Your client has just recovered from COVID-19 and is cleared by the medical professional to return to exercise. The client contacts you to schedule a training session.

After scheduling the client, you begin to think of the comprehensive nature of COVID-19 and develop several questions such as but not limited to: what are the long-term effects of COVID-19 that can affect a client’s workout? Are there any guidelines for training the post-COVID-19 client?

Can the post-COVID-19 client be overtrained? What are the long-term effects of regular exercise, good diet, and wellness for these clients? Since the onset of the COVID-19, a large body of research has addressed such questions.

This discussion will cover the latest evidence on fitness training for the post-COVID-19 client. You can explore this subject further by signing up for our course on COVID Management or by checking out our fitness resource page on COVID.

What is COVID-19?

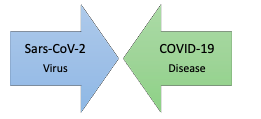

The coronavirus is a large family of viruses in which seven variants cause disease in humans. The most notable coronaviruses are severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) found in 2002 in China. In 2019, a new coronavirus variant emerged named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

The new virus created similar signs and symptoms as SARS which prompted the initial creation of the name SARS-CoV-2 (CDC, 2021). In early 2020, the name changed to COVID-19, which is the most used to date. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 is the virus, and COVID-19 is the disease that causes the signs and symptoms that people experience (e.g., respiratory issues) when they have the illness.

What are the long-term effects of COVID-19?

Most Individuals who contract COVID-19 recover within two weeks with little or no symptoms (CDC, 2021). However, a subset of individuals with co-morbid conditions are at high risk for severe COVID-19 illness.

The co-morbid conditions include but are not limited to diabetes, obesity, heart disease and stroke, pulmonary disease, severe hypertension, chronic kidney and gastrointestinal disease, and sickle cell disease. Smoking and pregnancy are also reported risk factors (Ejaz et al., 2020).

Researchers have found that 80% of individuals hospitalized with COVID-19 experienced at least one lingering symptom six months after recovering (Lopez-Leon et al., 2021). The five most common long-term complications include fatigue (58%), headache (44%), attention disorder (e.g., COVID-19 fog) (27%), hair loss (25%), and shortness of breath (24%) (Lopez-Leon et al., 2021).

Other common long-term complications may include but are not limited to cough, chest pain, intermittent fever, musculoskeletal pain, and heart palpitations (CDC, 2021). Individuals with long-term complications are often classified as "long haulers" due to lingering issues (Marshall, 2020).

The fitness professional needs to understand common long-term complications since they may influence the client's ability to participate in the exercise. NASM recommends that fitness professionals work closely with the client's medical provider to understand which long-term complications are present and how safely train them.

What are exercise guidelines for Post-COVID-19 clients?

Researchers have documented exercise recommendations for post-COVID-19 clients. A recommended programming strategy for fitness professionals is to use the FITTE principle (frequency, intensity, time, type, enjoyment) (Burnet et al., 2019). Integrating the FITTE principle into NASM's Optimum Performance Training (OPT) model is easy given the model's adaptability.

For clients with a low to moderate exercise capacity, the FITTE principle for aerobic exercise, resistance training, and flexibility may be ideal (Sheehy, 2020). These clients may have a limited exercise capacity due to their current health status. For clients with a moderate exercise capacity or higher, the NASM-OPT model may be ideal since these clients can participate in a more comprehensive program. These integrated recommendations are discussed below (Sheehy, 2020).

FITTE Recommendations: Low to moderate level activity

Aerobic Exercise

• Frequency: A goal of 3 to 5 training days per week is optimal to begin. Clients can be progressed, as tolerated.

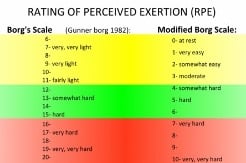

• Intensity: Light to moderate-intensity exercise (40-60% of peak work capacity, RPE 3-4/1-10 scale, RPE 12-13/ 6-20 scale) with further monitoring and evaluation.

• Time: Clients can accumulate up to 30-60 minutes of aerobic exercise each training day. Progression can occur at a steady pace.

• Type: Clients should participate in standard modes of aerobic exercise, including walking, biking, and cardiovascular equipment (e.g., elliptical, treadmill, stationary bike) as tolerated.

