Originally published in the Summer 2019 issue of American Fitness Magazine.

Cancer is serious

business. It is second only to heart disease as Americans’ leading

cause of death, and more than 1.7 million new cases of cancer are expected to

be diagnosed this year. Of those new cases, many will be invasive breast cancer

(an estimated 268,600 in women and 2,670 in men), with nearly another 63,000

“in situ” (early stage) breast cancers in women (ACS 2019). As we near the year

2030, when all of the baby boomers will be 65 or older, the number of people

facing cancer is likely to increase, too, since both chronological age and

biological age are strong predictors of this disease (USCB 2018; Kresovich et

al. 2019).

While

these statistics are sobering, there are more-encouraging numbers, too: Nearly

half of these new cancers (about 42%) can be prevented through healthy

lifestyle changes. In fact, about 18% of them are caused by a combination of

excess body weight, physical inactivity, poor nutrition and excess intake of

alcohol (ACS 2019). So, the work that fitness professionals are doing today may

be helping to prevent clients from developing cancer in the first place.

For

those who do receive a cancer diagnosis, exercise trainers and instructors can

also make a difference—by encouraging them to engage in regular exercise and

healthier eating before, during and after treatment. These healthy habits have

been proven to minimize the debilitating side effects—acute and chronic—of the

condition itself, as well as those caused by medications, treatment and

surgeries.

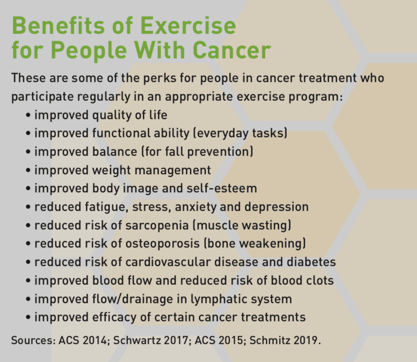

In addition, regular exercise can improve the efficacy of cancer treatments and, with proper programming and progression, can result in clients/patients becoming stronger than they were prior to their diagnosis. Exercise has even been found to reduce the likelihood of recurrence (ACS 2015; Ashcraft et al. 2019). (See “Benefits of Exercise for People With Cancer” for more.)

Should Cancer Be Part of Your Business?

With about 15.5 million Americans—about 5% of today’s population—living with cancer, it is likely that most fitness professionals will encounter clients whose abilities, goals and fitness programming will be affected by this disease (ACS 2019; ACS 2014; USCB 2019). For trainers who would like to work with such clients, it is vital to understand the unique concerns of this population, says Andrea Leonard, whose diagnosis of thyroid cancer at the age of 18 inspired her to become an NASM-CPT, CES, PES. Since then, she has earned worldwide recognition for her expertise on cancer and exercise; co-written one of the first books on this topic, Essential Exercises for Breast Cancer Survivors: How to Live Stronger and Feel Better (The Harvard Common Press 2000); founded The Cancer Exercise Training Institute (CETI); and developed the Cancer Exercise Specialist® Advanced Qualification and other courses for fit pros.

“This

is a much higher-risk group than the average person,” says Leonard. “You need

to have a complete understanding of all acute and chronic side

effects—including those related to any kind of surgery/treatment clients have

had (or are currently undergoing)—and [you must know] how to create a program

that will prevent, minimize and correct any of those elements.”

Anna

Schwartz, PhD, FNP, FAAN, agrees. This world-renowned researcher and author of Cancer

Fitness: Exercise Programs for Patients and Survivors (Fireside Press-Simon

& Schuster 2004) and Exercise for Breast Cancer (DSW Fitness 2017)

also knows firsthand the challenges and rewards of exercising during and after

cancer treatment: She was diagnosed with lymphoma during her last year of

nursing school, in 1986, and found relief from fatigue by training as a

cyclist. It was this—and her observations in the bone marrow transplant unit

where she worked—that inspired her to pursue advanced degrees studying the link

between exercise and cancer recovery.

“At the

time, only one study had been conducted on that, and exercise professionals

were not sure that exercise was such a good thing for cancer patients,” she

says. “Today, compelling research from literally thousands of studies has

demonstrated the beneficial effects of exercise for cancer survivors—reduced

fatigue, improved quality of life and improved functional ability (muscle

strength and aerobic function).”

Like

Leonard, Schwartz thinks that it is essential for exercise professionals who

want to work with this population to pursue a solid education in the finer

points of cancer, its treatment and its effects on the body, both short- and

long-term. “I look at it like a mathematical equation,” says Leonard. “A is

surgery, B is treatment, C is side effects, D is lymphedema—add in assessments

and personal goals and, only then, can you put together a safe exercise

program.” These elements are covered in brief here, but Leonard adds, “What

people need to walk away with [after taking this CEU course] is the knowledge

that it’s not enough.”

