea, diabetes mellitus (type 1) and hyperparathyroidism.

- Genetic disorders including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome and osteogenesis imperfecta.

- Medications such as glucocorticoids (steroids to reduce inflammation), excess thyroid hormone, methotrexate (for rheumatoid arthritis) and the blood thinner heparin (with prolonged use).

- Nutritional problems such as alcoholism, chronic liver disease, deficiencies of calcium and/or vitamin D, gastric operations and malabsorption syndromes. (18)

- The female athlete triad, which is described as low energy intake (with or without an eating disorder), menstrual dysfunction and low BMD. (See Female Athlete Triad callout at end of article.)

Recognizing At-Risk Clients

Dr. Jeannette South-Paul’s article in American Family Physician gives a comprehensive list of risk factors for osteoporosis: female gender, petite body frame, low body weight, white or Asian ancestry, sedentary lifestyle or history of immobilization, null parity, increasing age, high caffeine intake, renal disease, lifelong low calcium intake, smoking, excess alcohol use, long-term use of certain drugs, impaired calcium absorption, being postmenopausal. (18) It is important to know these risk factors.

However, it may be more useful to create clusters and associations with your clients to effectively identify people at risk. Let’s look at a few examples you may see.

Client 1 is a 15-year-old female who was recently immobilized for an ankle sprain. She is on the high school cross-country team and the swim team. Recently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, she is managing well.

Client 2 is a 56-year-old female who had gastric bypass surgery and is now well enough to start exercising to maintain her new weight loss. We’ll assume she is postmenopausal, and she led a very sedentary lifestyle prior to her surgery.

Client 3 is a 70-year-old male who is a former competitive cyclist but now has a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF). (Hint: People with AF usually take a blood thinner, maybe heparin.) He still cycles but lately he has noticed that he’s getting weaker and loses his balance when he’s working in the garden.

All of these clients appear healthy, energetic and ready for a workout. In recognizing that these people are at risk for osteoporosis or osteopenia, you will want to ask each of them to secure permission from their physician and other members of their healthcare team before you begin working with them. As an astute fitness professional, you realize your role can have a positive impact in both their fitness and bone health.

The following sections will relate back to these client examples and highlight what they may experience with their doctors, as well as ways in which you can help them. (17)

Understanding the Screening Process

First it is important to understand what is advised in regard to screening. We’ll look to the NOF for these recommendations. (17) Remember, Client 2 is at risk because of her prior sedentary lifestyle and her gastric bypass surgery. Client 3 is at risk because of his age, his background in cycling and his decreased balance.

Clients 2 and 3 should have a DXA scan for BMD, since they fit the description for two of the recommendations: 1) “In women age 65 and older and men age 70 and older, recommend bone mineral density (BMD) testing” and 2) “In postmenopausal women and men age 50 to 69, recommend BMD testing when you have concern based on their risk factor profile.”

Clients 2 and 3 are thankful for your advice and see their doctors. When they return with their BMD results, Client 2 reports she has osteopenia (early-stage osteoporosis) and Client 3 has osteoporosis. Client 3 has been prescribed medication to help improve his bone density. To learn what he might be taking, read “Bone-Building Medications”.

Client 1 is a very different matter. The first line of treatment for adolescents focuses on nutrition, not medication. What’s more, your concern for her will be in helping her achieve peak bone mass, which is especially important since she is at increased risk for osteoporosis.

Designing a Program for Clients with Osteoporosis

The literature has shown that the most effective exercise for improving BMD in adults is a combination of resistance training and impact or agility training.12 The question is: What is safe?

Special considerations for clients with osteoporosis. A team of fitness and healthcare providers should develop a progressive exercise program for those diagnosed with osteoporosis due to the following: (26,29)

- People with osteoporosis have heightened fear and anxiety of falling.

- People with severe osteoporosis are at a higher risk of fracture in the wrists, spine, hips, thighs and ankles if performing more vigorous impact-oriented exercises.

- Neuromuscular function, such as balance, should be assessed prior to exercise.

- Assessing mobility-related fitness parameters (strength and flexibility of the upper and lower body, aerobic endurance, agility and balance) in older adults is recommended.

Exercises to avoid. For all degrees of osteoporosis, research recommends avoidance of jumping activities and all exercises that involve deep forward trunk flexion or spinal flexion (e.g., full sit-ups, rowing, toe touches).

Biomechanically speaking, spinal flexion exercises and flexion-based functional movements increase the risk of fracture in the vertebral body. Along those lines, if your client cannot properly hip-hinge during a squat and shows increased spinal versus hip flexion, they should not be doing a squat until they can maintain a neutral spine position. With any exercise prescription, your client needs to be safe from a stability standpoint, as most hip fractures happen as a result of a fall.

