Are you feeling sluggish? Are you having difficulty losing weight? Maybe you should SPEED your metabolism.

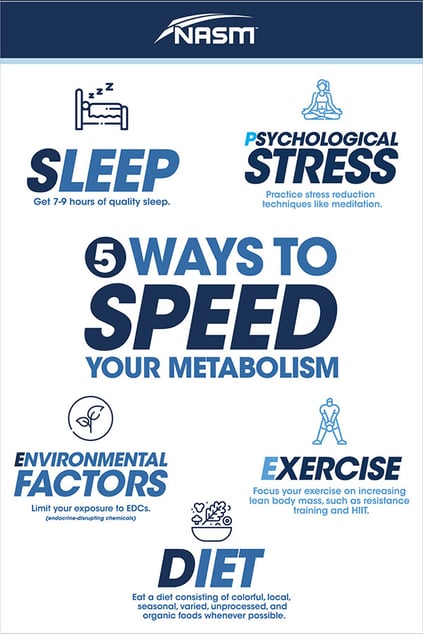

This blog post will show you 5 ways to do exactly that with the acronym SPEED, which stands for Sleep, Psychological Stress, Environment, Exercise, and Diet

Be sure to check out the NASM course on metabolism while you're at it!

5 Ways to Speed up Your Metabolism

These 5 ways to speed up metabolism are best understood with the acronym SPEED:

S- Get 7-9 hours of quality sleep.

P- Practice stress reduction techniques like meditation.

E- Limit your exposure to EDCs.

E- Focus your exercise on increasing lean body mass, such as resistance training and HIIT.

D- Eat a diet consisting of colorful, local, seasonal, varied, unprocessed, and organic foods whenever possible.

Let's jump into the science behind SPEEDing up your metabolism!

This information goes hand-in-hand with the NASM Weight Loss Coach Course Bundle. If you want a free teaser of the topics discussed within the WLS curriculum, check out our mini course on The Science Behind Effective Weight Loss.

#1 Sleep

We are a sleep-deprived society with evidence showing that we sleep an average of 6.8 hours per night instead of the recommended 7-9 hours recommended for adults by the National Sleep Foundation.

Sleep is intricately connected to numerous hormonal and metabolic processes and is a key to maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Poor sleep hygiene has profound metabolic and cardiovascular implications and is believed to cause metabolic dysregulation through sympathetic overstimulation, hormonal imbalance, and low-grade inflammation.

Sleep deprivation can alter the glucose metabolism and hormones involved in regulating metabolism, such as decreased leptin levels and increased ghrelin levels. Chronic sleep deprivation is also associated with an increased risk of obesity and diabetes.

(Sharma, S., & Kavuru, M., 2010)

Sleep hygiene tips:

1. Start a bedtime routine.

2. Have a wind-down period and regular bedtime.

3. Turn off your electronics and keep them away from where you sleep.

4. Maintain a cool, dark, and quiet sleep environment.

5. Avoid caffeine late in the day and alcohol in the evening.

6. Avoid processed foods and sugar.

7. Get some outside time during the day.

8. Consider a sleep study to evaluate for apnea if you have chronic insomnia.

9. Consult your healthcare provider regarding using supplements (e.g., melatonin, valerian root, lemon balm, and CBD).

(Bubbs, M., 2019)

#2 Psychological Stress

The body reacts to acute stress via a "fight or flight" response, which activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to release the corticotropin-releasing hormone. This, in turn, stimulates the sympathetic nervous system.

Acute stress is commonly associated with a reduction in appetite and reduced body weight. However, chronic stress can lead to overconsumption of hyper-palatable foods, resulting in increased visceral adiposity and weight gain.

The obesogenic effects of chronic stress are mediated through the release of glucocorticoids and neuropeptide Y, which can adversely affect metabolism.

(Rabasa, C., & Dickson, S. L., 2016)

See also this NASM blog about stress and its health effects.

Stress management tips:

1. Meditation can lower cortisol levels in the blood and the subsequent adverse physiological effects of stress. Start with fifteen minutes daily.

2. Exercise affects neurotransmitters in the brain, such as dopamine and serotonin, which affect mood and behavior and improve the way the body handles stress. Aim for some form of exercise daily.