That

said, these experts offer preliminary information to provide a glimpse into

this world so fitness professionals can decide whether this is where their

passion lies. The remainder of this article will focus more narrowly on the

side effects, treatments and considerations for people with breast cancer,

which is currently the most prevalent type in the United States (NCI 2019).

Breast Cancer Treatment and Side Effects

The most common forms of treatment for breast

cancer are surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Surgery is used

to remove cancerous tissue. The procedure can involve a lumpectomy

(removal of a small confined tumor) or a mastectomy (removal of part or

all of the breast tissue and probably some nearby lymph nodes). Chemotherapy

and radiation therapy are used to kill or slow the growth of cancer

cells with medication (IV or oral) or high-energy radiation (as from X-rays),

respectively. Radiation therapy is often used after surgery to kill any

remaining cancer cells, though it can also be used to control cancer that has

metastasized (spread from the initial site).

Other types of medication may also be used to hamper the

growth or spread of cancer, such as those that prevent or limit the production

or circulation of estrogen and those designed to help the immune system fight

cancer cells (ACS 2016; Schwartz 2017). Cryosurgery, hyperthermia, stem cell

transplant, transfusion, ultrasound, and use of radio frequency or electrical

current (to disrupt tumor cells) are just a few of the other treatments being

used to treat a variety of cancers (CETI 2019). Each of these treatments can

result in side effects, which may be different from person to person. Here are

some examples worth noting:

Medication, Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy Side Effects

Medications, including

chemotherapy, can cause or worsen digestive problems (constipation or nausea),

mouth sores, osteoporosis (bone loss), peripheral neuropathy (loss of sensation

in the hands and feet), sarcopenia (muscle loss/wasting), sleep problems and

weight gain (plus its associated risks, such as heart disease and diabetes).

“You really have to look up each treatment/medication,”

says Leonard. “Each has different side effects, from cataracts to cervical

cancer to second cancers. It’s so vast.”

Radiation therapy can cause its own set of problems. “Fatigue and skin breakdown are the primary side effects of radiation therapy that impact exercise,” says Schwartz. “Fatigue is actually reduced with a well-crafted exercise program, but skin breakdown may limit exercise because one does not want to perspire in the area that is being treated. This would cause pain and increase risks for infection.” Radiation can also cause lymphedema—swelling of the treated area from damage to the lymphatic vessels and nodes.

Both

radiation and chemotherapy can lower the body’s immune response, putting people

at risk for infection and contagious illnesses (Schwartz 2017).

Surgery Side Effects

Surgeries can cause many types of muscular

dysfunctions and compensations, some of which are not modifiable with exercise.

For example, surgical damage to the long thoracic nerve can cause the serratus

anterior (integral to pushups and proper posture) to temporarily cease firing;

this can result in a permanently retracted or winged scapula, impinging

shoulder flexion movement. Scar tissue from surgery (and radiation) can lead to

a “frozen” shoulder. With breast cancer, range-of-motion limitations primarily

restrict the nearby shoulder, though the entire body can be affected because of

the kinetic chain and the interrelation of all of the body’s systems to one

another.

Lymphedema

For those whose surgery involves removal of

lymph nodes in the armpit area or those who have undergone external-beam

radiation therapy, there is a lifelong risk for lymphedema. Lymphedema

is a serious condition marked by swelling in the pec/lat area, arm, or hand

and/or fingers on the affected side of the body. If not treated properly,

lymphedema can result in limited movement, pain and increased risk for

infection (Schwartz 2017).

Without

treatment and the proper use of a compression sleeve, lymphedema can also

progress to more advanced stages, notes Leonard. “If a person with this risk

does too much exercise (cardio, resistance training, even holding a yoga pose

for too long) and/or progresses too quickly—not knowing what the lymphatic

system can handle—lymphedema can happen,” she says. “It can completely be

avoided, but often the doctors don’t even talk about it, so the client may not

know about this risk.”

Note:

Maintaining healthy levels of body fat can help prevent lymphedema, as can

specific types of exercise. In addition to doing low- to moderate-intensity

cardiovascular exercise to improve weight and body composition, there are specific

moves that can encourage lymph drainage from the upper body. These include

pelvic tilts, modified situps and neck stretches, as well as shoulder exercises

such as shrugs, rolls, circles and isometric shoulder blade squeezes (CETI

2019). Other movements are contraindicated: For example, trainers must never

apply direct pressure to—or allow the client to place an elastic band

on/around—the affected area. (This applies to foam rollers, too.) All of this

detail serves to highlight the scope of information necessary for fitness

professionals to create a well-constructed program for the cancer survivor.