Site-specific exercises. If your client has had a DXA scan and can tell you that his bone density is decreased in a specific site (usually the hip or lumbar spine), you may design exercises to stimulate site-specific bone formation. Some examples for the lumbar spine include planks and spinal extension exercises.

Spine Extension

Examples for the hip are multidirectional lunges, double- or single-leg dead lifts, or leg press.

Examples for the hip are multidirectional lunges, double- or single-leg dead lifts, or leg press.

Dead Lift

Aerobic exercise. Walking can have a positive effect on BMD at the femur, but not the spine. High-impact aerobics have the greatest effect on both femur and spine BMD.

Resistance training. It is important to strengthen the back extensor muscles for both improved spine BMD and reduced fall risk.

Bird Dog on Ball 2

One study describes that postmenopausal women will maintain or improve hip BMD if they participate in resistance training at 70 to 90% of 1RM, three to four sets of 8 to 12 repetitions, two to three times per week over the course of 1 year. (20)

See how to do a normal bird dog here.

Putting It All Together

Let’s get back to our clients. As you recall, Client 1 is a teenage girl, recently immobilized by an ankle sprain. Her sports are cross-country and swimming. Your role as her personal trainer must include helping her to achieve peak bone mass. You are concerned because her cross-country sport, gender, recent immobilization and diagnosis of type 1 diabetes are all risk factors for having low BMD in the future.

Nutritional discussions must include calcium, vitamin D and protein intake. Exercise design for this athlete should involve cross-training that incorporates high-impact and odd-impact activities, such as dancing and skipping. Since she is a runner, functional training exercises that target the hip and core—such as resisted or weighted chops in a split stance position—will be both beneficial and meaningful to her.

Chop

Client 2 wishes to reverse the effects of her sedentary lifestyle, which has resulted in osteopenia. Since she has had gastric bypass surgery, you educate her regarding DRI values for calcium, vitamin D and protein, and you encourage her to speak to her GI specialist, since her absorption of these nutrients may be altered. As you evaluate her posture, you notice her head and shoulders are forward, and she has difficulty balancing on one foot.

