We all know the holidays are a time where we find it hard to resist the temptations of over-indulging, often leading to feelings of guilt, anger and disappointment if we lose the battle of the bulge. So what do many of us do?

We resolve to kick-start the New Year with a plan to trim that added holiday weight. Unfortunately, this act of conceding to the holiday festivities and waiting until the New Year (termed Waiting List Effect) is nothing short of an excuse to avoid some simple mindful efforts.

Efforts we could easily implement to help curb our excesses or weight gain. More importantly, by implementing some mindful strategies, especially this time of the year, we can avoid the discomfort associated with allowing ourselves to fall so far into despair where regaining our true form seems almost impossible, rather than possible or even probable.

Consider implementing some of these simple ideas that require only a modest amount of effort and notice the results for yourself!

**Just a reminder - you can check out some free nutrition courses from NASM. Follow the link to learn more.

Self-Awareness: Hunger versus Appetite

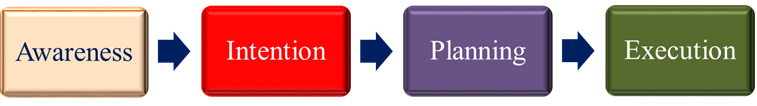

Increasing self-awareness of undesirable behaviors (i.e., making us more consciously aware of our actions) can help progress our well-meaning intentions into a formal plan. However, if there is not a means for execution, then any plan (no matter how well-intentioned) will most likely fail.

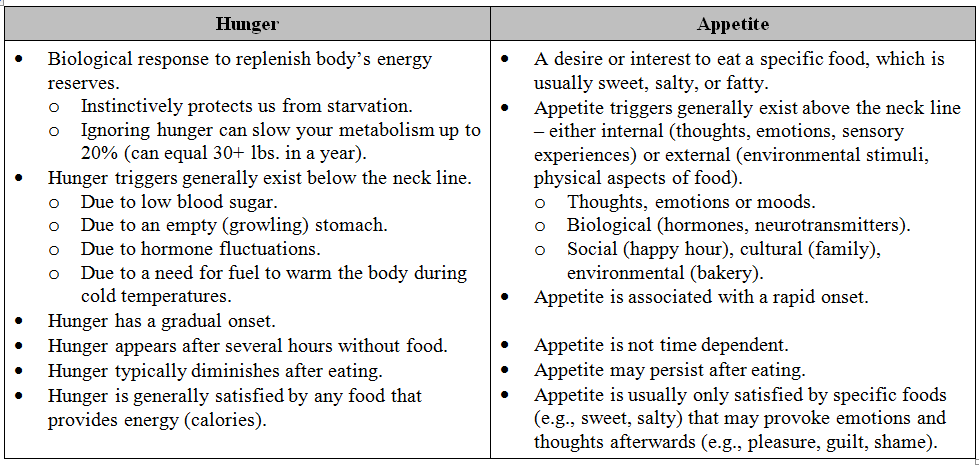

One effective strategy for improving self-awareness is to first differentiate hunger from appetite. Appetite appears to be the root of many cases of over-eating in America. While key differences are presented in the following table, hunger is essentially a biological response reminding us to replenish depleted energy reserves for physiological purposes, whereas appetite is a desire or interest to eat specific foods. Appetite can be triggered by various stimuli (i.e., smell of freshly baked bread, sight of a large desert buffet) in the absence of hunger that oftentimes results in impulsive consequences. In other words, you may eat due to your appetite even though you are not technically hungry.

One effective strategy for improving self-awareness is to first differentiate hunger from appetite. Appetite appears to be the root of many cases of over-eating in America. While key differences are presented in the following table, hunger is essentially a biological response reminding us to replenish depleted energy reserves for physiological purposes, whereas appetite is a desire or interest to eat specific foods. Appetite can be triggered by various stimuli (i.e., smell of freshly baked bread, sight of a large desert buffet) in the absence of hunger that oftentimes results in impulsive consequences. In other words, you may eat due to your appetite even though you are not technically hungry.

Although we have some conscious awareness to various eating triggers, most influence our sub-conscious mind, frequently driving us to eat mindlessly. Researchers demonstrated this when surveying individuals who believed they only made approximately 15-food related decisions on a daily basis. These researchers determined that we actually make approximately 200 food-related daily decisions, reinforcing the notion of a sub-conscious influence (1, 2).

Therefore, improving self-awareness to these stimuli offers a critical opportunity to exercise greater conscious control of eating. The fundamental idea for success is focused around awareness of the triggers in our own lives. Start with your dietary danger zones (e.g., times snacking at your desk, while driving, when bored, at social events or restaurants, etc.) and begin recording a log of any events, experiences or situations that act as a trigger (e.g., meeting with your boss, meeting your friends for happy hour). Over time, this aggregated information should reveal problematic areas that can then be addressed with a plan to control them.