3. Adaptogenic herbs such as ashwagandha can help modify the stress response. Consult your healthcare provider.

(Chandrasekhar, K., Kapoor, J., & Anishetty, S., 2012) (Jackson, Erica M., 2013) (Turakitwanakan W, Mekseepralard C, Busarakumtragul P., 2013)

#3 Environmental Factors

Synthetic chemicals ubiquitous in our society are leading to widespread contamination of the environment. These include (but are not limited to) pesticides, plasticizers, parabens, VOCs, antimicrobials, and flame retardants. These endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can disrupt hormonal balance and result in developmental and reproductive abnormalities, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

Limiting exposure to EDCs by opting for organic foods and chemical-free, self-care products, cosmetics, cookware, cleaning products, furniture, etc., can lessen the load on one’s endocrine system, lower the risk for obesity and have a more favorable effect on metabolism.

(Casals-Casas C, Desvergne B., 2011)

The Environmental Working Group is a useful resource for limiting your environmental chemical load.

#4 Exercise

Resistance training has the potential to increase metabolic rate and daily energy expenditure. The principal mechanism is by augmenting fat-free mass (FFM). Increasing protein intake during a resistance training program produces additional increases in FFM. Increasing lean body mass can also improve insulin sensitivity and lower the risk for diabetes

(Aristizabal, J. et al, 2015).

High-Intensity Interval Training and the concomitant Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption (EPOC) can also boost your metabolic rate. EPOC is the amount of oxygen required to restore your body to homeostasis.

See this blog post on EPOC to learn more!

The Role of Oxygen During the the post-exercise recovery period

1. The production of ATP to replace the ATP used during the workout.

2. Resynthesis of muscle glycogen from lactate.

3. Restoration of oxygen levels in venous blood, skeletal muscle blood, and myoglobulin.

4. Repair of muscle tissue damaged during the workout.

5. Restoration of body temperature to resting levels.

(Foureaux, G., Pinto, K. M. D. C., & Dâmaso, A., 2006)

Exercise programming to increase metabolism:

1. Resistance training.

● 3–6 times per week, with 2–4 strength exercises per body part

● 3–5 sets

● 6–12 reps

● 2/0/2 tempo

● 75%–85% intensity

● 0- to 60-second rest interval

2. HIIT 2x/week. Example: stationary bike. Pedal as hard and fast as possible for 30 seconds, then pedal at a slow, easy pace for one to two minutes. Repeat for 15 to 30 minutes.

See this blog on HIIT Workouts for great ideas!

(Clark, M. A., Lucett, S., & Corn, R. J., 2008)

#5 Diet

Protein-rich foods, such as meat, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, nuts, and seeds, could help increase your metabolism for a few hours after a meal as your body uses more energy to digest them.

Due to TEF, the energy needed by your body to digest, absorb and process nutrients. TEF from protein can increase your metabolic rate by 15–30%, compared to 5–10% for carbs and 0–3% for fats.

Because protein-rich diets support lean body mass, they can also reduce the drop in metabolism often seen during weight loss. Protein may also help keep you fuller for longer, which can prevent overeating.

Check out - How Much Protein for Weight Loss - for more great information on the subject. And check out our weight loss calculator app to keep your diet on track!

(Dougkas A, Östman E., 2016) (Mettler S, Mitchell N, Tipton KD., 2010) (Pesta, D. H., & Samuel, V. T.,2014)

The microbiome

The gut contains more than 100 trillion microorganisms, collectively called the microbiota. The microbiota performs several functions in the body, including setting our metabolism, breaking down and assimilating food, neutralizing drugs and carcinogens, and synthesizing vitamins, short-chain fatty acids, and secondary bile acids.

Several factors can adversely affect the diversity and health of the microbiome. These include a diet high in refined carbohydrates and omega-6 vegetable oils, a long-term ketogenic diet, overtraining, stress, travel, and drugs such as antibiotics, NSAIDs, and Proton Pump Inhibitors.

(Bubbs, M., 2019)

See also - A Gut Check on Health - for more information on the microbiome.

Nutrition tips to optimize metabolism:

● Eat a varied diet focusing on colorful vegetables and fruits along with legumes and beans.

● Include fermented foods such as kimchi, sauerkraut, pickles, tempeh, yogurt and kombucha.

● Consider taking a probiotic.

