Originally appeared in the 2016 summer issue of American Fitness Magazine.

Originally appeared in the 2016 summer issue of American Fitness Magazine.

Shoulder pain is the most common complaint among swimmers, both competitive and recreational, with prevalence ranging from 40 to 91%.1 This is partly due to the repetitive nature of the sport, since a competitive year-round swimmer may perform 11,000 yards per day resulting in 30,000 shoulder rotations per week.2

The frequency of anterior shoulder pain during and after workouts among swimmers has led to the term “swimmer’s shoulder.” Generally, the condition has a gradual onset, but can be caused by multiple factors. This article will discuss how imbalances occur and impact the development of swimmer’s shoulder, plus corrective exercise strategies to help prevent or improve it. Muscle Movement

the Muscles responsible for swimming

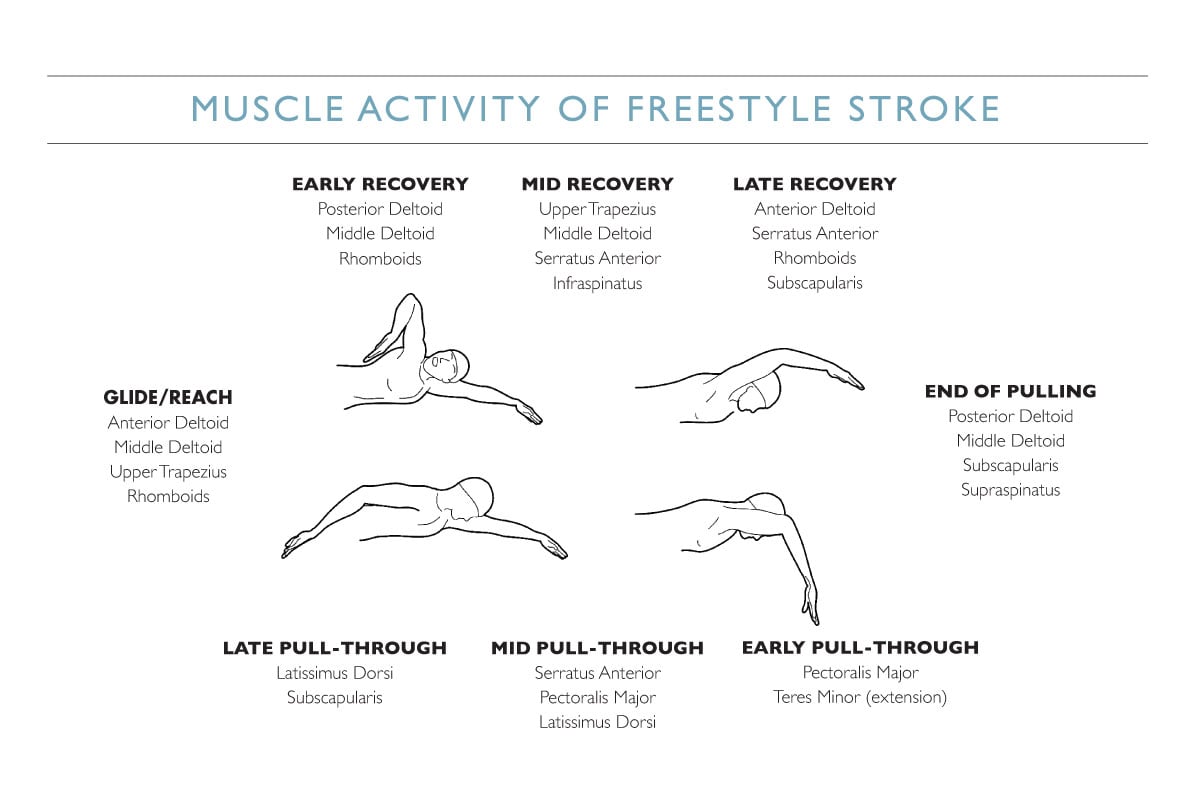

To understand key causes for this condition, it’s important to identify what muscles are responsible for the swimming stroke. Focusing on freestyle, since it’s the most common and research supported, it can be broken into two primary phases.

The first phase is known as the pull-through where propulsion occurs and is further divided into subphases depending on hand relationship to the water. This is followed by the recovery phase when the hand is out of the water.

During each phase all the muscles of the shoulder complex, including the latissimus, deltoid, rotator cuff, pectoral and scapular stabilization muscles, must synergistically work together propelling the body forward. The following chart, adapted from the book Breakthrough Swimming by Cecil Colwin, describes the interaction of each muscle during the swimming stroke.

When a swimmer experiences pain, their stroke movement will be altered with some muscles being inhibited while others are recruited as a compensatory mechanism. If inadequate or no rehabilitation has been performed, the impaired motor control patterns will persist even after pain has resolved, continuing to alter swim mechanics.

The sequela of the dysfunctional movement patterns will result in muscular imbalances changing the muscle length-tension ratios, leading to even more dysfunctional movement. This pattern can last indefinitely until faulty movements are corrected. Two main regions affected are the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers.

