Here’s what happens behind the scenes to bring new ideas to market.

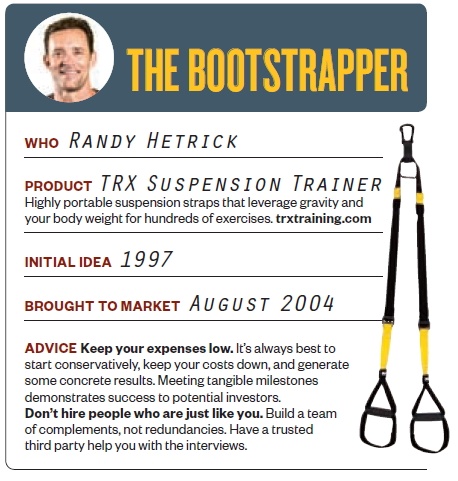

Seventeen years ago, while deployed on a counter-piracy mission in Southeast Asia, Navy SEAL Randy Hetrick stumbled upon his big fitness idea. Looking for a way to keep his squadron fit in a featureless warehouse, he sewed a jujitsu belt to parachute webbing, threw the straps over a door, and used it to perform rows, pull-ups, and other exercises using his body weight. When he left the SEALs four years later, Hetrick put himself through Stanford business school, earning an MBA. He continued refining his device and founded a company. It’s now a decade later and his company, TRX Training, has grown into a $50 million per year global business.

Of course, it wasn’t easy growing TRX, and Hetrick’s story is anything but ordinary. Far more common are the fitness products that flop, flame out, or—even worse—fail to launch in the first place. That’s because it’s hard to turn a good idea into a concrete product, and bringing it to market is even harder still. To help you wrap your head around it, we talked to five fitness professionals who’ve traveled that rocky territory already. Then we put together this quick-and-dirty step-by-step plan to bring your idea to market. Follow it, and work harder than you’ve ever worked before, and maybe you’ll succeed and share your story with us someday.

Step 1: Have a Good Idea

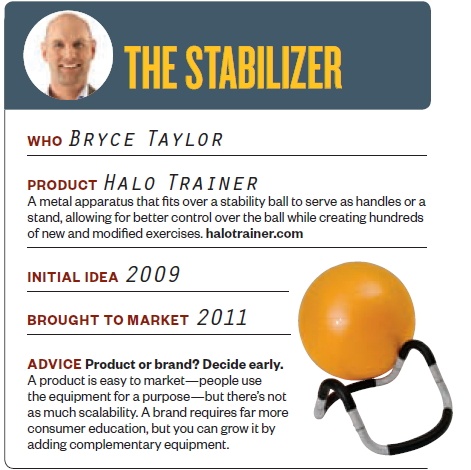

It all starts with an idea that fills a need. For Indianapolis-based physical therapist Bryce Taylor, the idea was to give the classic stability ball added variability for use in core strength training. “I felt that a stability ball offers too much instability to progress loads and movements,” he says. His solution was the Halo Trainer, a metal apparatus that fits over a stability ball and serves as handles or a stand to better control the ball, opening the door to hundreds of new and modified exercises. Today, he’s licensed the Halo Trainer to Merrithew Health & Fitness, the company behind Stott Pilates, Zen-ga, and Total Barre.

Step 2: Prototype

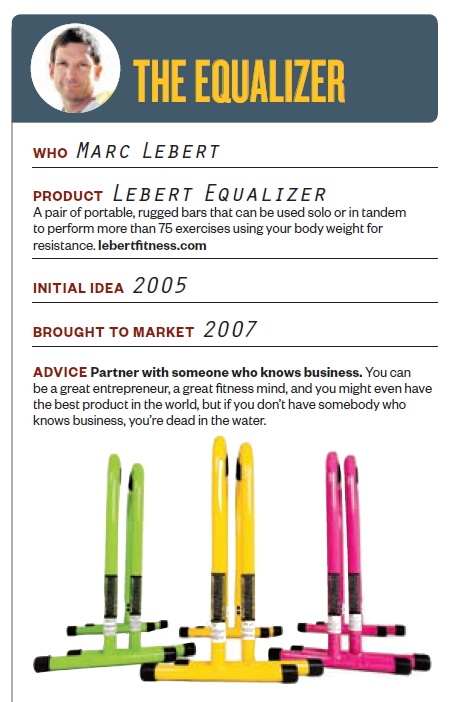

Now it’s time to turn your fitness-tool idea into reality. This is the mad-scientist stage, where it helps to be handy with tools (or know someone who is) and have a mechanical mind. For Marc Lebert, the inventor of the Lebert Equalizer, what started as tinkering with scrap steel and a welder over a case of beer turned into eight months of prototyping. “We wanted to get the design right—one height that kind of fits all—and make sure we had a product that would stand up to abuse,” he says. From the first rusty unibody hunk of steel, they eventually developed the more versatile design of separate bars whose width could be adjusted for dips, pull-ups, and push-ups.