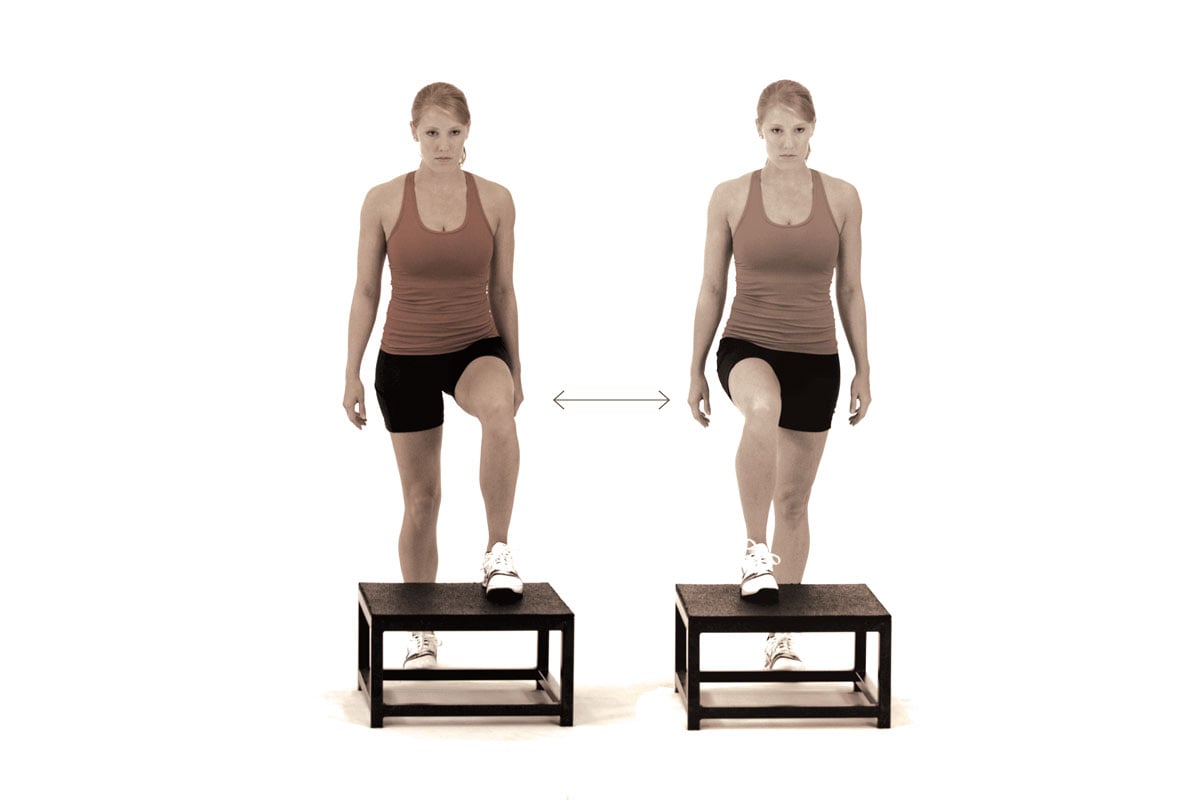

Your exercise design will include back extensor and scapular exercises to improve her posture, and hip strengthening exercises with a balance component to them.

Squat With Row

After six weeks of working together, her posture and balance have improved so much you feel her exercise program can reach its full potential by adding in impact activities such as rapid stair stepping and jump rope.

Rapid Stair Step

She also joins an aerobics class at your encouragement for more odd-impact activity.

Client 3 is an accomplished athlete, but he is a bit depressed with his diagnosis of osteoporosis. Luckily, you know that high-intensity resistance training, balance and proprioceptive exercises, as well as impact activities are safe for him as long as his spine is in neutral and he is safe from falling.

Lunge

You start by retraining his squat mechanics and work on flexibility so he can maintain his posture. After a few weeks of this, he tells you that his balance when gardening is steadily improving. You’re able to progress his program by adding planks, single-leg dead lifts and multidirectional lunges, first without resistance and in a few weeks adding a resistance component to ensure increased BMD.

Conclusion

Developing our bones is a lifelong venture, but the most important building comes at a time in our lives when we tend not to think much about it. As fitness professionals we are in a position to give our clients a remarkable gift—bone health for life. So whether you’re working with a high school athlete, a professional elite, or someone’s dear grandmother, consider the needs of their bones. By helping them understand the consequences of their dietary and activity choices, you will impact their strength for life.

THE FEMALE ATHLETE TRIAD

The female athlete triad is among the causes of secondary osteoporosis, the type of bone loss not related to aging and the hormonal changes that accompany it. As mentioned in this article, the female athlete triad is described as low energy intake (with or without an eating disorder), menstrual dysfunction and low bone mineral density (BMD).

Low energy intake. This includes a spectrum of people, ranging from athletes who unintentionally consume too little to those with an eating disorder (who intentionally reduce caloric intake). (1) Athletes at risk for low energy intake include those who restrict food intake or certain types of food, vegetarians, and those who exercise for prolonged periods. (22)

Menstrual dysfunction. When an athlete becomes amenorrheic, she loses the bone-building effects of estrogen. (21)

Low BMD. Amenorrhea and low body weight, as from an eating disorder, result in a decline in BMD. (21) It can take years for BMD to recover, even after a person is in recovery from an eating disorder and has achieved a normal body weight. (18)

Conclusion: In 2007, the American College of Sports Medicine issued a position statement on the female athlete triad. (22) They recommend that the athlete be treated by a team that includes a physician, a registered dietitian and, for athletes with an eating disorder, a mental health practitioner. (22)

BONE-BUILDING MEDICATIONS

It’s good to know what drugs your client is taking, and that includes any for the prevention or treatment of osteoporosis. There are five categories of medications available for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: bisphosphonates, calcitonin, estrogen agonist/antagonist, hormone therapy and parathyroid hormone. These are typically used in adults, not children and adolescents, whose first line of treatment is nutrition. (1)

Biphosphonates. These medications, often prescribed for people taking glucocorticoids, include familiar brand names such as Actonel, Boniva, Fosamax and Reclast. Results vary, but these generally reduce the incidence of fracture by about 50% over a three-year period. Side effects include difficulty swallowing, gastric ulcers and visual disturbances. (17)

Calcitonin is FDA-approved for the treatment of osteoporosis in women who are at least five years postmenopausal. It is administered daily as a nasal spray, with side effects including rhinitis and nosebleeds.

