Health and fitness assessments have become increasingly more detailed over the years.

These assessments assist fitness professionals (like corrective exercise professionals) in gathering as much valuable subjective (e.g., PAR-Q+ and Lifestyle and Health History Questionnaire) and objective (e.g., anthropometric data, body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, etc.) information as possible to design the most individualized and effective exercise program for clients.

Over the last decade or so, more and more fitness professionals have begun to include both a static postural assessment and a dynamic postural assessment (i.e., overhead squat assessment, single-leg squat assessment, and pushing/pulling assessments) into their clients’ health and fitness assessment.

These assessments provide invaluable information on possible muscular imbalances (i.e., overactive/shortened or underactive/lengthened muscles) that may lead to static postural deviations (e.g., pes planus syndrome, lower-crossed syndrome, and upper-crossed syndrome) and dynamic movement impairments (e.g., feet turning out, knees moving in, excessive forward lean, low back arches, arms fall forward, etc.) that may ultimately lead to acute or chronic injury and pain via the cumulative injury cycle (National Academy of Sports Medicine, 2022).

STATIC AND DYNAMIC POSTURAL ASSESSMENTS VS. JOINT RANGE OF MOTION TESTING

Although both a static and dynamic postural assessment may assist in detecting possible muscular imbalances, unfortunately, these assessments cannot definitively confirm specific muscles to be overactive/shortened, or underactive/lengthened. Therefore, the ability of the fitness professional to measure joint range of motion (ROM) can be a valuable tool in confirming the assumptions of probable overactive/shortened muscles.