Step 3: Market-Test Your Product (Steps 3, 4, and 5 are interchangeable, depending on how you develop your business.)

There are a number of ways to test your concept, but the most important thing is that you do it. Get it into the hands of unbiased third parties, people who you think may constitute your likely audience. That’s what personal trainer Derek Mikulski, the inventor of the ActivMotion Bar, learned early on. After making roughly 100 prototypes of his product—an unstable, weighted bar that’s similar to a PVC slosh pipe but with smoother instability caused by steel balls rolling back and forth inside—he brought them into the Life Time Fitness where he was working in Troy, Mich. “I put them in the hands of other trainers and their clients,” Mikulski says, “to get unbiased feedback.” The positive reactions of colleagues and clients are what pushed him to keep pressing forward.

Another place to vet your idea—only after you’ve applied for a patent (see Step 5)—is a trade show. Each of the five inventors we spoke with tested the waters at one or more major fitness trade show, in particular at IDEA World and IHRSA (International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association). “It was great validation,” Mikulski says of IHRSA, “and we linked up with some buyers and customers who we’re still doing business with today.”

Step 4: Seek Partners and/or Funding

Launching a product is a huge time investment requiring full personal commitment. “You need to do demos and go to trade shows,” Lebert says, which can lead to few days off and lots of time away from your family. And, of course, there’s the money. “You’re going to need solid financing, six figures minimum,” says Lebert.

This is why you need to find a partner or investors. There’s no right or wrong way to fund a product, but perhaps the best way to do it is to get your product in the hands of your professional network, including clients and other trainers. “Potential investors really need to understand and believe in your product,” Taylor says. His initial funding came from two patients who’d worked with his Halo Trainer prototype during physica

l therapy. They experienced how well the product worked and had confidence in Taylor’s vision. (Mikulski was funded by clients too.)

Anthony Carey on the Core-Tex

Anthony Carey on the Core-Tex

Another important consideration is finding someone who has product experience and is business-savvy. When personal trainer and fitness-studio owner Anthony Carey wanted to build the Core-Tex—a versatile reactive training platform—he partnered with Olden Carr, a mechanical engineer with extensive experience in product design as well as the nuts-and-bolts work of sourcing and working with manufacturers. “It would’ve been a tremendously challenging learning curve had one of us not already had that experience,” Carey says.

Step 5: Protect Your Idea

Your invention could become the next TRX, but you need to establish it as your own to see any of the financial rewards, or an existing company could take it and bring it to market first. Talk to (and hire, if necessary) an intellectual property lawyer to see if a patent is needed, and to discuss next steps. Those steps might involve applying for a relatively inexpensive provisional patent to give you time to complete the complicated (and costly, when you add lawyer fees) utility patent application. Depending on the level of market testing you settle on and where you look for investors, you may want to apply for a patent earlier in the process (Step 3, for example).

Taylor suggests applying for a design patent as well, to protect your invention during the two to five years it takes to issue a utility patent. “If you waited for the utility patent,” Taylor says, “you couldn’t take any action if someone was to infringe upon your invention.”

Step 6: Manufacture It

This isn’t as simple as it sounds. Taylor took his Halo Trainer prototype—a sand-filled soldered copper tubing bent around a basketball hoop and wrapped in foam and tape—to a stability ball manufacturer in Colorado, where it quickly deformed. “They said, ‘Come back when you have a better prototype,’ ” he says, laughing. Mikulski hired a consultant with expertise in assessing factory operations to shop around for a qualified manufacturer for the ActivMotion Bar, and found success in a local, Michigan-based factory. “The manufacturing and fulfillment happens right outside of Detroit,” he says. “To stay efficient, we keep all production and shipping under one roof, right in our own backyard.” As for Lebert, he started with a Canadian factory, then switched to an Asian one. Wherever you go, be sure to provide a meticulous accounting of your invention’s size, shape, weight, color, and any other qualities the factory needs to know in order to manufacture it exactly as you intend.

Step 7: Sell, Sell, Sell!

Congratulations, you’ve got a viable fitness product. Now the sales work begins. “Getting the product to market is the first step,” says Carey. “If you’re not marketing and doing sales, then you’ve got a garage or warehouse full of product that nobody knows about, no matter how good it is.” Go to trade shows and connect with trainers, gyms, and other fitness professionals. If you can win them over to your invention, they’ll become your best ambassadors.

Did you know? NASM fitness professionals receive SPECIAL discounts on some of

the most premier health and fitness products in the industry, including 3 of these highlighted products. Log into your NASM customer account to access details.

By Peter Koch, NASM's The Training Edge, July/August 2014