Breast Reconstruction Side Effects

Another type of surgery—breast

reconstruction—is also likely to affect exercise. For example, sometimes

“flaps” of tissue (muscle, blood vessels, fat and skin) are moved to the breast

area from other parts of the body. These include the lower stomach (TRAM flap),

back (lat flap) or buttocks (gluteal flap) (Schwartz 2017). The “shifted”

muscles, if they are still attached at their original point of origin, will

continue to behave as they always did, which can seriously disrupt specific

exercise movements, Leonard explains. For example, when the latissimus dorsi is

used in breast reconstruction, it will still fire in response to lat exercises,

even though the tissue flap is now on the anterior (front) of the body. Another

effect of this surgery can be limited shoulder ROM. Further, clients who have

undergone an abdominal TRAM cannot (and should not) perform any type of crunch

exercise; instead, they should work on shoulder stabilization (but avoid

exercises like the lat pulldown). Also, when skin expanders are in place,

clients cannot perform any exercises involving the pectoral muscles. That includes

back exercises, because the eccentric movement will stretch the chest muscles

(Schwartz 2017).

Assessing a Client With Breast Cancer

As is evident from these examples, working with a client who is undergoing or recovering from breast cancer treatment presents a myriad of challenges not often seen in the general population. Furthermore, no two cancer patients are alike; even if they have similar demographics, physical characteristics, treatment programs and so on, their individual responses to treatment may be completely different. In fact, the uniqueness of each client is the reason the NASM personal training certification is emphatic in stating that every client relationship should begin with an intake interview and assessments, including, of course, when the client has (or has had) cancer.

According

to NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training (Jones & Bartlett

Learning 2018), people with cancer can be assessed with many of the methods

recommended for general-population clients. However, when cancer is involved,

the client’s ability level and current symptoms and side effects should be

taken into consideration beforehand (NASM 2018). For example, if the person has

peripheral neuropathy in the feet, it may not be safe to do a single-leg

balance assessment, since this condition increases the risk of falling.

The

following assessments and evaluations from the NASM-CPT textbook should be performed

prior to working with a cancer survivor or current patient, with a few caveats

noted below:

- Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q)

- medical history (This includes cancer surgeries, medications and side effects, as well as other past injuries, surgeries, comorbidities and medications.)

- body composition (Don’t use a caliper on the affected area.)

- static postural assessment

- overhead squat assessment

- pulling assessment (standing cable row) (Don’t use if skin expanders are in place.)

- 6- or 12-minute walk/run test

Other

assessments relevant to cancer patients may include evaluations for pain,

fatigue, attitude and exercise history, as well as more specific moves from NASM

Essentials of Corrective Exercise Training (Jones & Bartlett 2014). The

latter include tests for upper-extremity abduction, rotation and shoulder

flexion and goniometric measurements of shoulder flexion, extension, abduction,

and internal and external rotation.

Maximum heart rate should not be used, either in initial assessments or in gauging the client’s exercise intensity or tolerance for workouts happening during active chemotherapy treatment. Often, anemia caused by chemotherapy can lead to inaccurate estimates (Schwartz 2017). (See “Intensity,” below, for more appropriate methods.)

Obtaining a Medical Release

“In an ideal world, medical providers would

work collaboratively with fitness professionals to optimize the cancer

survivor’s health,” says Schwartz. But fitness professionals should know that

the vast majority of cancer survivors can exercise without a medical provider’s

“release to exercise.” Cancer survivors with multiple comorbid conditions,

however, should consult their medical provider before beginning an exercise

program (Schwartz 2017).

Knowing

when to obtain a release, says Leonard, is another example of the importance of

being appropriately trained—for the sake of both liability and sensitivity.

“Without suitable training, you could hurt somebody who is already suffering,”

she says. “These people’s lives have been turned upside down physically,

emotionally, financially. I’ve turned down cardiac patients because I do not

consider myself an expert in that. You have to know your limitations as a

trainer.”

Basic Program Guidelines

When designing exercise programs for breast

cancer survivors, fitness professionals must maintain a degree of adaptability,

as clients’ needs and abilities will likely vary from session to session or

even minute to minute. Needs will also be different for those in treatment

versus those who are in early recovery from treatment or have been cancer-free

(or disease-stable) for a long period of time. That said, here are some

generalities that demonstrate how programming for people with cancer may differ

from what is appropriate for the general population.