Estrogen agonist/antagonists. Evista (raloxifene) is FDA-approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. It reduces vertebral fractures by 30% in people who have had a fracture, and by 55% in people who have not had a fracture over three years. Raloxifene also reduces the risk of invasive breast cancer, but it can increase hot flashes and raise the risk of deep vein thrombosis. (17)

Hormone therapy or estrogen therapy is FDA-approved for the prevention of osteoporosis and relief of other symptoms associated with menopause. Vertebral and hip fracture risk can be reduced by 34%, and other osteoporotic fracture risk is reduced by 23%. Since these therapies may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and breast cancer in some people, the FDA says that they should not be the first approach to preventing osteoporosis. (17)

Interestingly, adolescent girls with amenorrhea due to anorexia nervosa or the female athlete triad (see sidebar on page 29) are often prescribed oral contraceptives to improve BMD; however there is no research to support this. Additionally, this treatment may start a menstrual cycle in females with anorexia, which can be incorrectly interpreted as a sign that they have achieved a healthy body weight. (1)

Parathyroid hormone, or teriparatide, is used for treating osteoporosis in men and women with high fracture risk, as well as men with primary osteoporosis. This is an anabolic (bone-building) treatment and should not be used for more than two years. After 18 months of therapy, patients with osteoporosis experienced a 65% decrease in the risk of vertebral fractures and a 53% decrease in non-vertebral fractures. (17)

REFERENCES:

- GOLDEN, N.H. AND ABRAMS, S.A. AND COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION. “OPTIMIZING BONE HEALTH IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS.” PEDIATRICS, 34, NO. 4 (OCT 2014): E1229-43.

- MITCHELL, P.J., ET AL. “LIFE-COURSE APPROACH TO NUTRITION.” OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL, 26 (2015): 2723-42.

- HEANEY, R.P., ET AL. “BIOAVAILABILITY OF THE

CALCIUM IN FORTIFIED SOY IMITATION MILK, WITH SOME OBSERVATIONS ON METHOD.” THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION, 71, NO. 5 (MAY 2000): 1166-69.

- “VITAMIN D FACT SHEET FOR CONSUMERS.” ODS.OD.NIH.GOV/FACTSHEETS/VITAMIND-HEALTHPROFESSIONAL (ACCESSED MAY 11, 2016).

- COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION AND THE COUNSEL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS. “CLINICAL REPORT—SPORTS DRINKS AND ENERGY DRINKS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: ARE THEY APPROPRIATE?” PEDIATRICS, 127, NO. 6 (MAY 2011) (EPUB). DOI: 10.1542/PEDS.2011-0965.

- VARTANIAN, L.R., SCHWARTZ, M.B. AND BROWNELL, K.D. “EFFECTS OF SOFT DRINK CONSUMPTION ON NUTRITION AND HEALTH: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS.” AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH, 97, NO. 4 (APR 2007): 667-75.

- TENFORDE, A.S. AND FREDERICSON, M. “INFLUENCE OF SPORTS PARTICIPATION ON BONE HEALTH IN THE YOUNG ATHLETE: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE” [ABSTRACT]. PM&R: THE JOURNAL OF INJURY, FUNCTION, AND REHABILITATION, 3, NO. 9 (SEP 2011): 861-67.

- BAGGERLY, C.A., ET AL. “SUNLIGHT AND VITAMIN D: NECESSARY FOR PUBLIC HEALTH.” JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF NUTRITION, 34, NO. 4 (JUL 2015): 359-65.

- PETIT, M.A., ET AL. “A RANDOMIZED SCHOOL-BASED JUMPING INTERVENTION CONFERS SITE AND MATURITY-SPECIFIC BENEFITS ON BONE STRUCTURAL PROPERTIES IN GIRLS: A HIP STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS STUDY.” JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH, 17, NO. 3 (MAR 2012): 363-72.

- FIELD, A.E., ET AL. “PROSPECTIVE STUDY OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND RISK OF DEVELOPING A STRESS FRACTURE AMONG PREADOLESCENT AND ADOLESCENT GIRLS.” ARCHIVES OF PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT MEDICINE, 165, NO. 8 (AUG 2011): 723-28.

- IOM (INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE). DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES FOR CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D. WASHINGTON, DC: THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS, 2001.

- MOREIRA, L.D., ET AL. “PHYSICAL EXERCISE AND OSTEOPOROSIS: EFFECTS OF DIFFERENT TYPES OF EXERCISES ON BONE AND PHYSICAL FUNCTION OF POSTMENOPAUSAL WOMEN.” ARQUIVOS BRASILEIROS DE ENDOCRINOLOGIA E METABOLOGIA, 58, NO. 5 (JUL 2014): 514-22.

- VAINIONPÄÄ, A., ET AL. “EFFECT OF IMPACT EXERCISE AND ITS INTENSITY ON BONE GEOMETRY AT WEIGHT-BEARING TIBIA AND FEMUR” [ABSTRACT]. BONE, 40, NO. 3 (MAR 2007): 604-11.

- KELLEY, G.A., KELLEY, K.S. AND TRAN, Z.V. “EXERCISE AND BONE MINERAL DENSITY IN MEN: A META-ANALYSIS.” JOURNAL OF APPLIED PHYSIOLOGY, 88, NO. 5 (MAY 2000): 1730-36.