• Enjoyment: Clients may be more willing to exercise when doing aerobic activities they enjoy in the optimal environment.

*RPE= rate of perceived exertion

Resistance Exercise

• Frequency: Based upon client tolerance. A goal of 2 to 3 training days per week is optimal, if safe for the client.

• Intensity: Low‐medium intensity clients: 30% to 40% of 1 RM; A repetition continuum can also be used beginning with 1 set of 12-20 reps with progression as tolerated.

• Time: Determined by client's ability to complete their resistance training program.

• Type: Clients should use standard modes of training such as body weight, resistance bands, free weights, machines, and other objects (e.g., medicine ball) as tolerated.

• Enjoyment: Clients may be more willing to exercise when they do resistance exercise; they enjoy the optimal environment.

*RM= repetition maximum

Flexibility Exercise

• Frequency: Based upon client tolerance. A goal of 2 to 3 training days per week is optimal, if safe for the client.

• Intensity: As tolerated by the client. Stretching and rolling should not be painful.

• Time:

• Self-myofascial rolling: Hold tender area 30 seconds for 1 to 3 sets.

• Static stretching: 10 to 30 seconds for 1 to 3 sets.

• Active stretching: Hold each stretch for 1 to 2 seconds for 5 to 10 repetitions.

• Type: Clients should use common modes of flexibility include self-myofascial rolling, static stretching, and active stretching. The client should avoid discomfort with any of these techniques.

• Enjoyment: Clients may be more willing to stretch when they are doing stretches they enjoy the optimal environment.

|

Important It is recommended for fitness professionals to take the client blood pressure prior to training and obtain their subjective RPE throughout their exercise program. The fitness professional can also use a pulse oximeter to monitor their clients heart rate and blood oxygen saturation (normal 95-100%) (CDC, 2021).

|

NASM OPT Model: Moderate level activity or higher

Some clients may have recovered from COVID-19 with minimal to no lingering complications, or some clients who began at a lower exercise capacity may have improved. In either case, these clients may be ready for a more comprehensive exercise program. It is recommended to begin all clients in the NASM-OPT Phase I: Stabilization Endurance Training.

The focus of the lower-intensity resistance training used in Phase I may help address many of the potential health issues that can occur to post-COVID-19 clients (Zeng et al., 2020). This program is much more comprehensive than the FITTE recommendations due to the many types of exercises integrated into a session. A recommended goal is for clients to complete all desired activities in Phase I before moving on to Phase II. This may help them safely adapt to the different exercises and prepare their body for high-level training.

Can the post-COVID-19 client be overtrained?

Post-COVID-19 clients might be deconditioned due to lack of physical activity, putting them at risk for overtraining syndrome if they progressed too quickly (Caterisano et al., 2019).

Overtraining syndrome is when the training has gone too far. The client begins to experience systemic inflammation and adverse neurophysiological effects that decrease performance during physical activity. Overtraining syndrome often includes a cluster of symptoms (Table 1) (Kreher & Schwartz, 2012). The fitness professional should understand the signs and symptoms of overtraining syndrome to train the post-COVID-19 client safely.

NASM recommends using the FITTE recommendations or NASM OPT-Level 1 as a starting point for these clients. They may need some time to adapt to their program and deal with any lingering complications. This requires a safe and systematic return to physical activity.

|

Table 1: Symptom Associated with Overtraining Syndrome |

||

|

Parasympathetic Alterations |

Sympathetic Alterations |

Other |

|

Fatigue |

Insomnia |

Anorexia |

|

Depression |

Irritability |

Weight loss |

|

Slow pulse rate (Bradycardia) |

Agitation |

Lack of mental concentration |

|

Loss of motivation |

Fast pulse rate (Tachycardia) |

Anxiety |

|

|

Hypertension |

Awakening unrefreshed |

|

|

Restlessness |

|

What are the benefits of regular exercise, good diet, and wellness for Post-COVID-19 clients?

Researchers have documented the importance of regular exercise, good dietary habits, and wellness practices to improve overall health (mental and physical) and immune function (Butler & Barrientos, 2020). Table 2 outlines the potential benefits of regular exercise, good dietary choices, and wellness practices during this time (De Sousa et al., 2021).