Goal Setting

A recent study demonstrated that exercise

outcome expectations are often important to breast cancer survivors and so may

increase their motivation to work out (Hirschey et al. 2019). Clients may want

to lose weight, improve body composition, manage side effects and related

issues (like stress and depression), increase ROM, regain functional abilities

for everyday tasks, return to sport, or even become stronger than they were

before their diagnosis.

Keep in

mind that recovery can be particularly mentally challenging for people who were

very athletic prior to cancer treatment, so part of your role may be providing

them with enough guidance to prevent them from overtraining and causing further

injury or lymphedema. “We want two things from an exercise session,” says

Leonard. “One, for the person to leave excited to come back, and, two, we want

them to feel better than when they walked in the door.”

Mode

Research shows that aerobic exercise affords more benefits to cancer survivors than resistance training and other modalities; however, because of the increased risk of osteoporosis for many of these clients, strength training (specifically bone-building exercises) should also be encouraged (Schwartz 2017). Here, a few additional observations:

CARDIORESPIRATORY EXERCISE. Schwartz recommends beginning with walking, “as it is key to remaining functionally independent, doesn’t require supervision and has few barriers” (Schwartz 2017). Other good aerobic training options include stationary cycling, indoor rowing, low-impact or step aerobics, circuit-style group classes, and balance- or core-training classes (NASM 2018; NASM 2014).

RESISTANCE TRAINING. It is important to begin strength training with body weight—and isometrics, when appropriate—and progress the client through the NASM Optimum Performance Training™ model, beginning with Stabilization Endurance. Clients should not go beyond Phases 1 and 2 unless cleared to do so by a physician (NASM 2018). Also consider the types of moves and equipment used: Fatigue, weakness and peripheral neuropathy can make it dangerous for clients to work with free weights such as dumbbells or even with exercise bands (which they might let go of inadvertently). Even some body-weight exercises are not recommended; for example, pushups are contraindicated because of the pressure they put on the affected limb (and the likelihood that the client already has upper crossed syndrome).

STRETCHING AND FOAM ROLLING (OR SMR). Flexibility moves, including static and active stretching, may be beneficial, as long as you keep in mind any physical limitations (NASM 2018). Self-myofascial release should be avoided if a participant is undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy or is at risk for lymphedema. Also, foam rolling should never be done near a healing surgical wound, an area of lymph node removal or irradiation, or any painful or swollen body part.

OTHER MODALITY CONSIDERATIONS. Each type of exercise must be carefully evaluated to ensure that it does not pose an additional risk to the client. The risk may not always be obvious or evident without careful consideration or further instruction. Swimming, for instance, can be a great choice for breast cancer survivors with lymphedema, but only if the workout takes place in a private, chlorinated pool—and the person does not have skin damage from radiation therapy. Swimming in a public pool, river, lake or ocean is not recommended for anyone who has a compromised immune system.

Frequency

Cardiorespiratory training is advised 3–5

days per week. Resistance training is recommended 2–3 times per week (1–3 sets

of 10–15 reps or to fatigue), with 2 rest/recovery days between bouts (Schwartz

2017; NASM 2018).

Intensity

Fatigue is one of the most prevalent side

effects of breast cancer and its treatments. It is vital to strike a balance by

helping clients “push” themselves to exercise without letting them push so hard

as to worsen fatigue. Fitness pros should also discuss hydration and sleep

hygiene, as problems with these can worsen fatigue (Schwartz 2017).

Generally,

moderate intensity is recommended for people in cancer treatment or early

recovery. As mentioned earlier, peak maximal heart rate is a poor indicator for

those undergoing chemotherapy. Instead, the Karvonen method, based on heart

rate reserve, should be used to calculate MHR because this formula takes into

account resting heart rate, which is often elevated during cancer treatment.

Rating

of perceived exertion, or the Borg Scale, may also be used (Stefani, Galanti

& Klika 2017). RPE is particularly helpful for breast cancer patients,

whose fatigue and pain levels may vary (Schwartz 2017). An even simpler (yet

effective) choice is the talk test; the client should be able to carry on a

conversation during moderate exercise. Details on these methods can be found in

NASM 2018.

Duration

Assessments—both at the initial intake and in

weekly sessions—should guide the duration of activity. Some clients may need to

begin with a few minutes of low-intensity cardio training (such as slow

walking) and gradually progress to 20- or 30-minute sessions over the course of

several weeks. For those struggling with fatigue, the recommended 30 minutes of

cardio can be divided into two or three 10-minute sessions (or five or six

5-minute sessions), done at times of the day when energy levels are highest.