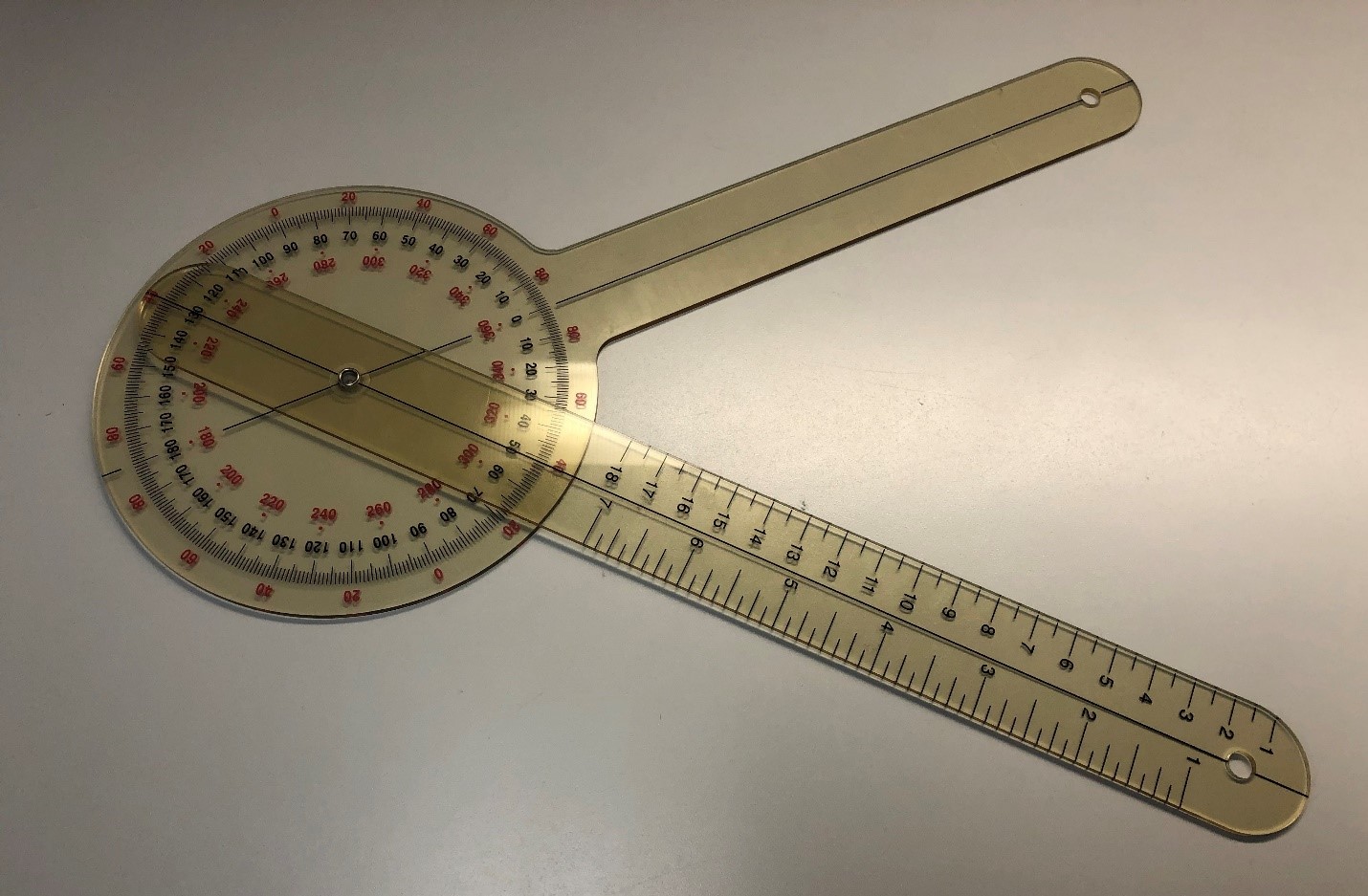

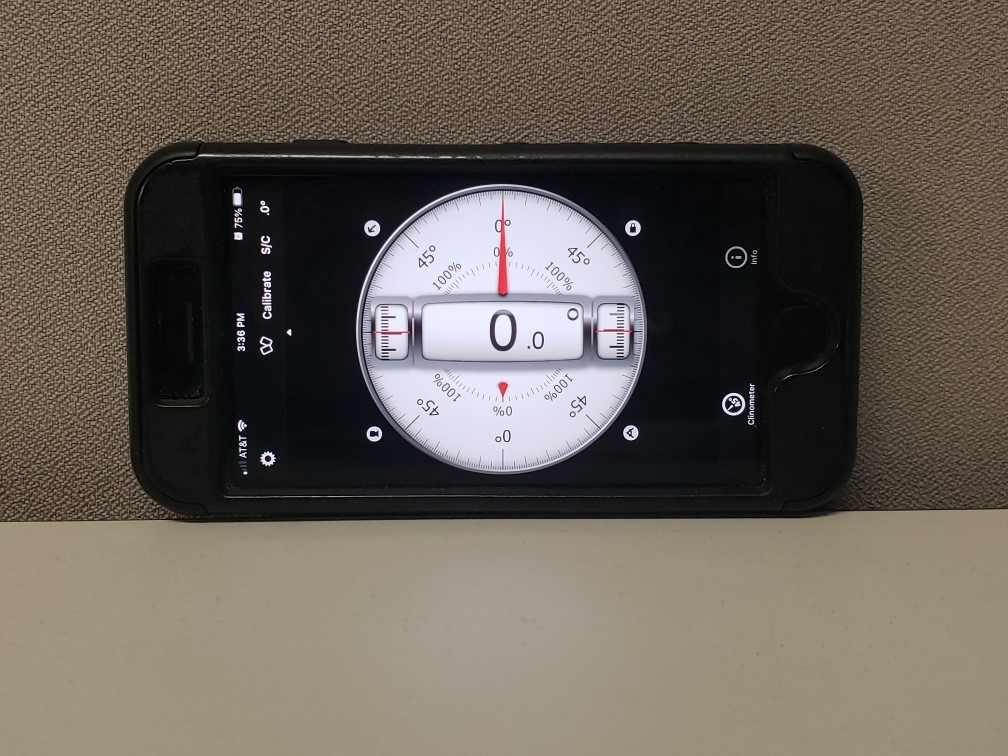

However, many fitness professionals may not have the formal education and experience in measuring ROM through the use of a goniometer (Figure 1) and/or inclinometer (Figure 2) that is commonly part of the course curriculum in college degree programs such as kinesiology, exercise science, athletic training, and physical therapy. In addition, the skill of assessing ROM through goniometry and inclinometer takes many hours of practical experience under formal instruction to master and be considered valid and reliable.