Researchers recently published a large-scale study of 48,400 adults with COVID-19. The researchers found that inactive individuals (less than 10 min per week of exercise) had a greater risk of hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, and death due to COVID-19. More active individuals (Up to 150+ minutes of exercise per week) had more minor risk factors (Sallis et al., 2021). This emerging evidence supports the idea that physical activity is essential to a client’s health and wellness.

|

Table 2: Potential benefits of regular exercise, good dietary habits, and wellness practices |

|

|

Improve immune system function |

Reduced risk for chronic conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease) |

|

Improve mental health |

Reduced risk for metabolic conditions (e.g., diabetes) |

|

Improved cardiovascular function |

Maintenance of musculoskeletal strength |

|

Prevention of excessive weight gain |

Maintenance of joint mobility and soft-tissue flexibility |

Conclusion

NASM recommends a systematic programming strategy for the post-COVID-19 client. Good communication with the client’s medical provider is recommended.

The information provided in this discussion represents the most current evidence on COVID-19 as it relates to fitness. Please see the new NAME [NASM COVID-19 Course] that provides more comprehensive coverage of this topic.

References

Burnet, K., Kelsch, E., Zieff, G., Moore, J. B., & Stoner, L. (2019, Feb 1). How fitting is F.I.T.T.?: A perspective on a transition from the sole use of frequency, intensity, time, and type in exercise prescription. Physiol Behav, 199, 33-34.

Butler, M. J., & Barrientos, R. M. (2020, Jul). The impact of nutrition on COVID-19 susceptibility and long-term consequences. Brain Behav Immun, 87, 53-54.

Caterisano, A., Decker, D., Snyder, B., Feigenbaum, M., Glass, R., House, P., Sharp, C., Waller, M., & Witherspoon, Z. (2019). CSCCa and NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods: Safe Return to Training Following Inactivity. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 41(3), 1-23.

CDC. (2021). COVID-19 Page. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html

De Sousa, R. A. L., Improta-Caria, A. C., Aras-Júnior, R., de Oliveira, E. M., Soci Ú, P. R., & Cassilhas, R. C. (2021, Jan 25). Physical exercise effects on the brain during COVID-19 pandemic: links between mental and cardiovascular health. Neurol Sci, 1-10.

Ejaz, H., Alsrhani, A., Zafar, A., Javed, H., Junaid, K., Abdalla, A. E., Abosalif, K. O. A., Ahmed, Z., & Younas, S. (2020). COVID-19 and comorbidities: Deleterious impact on infected patients. Journal of infection and public health, 13(12), 1833-1839.

Kreher, J. B., & Schwartz, J. B. (2012). Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports health, 4(2), 128-138.

Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Perelman, C., Sepulveda, R., Rebolledo, P. A., Cuapio, A., & Villapol, S. (2021, Jan 30). More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv.

Marshall, M. (2020, Sep). The lasting misery of coronavirus long-haulers. Nature, 585(7825), 339-341.

Sallis, R., Young, D. R., Tartof, S. Y., Sallis, J. F., Sall, J., Li, Q., Smith, G. N., & Cohen, D. A. (2021). Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports-2021-104080.

Sheehy, L. M. (2020). Considerations for Postacute Rehabilitation for Survivors of COVID-19. JMIR public health and surveillance, 6(2), e19462-e19462.

Zeng, B., Chen, D., Qiu, Z., Zhang, M., Wang, G., Rehabilitation Group of Geriatric Medicine branch of Chinese Medical Association, d. o. M. o. M. R. I. o. C. H. A. R. I. M. d. o. C. R. M. A. d., Wang, J., Yu, P., Wu, X., An, B., Bai, D., Chen, Z., Deng, J., Guo, Q., He, C., Hu, X., Huang, C., Huang, Q., Huang, X., Huang, Z., Li, X., Liang, Z., Liu, G., Liu, P., Ma, C., Ma, H., Mi, Z., Pan, C., Shi, X., Sun, H., Xi, J., Xiao, X., Xu, T., Xu, W., Yang, J., Yang, S., Yang, W., Ye, X., Yun, X., Zhang, A., Zhang, C., Zhang, P., Zhang, Q., Zhao, M., & Zhao, J. (2020). Expert consensus on protocol of rehabilitation for COVID-19 patients using framework and approaches of WHO International Family Classifications. Aging medicine (Milton (N.S.W)), 3(2), 82-94.