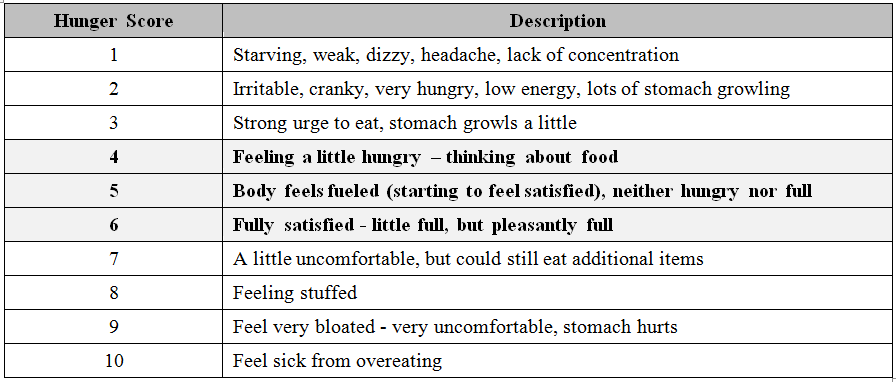

Another effective strategy is to learn to recognize and manage our own hunger levels, preventing unnecessary over-eating that can lead to increased body weight. Although hunger and appetite are quite different, they are often confused when trying to lose weight. Managing and not ignoring hunger is critical to weight loss. The practice of ignoring hunger should always be avoided because it significantly slows the body’s metabolic rate, which can impair any weight loss strategy.

Use the hunger scale presented below – aim to remain within the four-to-six score range as much as possible to avoid overeating and control unnecessary snacking (3). We have numerous biological responses that work to preserve energy reserves in the body and they push us to eat when those reserves become depleted (to some extent). Allowing your hunger scale to drop below a score of “4” will increase the tendency for binge eating as the body aggressively aims to restore energy reserves.

An interesting observation in the U.S. (where obesity is an issue), is that Americans tend to stop eating at a score of “7” whereas in leaner nations, individuals tend to stop eating at a score of “6”, eating less calories (1). Numerous reasons can be identified for this overeating that includes large portions sizes, our ‘clean the plate mentality’ and abundance (value) of available cheap food.

Portion Sizes

Success at changing our eating behaviors involves small initial victories that build our self-efficacy, which can in turn influence our attitudes and beliefs. Therefore, before telling clients what they should or should not eat, stop for a moment to explore whether you actually understand why certain choices are made (i.e., seek to understand before being understood).

Why would you ever tell someone to eliminate a food that may be connected to some deeply rooted emotion or experience? Remember, eating is a social and experiential behavior that needs to be fully understood before making any change. Given this logistical challenge, perhaps we should consider tackling existing eating behaviors in a simpler way; by reducing portion sizes.

Portion sizes they have steadily increased by 15 – 70% over the past 40 years due to various economic, social, technological and other reasons. As portion sizes have slowly increased during this time, we have sub-consciously lost track of a standard serving size, and now consume more calories than ever before (4). Coincidently plates and cups have also become larger to accommodate bigger servings, so mini-size your plates and glasses (e.g., use side plates). R

esearchers using Chex Mix® served in various sized bowls found that individuals consumed 59% more calories when eating out of the larger bowls (5). Another study using 5-day old popcorn (described as tasting like Styrofoam®) also found that even with horrible-tasting food, people eating out of the larger containers consumed 53% more food (6).

By strategically mini-sizing eating utensils (using smaller plates and glasses), the perception of food eaten can be positively influenced as illustrated below. This can reduce total caloric intake. Researchers have also determined that reducing portion sizes up to 20% usually go unnoticed, whereas reducing portions sizes by up to 30% or more creates more conscious awareness to the reductions and increased perceptions of being deprived of food and choices, which can lead to threats to change (1).

Read also: Nutrition and Behavior Change.

For a deeper dive into portion sizes, try out course on the subject today! The course is a part of our flagship nutrition certification program.

References:

- Wansink, B. (2006). Mindless Eating – Why we eat more than we think. New York, NY: Bantam-Dell Books.

- Wansink, B., & Sobel, J. (2007). Hidden persuaders and 200 daily decisions. Environment and Behavior, (39(1): 106-123.

- Ominchanski, L. (1992), You count, calories don’t. Center for Health Promotion and Wellness, MIT Medical.

- NHANES, 2008. Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients in Adults from 1999-2000 through 2007-2008. NCHS Data Brief. Number 49, November 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db49.htm; retrieved 09/01/12.

- Wansink, B. & Park, S. (2001). At the movies: How external cues and perceived taste impact consumption volume. Food Quality and Preference, 12(1): 69-74.

- Wansink, B. & Cheney. M.M. (2005). Super Bowls: Serving bowl size and food consumption. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(14): 1727-1728.