- NIKANDER, R., ET AL. “TARGETED EXERCISE AGAINST OSTEOPOROSIS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS FOR OPTIMISING BONE STRENGTH THROUGHOUT LIFE.” BMC MEDICINE, 8, NO.47 (JUL 2001). (EPUB). WWW.BIOMEDCENTRAL.COM/ARTICLES/10.11861/1741-7015-8-47 (ACCESSED MAY 13, 2016).

- MARTYN-ST JAMES, M. AND CARROLL, S. “A META-ANALYSIS OF IMPACT EXERCISE ON POSTMENOPAUSAL BONE LOSS: THE CASE FOR MIXED LOADING EXERCISE PROGRAMMES” [DATABASE OF ABSTRACTS OF REVIEWS OF EFFECTS (DARE): QUALITY ASSESSED REVIEWS]. BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, 43, NO. 12 (DEC 2009): 898-908. DOI: 10.1136/BJSM.2008.0527.

- NATIONAL OSTEOPOROSIS FOUNDATION. “CLINICIAN’S GUIDE TO PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF OSTEOPOROSIS.” WASHINGTON, DC: NATIONAL OSTEOPOROSIS FOUNDATION, 2010.

- SOUTH-PAUL, J.E. “OSTEOPOROSIS PART I: EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT.” AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN, 63, NO. 5 (MAR 2001): 897-905.

- IOM (INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE). DAILY REFERENCE INTAKES (DRIS): ESTIMATED AVERAGE REQUIREMENTS. IOM.NATIONALACADEMIES.ORG/ACTIVITIES/NUTRITION/SUMMARYDRIS/DRI-TABLES.ASPX (ACCESSED MAY 12, 2016).

- ZEHNACKER, C.H. AND BEMIS-DOUGHERTY, A. “EFFECT OF WEIGHTED EXERCISES ON BONE MINERAL DENSITY IN POST MENOPAUSAL WOMEN. A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW” [ABSTRACT]. JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PHYSICAL THERAPY, 30, NO. 2 (2007):

- 79-88.

- CHRISTO, K., ET AL. “BONE METABOLISM IN ADOLESCENT ATHLETES WITH AMENORRHEA, ATHLETES WITH EUMENORRHEA, AND CONTROL SUBJECTS.” PEDIATRICS, 121, NO. 6 (JUN 2008): 1127-36.

- NATTIV, A., ET AL. “AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SPORTS MEDICINE POSITION STAND. THE FEMALE ATHLETE TRIAD.” MEDICINE & SCIENCE IN SPORTS & EXERCISE, 39, NO. 10 (OCT 2007): 1867-82.

- KOHRT, W., ET AL. “AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SPORTS MEDICINE POSITION STAND: PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND BONE HEALTH.” MEDICINE & SCIENCE IN SPORTS & EXERCISE, 36, NO. 11 (NOV 2004): 1985-96.

- BORER, K.T. “PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN THE PREVENTION AND AMELIORATION OF OSTEOPOROSIS IN WOMEN: INTERACTION OF MECHANICAL, HORMONAL AND DIETARY FACTORS.” SPORTS MEDICINE, 35, NO. 9 (2005): 779-830.

- KEEN, R. “OSTEOPOROSIS: STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT. BEST PRACTICE & RESEARCH.” CLINICAL RHEUMATOLOGY, 21, NO. 1 (FEB 2007): 109-22.

- WITZKE, K.A. “OSTEOPOROSIS AND OSTEOPENIA.” IN ACE ADVANCED HEALTH & FITNESS SPECIALIST MANUAL (C.B. BRYANT & D.J. GREEN, EDS.). SAN DIEGO: AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EXERCISE, 2008.

- FUCHS, R.K. AND SNOW, C.M. “GAINS IN HIP BONE MASS FROM HIGH-IMPACT TRAINING ARE MAINTAINED: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.” JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS, 141, NO. 3 (SEP 2002): 357-62.

- FAIGENBAUM, A.D., ET AL. “YOUTH RESISTANCE TRAINING: UPDATED POSITION STATEMENT PAPER FROM THE NATIONAL STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING ASSOCIATION.” JOURNAL OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING RESEARCH, 23, NO. 5 (SUPPL) (AUG 2009): 60-79.

- DURSTINE, J.L., ET AL. (EDS.). ACSM’S EXERCISE MANAGEMENT FOR PERSONS WITH CHRONIC DISEASES AND DISABILITIES (3RD ED.). CHAMPAIGN: HUMAN KINETICS, 2009.