Metabolism 101 (Total Daily Energy Expenditure - TDEE)

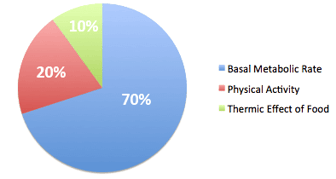

There are three primary components to your body’s TDEE:

1. Metabolic Rate (BMR)

2. Activity Energy Expenditure (AEE)

3. Thermic Effect of Food (TEF)

Metabolic Rate

Metabolic rate is the measurement of the number of calories needed to perform your body's most basic functions, like breathing, circulation, and cell production. It is influenced by age, gender, height, weight, body composition, hormones, stress, sleep, the environment, genetics, and health.

You can measure metabolic rate by determining how much oxygen your body consumes over a specific amount of time. Indirect calorimetry measures O2 consumption and CO2 production using a metabolic cart. Direct calorimetry measures an individual's heat production, in calories, when placed in an insulated chamber where the heat is transferred to the surrounding water.

Fortunately, since most of us don’t have access to direct and indirect calorimetry, there are formulas that can be used to measure metabolism, such as Cunningham and Harris-Benedict.

Learn how to calculate your resting metabolic rate by following the link

Physical Activity (Activity Energy Expenditure - AEE)

AEE encompasses formal exercise, such as resistance training, aerobic activity, sports, recreational activities, and Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT).

The amount of energy expended through exercise is commonly calculated using metabolic equivalents (METS). A MET is a ratio of your working metabolic rate relative to your resting metabolic rate. It is a reflection of the intensity of an exercise or activity. One MET is defined as the energy you use when you’re resting or sitting still (1 MET= 3.5 milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram of body weight per minute).

Thermic Effect of Food (TEF)

TEF is the energy required for digestion, absorption, and disposal of ingested nutrients. Its magnitude depends on the composition of the food consumed, with protein having the most significant effect.

References

Aristizabal, J., Freidenreich, D., Volk, B. et al. Effect of resistance training on resting metabolic rate and its estimation by a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry metabolic map. Eur J Clin Nutr 69, 831–836 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.216.

Bubbs, M. (2019). PEAK: The new science of athletic performance that is revolutionizing sports. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Casals-Casas C, Desvergne B. Endocrine disruptors: from endocrine to metabolic disruption. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:135-62. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-Physiol-012110-142200. PMID: 21054169.

Chandrasekhar, K., Kapoor, J., & Anishetty, S. (2012). A prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of a high-concentration full-spectrum extract of ashwagandha root in reducing stress and anxiety in adults. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 34(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.106022.

Clark, M. A., Lucett, S., & Corn, R. J. (2008). NASM essentials of personal fitness training. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Douglas A, Östman E. Protein-Enriched Liquid Preloads Varying in Macronutrient Content Modulate Appetite and Appetite-Regulating Hormones in Healthy Adults. J Nutr. 2016 Mar;146(3):637-45. DOI: 10.3945/Jn.115.217224. Epub 2016 Jan 20. PMID: 26791555.

Foureaux, G., Pinto, K. M. D. C., & Dâmaso, A. (2006). Effects of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and resting metabolic rate in energetic cost. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 12(6), 393-8.

Jackson, Erica M. Ph.D., FACSM STRESS RELIEF: The Role of Exercise in Stress Management, ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal: May/June 2013 - Volume 17 - Issue 3 - p 14-19 DOI: 10.1249/FIT.0b013e31828cb1c9.

Mettler S, Mitchell N, Tipton KD. Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Feb;42(2):326-37. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b2ef8e. PMID: 19927027.

Pesta, D. H., & Samuel, V. T. (2014). A high-protein diet for reducing body fat: mechanisms and possible caveats. Nutrition & metabolism, 11(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-11-53.

Rabasa, C., & Dickson, S. L. (2016). Impact of stress on metabolism and energy balance. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 9, 71-77.

Sharma, S., & Kavuru, M. (2010). Sleep and metabolism: an overview. International journal of endocrinology, 2010, 270832. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/270832.

Turakitwanakan W, Mekseepralard C, Busarakumtragul P. Effects of mindfulness meditation on serum cortisol of medical students. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013 Jan;96 Suppl 1:S90-5. PMID: 23724462.