Figure 1. Goniometer

Figure 2. Baseline® digital inclinometer

Therefore, the purpose of this three-part series is to assist fitness professionals in learning to measure ROM utilizing an application on their smartphone (Figure 3), which is both valid and reliable when compared to other forms of measurement, such as goniometry and inclinometer (Wellmon, Gulick, Paterson, & Gulick, 2016) at multiple significant joints throughout the body, such as the ankle, knee, hip, shoulder, elbow, wrist, and spine (Keogh, Cox, Anderson, Liew, Olsen, Schram, & Furness, 2019).

Figure 3. Smartphone inclinometer application (Clinometer + Bubble Level application by Peter Breitling, available on IOS and Android)

MOBILITY ASSESSMENTS, JOINT RANGE OF MOTION, AND THE FITNESS PROFESSIONAL

In 2020, the National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM) released their much-anticipated updated Corrective Exercise Specialization (CES) certification course, as well as the certification textbook resource Essentials of Corrective Exercise Training (2nd ed.). Within the CES course and textbook, Chapter 10, "Mobility Assessments," includes multiple mobility assessments for the lower extremities (i.e., the foot and ankle, and knee), lumbopelvic hip complex or LPHC, shoulders and thoracic spine, elbow and wrist, and head and cervical spine (National Academy of Sports Medicine, 2022).

The inclusion of specific mobility assessments into a client's health and fitness assessment assists in measuring soft tissue extensibility and confirms overactive/shortened muscles based on the fitness professional's previous observations during the static and dynamic postural assessments. However, the mobility assessments within the CES course and textbook only provide instruction for assessing mobility through visual observational measurements and benchmarks.

For example, "normal mobility" during the active knee flexion assessment is represented by the ability of the client to bring the foot close to or touching their buttocks without compensation (Figure 4) (National Academy of Sports Medicine, 2022).

Figure 4. Active knee flexion mobility assessment

Although this method of assessment assists the fitness professional in determining the extensibility of the quadriceps complex, it does not provide the fitness professional with an objective measurement of active knee flexion ROM (e.g., 120 degrees) that the use of a smartphone application would provide if the client demonstrated limited knee flexion mobility (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Measuring active knee flexion with a smartphone inclinometer application

By simply using visual observational measurements to determine a client's mobility, the fitness professional will not be able to monitor objective improvements in mobility (i.e., increases in ROM measured in degrees) when reassessing clients throughout their fitness program.

This three-part series will, in turn, instruct the fitness professional how to objectively measure ROM through the use of a smartphone application to show progressive improvements in ROM within joints that may demonstrate limited mobility.

Please note, measuring a client's active ROM is within the fitness professional's scope of practice. However, if the client expresses pain during any mobility assessment, the fitness professional is required to refer the client to a qualified healthcare professional for further evaluation.

WHAT TO EXPECT FROM THIS THREE-PART SERIES

This piece is the first of a three-part series that will assist the fitness professional in learning to objectively measure ROM utilizing a smartphone application while performing the mobility assessments used by NASM through their CES course and textbook. Part II of this series will focus on measuring ROM while performing mobility assessments of the lower extremities (i.e., weight-bearing lunge, knee flexion, and knee extension) and LPHC (i.e., modified Thomas test, hip internal rotation, and external hip rotation).

At the same time, Part III will instruct the fitness professional on how to measure ROM at the shoulder (i.e., flexion, extension, internal rotation, and external rotation), elbow (i.e., elbow flexion), and wrist (i.e., flexion and extension) joints.

References:

- Keogh, J. W. L., Cox, A., Anderson, S., Liew, B., Olsen, A., Schram, B., & Furness, J. (2019). Reliability and validity of clinically accessible smartphone applications to measure joint range of motion: A systematic review. PloS One, 14(5), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215806

- National Academy of Sports Medicine (2022). Essentials of corrective exercise training (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Wellmon, R. H., Gulick, D. T., Paterson, M. L., & Gulick, C. N. (2016). Validity and Reliability of 2 Goniometric Mobile Apps: Device, Application, and Examiner Factors. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 25(4), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2015-0041

Student in Figures: Darcel Tinner (Health & Human Performance major)

Student Photographer: Dana Timpson (Exercise Science major)

ROM Tester in Figures: Dr. Ryan R. Fairall