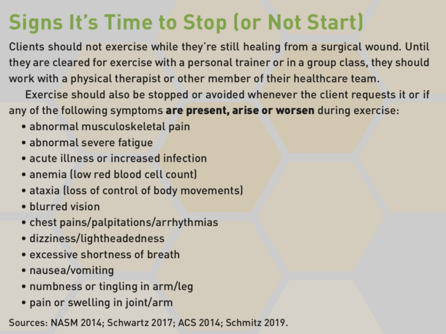

Group exercise instructors should be sure to tell participants with cancer to take rest intervals as needed and not try to “keep up” with the class; they should also know it is fine to leave at any point and, in fact, they should absolutely stop in certain circumstances (see “Signs It’s Time to Stop").

Progression

Clients should be progressed slowly—using the

NASM OPT™ model—from stabilization to strength. They should not perform

plyometric training until they can complete three Phase 1 workouts per week

(NASM 2018); some clients may remain in corrective exercise for many weeks, if

not permanently.

As

clients become able to do more, fit pros can progress them first by lengthening

or adding exercise sessions, then by gradually increasing the intensity or

difficulty (NASM OPT phase). More extensive certification courses, such as those

from CETI, offer detailed guidelines on the return-to-exercise timing and

progressions for a number of specific cancers.

Location and Equipment

For clients with a compromised immune system,

it can be dangerous to participate in group exercise or work out at a gym,

where bacteria and viruses can abound. Helpful precautions for clients include

wearing exercise gloves, using their own water bottle (not a fountain), wiping

down machines and equipment before use as well as after, and scheduling

training during “slow” times at the gym—or shifting workouts to the home.

Fitness professionals who are not feeling well or suspect they may be getting

sick should never train a person with cancer.

Finally,

for this population (and anyone with balance concerns, peripheral neuropathy,

and/or increased risk of bleeding or bruising), the workout area must be kept

clear of obstacles to prevent inadvertent collisions or other injuries (such as

bumping into another exerciser, dropping free weights or getting blisters from

improper footwear). Also, fitness pros should check equipment for any burrs or

imperfections that could cause cuts or other skin damage.

Frame of Mind and Motivation

Last but not least, breast cancer treatment

and side effects have a significant impact on the mind as well as the body.

“Breast cancer is one of the most outward cancers,” says Leonard. “It affects

the woman’s self-esteem, her control of her body, her sense of womanhood.”

Leonard advises giving sincere praise and helping clients focus on how far they

have come by comparing progress to initial assessments.

Some

people will want to talk about their cancer and treatment; others will not.

Elite athletes and fit pros may need extra encouragement, as they are more

likely to backslide in strength than less-fit patients who are just beginning

to work out and may actually see progress almost right away.

“You

may need to be part friend, part cheerleader, part exercise physiologist,” says

Leonard. “And you have to keep negativity from rubbing off on you. It’s not

always fun, but it is incredibly rewarding.”

The Rewards of Working With Clients Who Have Cancer

“Cancer strips you of everything,” says

Leonard. “We have the power to give these clients some kind of control at a

time when their body has completely failed them. I can’t think of a situation

where I couldn’t help someone with cancer.”

As

anecdotal evidence of the possibilities, Schwartz shares her own success story:

After her diagnosis and during treatment, she experienced weight gain,

depression and exhaustion. “Just walking up a flight of stairs took effort,”

she says. “I started cycling and slowly built my endurance up enough to ride

with a group that was training in town. Little did I know that many of these

cyclists were Olympic team members and professional racers.” Schwartz began

racing—then winning. She went on to set several world records and won a

national tandem time-trial championship.

The

beauty of learning more about working with this population is that many of the

lessons can be applied to many modalities and many different people with many

types of conditions. “Once you

understand how to program for people with cancer, you can adapt [that

knowledge] to any modality: TRX®, Pilates, anything,” says Leonard. “But you

have to understand the theory, how to identify when something is not going

right and how to keep the client safe.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: You can request a free copy of “Essentials of Cancer Exercise” and learn more about the Cancer Exercise Specialist Advanced Qualification, Breast Cancer Recovery BOSU® Specialist™ Advanced Qualification and Cancer Exercise Pilates Specialist® Advanced Qualification by visiting thecancerspecialist.com.

To earn 0.2 AFAA/0.2 NASM CEUs, purchase the CEU quiz here ($35) and successfully complete it online.