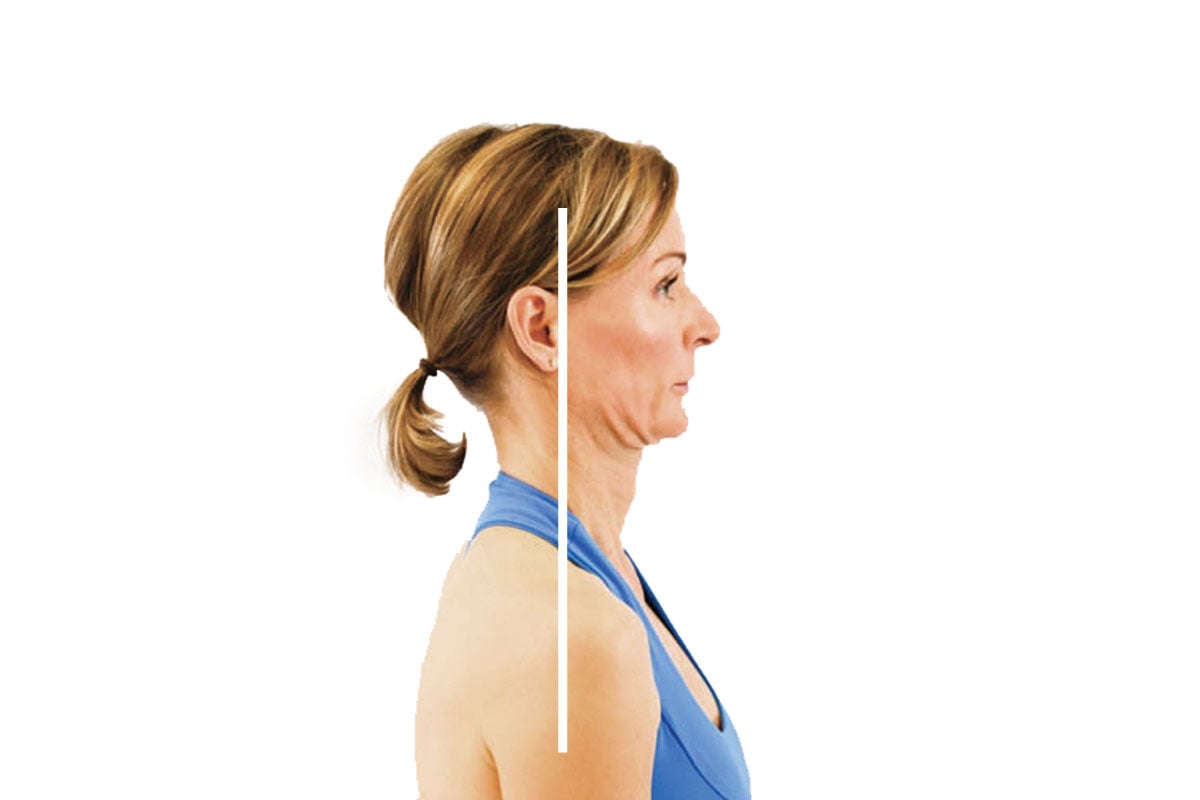

Performing an active assessment with range of motion is important for all overhead athletes A static posture assessment should also be performed as part of a baseline evaluation. If an athlete is experiencing swimmer’s shoulder, they will likely have postural misalignments including forward head, rounded shoulders, scapular winging, or right to left muscular imbalances.

Normal Sagittal Posture

Normal static posture provides a foundation from which the extremities function. Therefore, any structure with a weak foundation leads to secondary problems elsewhere in the system. More specifically for swimmers, a change in scapula position increases the likelihood of shoulder impingement problems in addition to restricted neck movements and excessive muscle loading.

In order to assess a client’s true posture and avoid the Hawthorne effect,9 have clients take a couple of steps in place and nod their head with their eyes closed. Have them stop, keeping eyes closed, and assess their posture from both front and side views. By keeping their eyes closed, the righting reflex (which corrects body orientation in an upright position) will be avoided, allowing a more accurate assessment.

If there is a postural fault related to forward head, Harman and colleagues found a simple exercise program could improve postural alignment.10 Study participants performed two strengthening and two stretching exercises consisting of chin tucks and shoulder retraction exercises coupled with a cervical extensor and pectoralis stretch.

Head Retraction Exercise

Looking forward with shoulders back, activate core muscles to provide stability and minimize trunk sway. Attempt to draw head directly backward, keeping it level—avoid tilting head up or down. Hold for two seconds, return to start position, repeat. (3 sets, 10 reps)

Blackburn "T"

This posterior shoulder strengthening exercise was shown to elicit high EMG activity of the infraspinatus, teres minor and trapezius muscles.13 Start by lying on a ball, lower body in plank position, arms extended in front at shoulder level. Make hands into soft fists, thumbs up. Lift the arms as if moving them behind, keeping elbows straight. Squeeze shoulder blades together while trying not to extend the head. Hold for three to five seconds, return to start position, repeat. (3 sets, 10 reps)

Supine Chest Stretch

Lie on a foam roll, supporting head and running along the spine to the pelvis, feet flat on floor. Bend both elbows to 90° at shoulder level with palms facing up. Relax, feeling a stretch in the chest and anterior shoulder. Maintain for 30 to 60 seconds.

Do not force arms to the floor. Keeping elbows bent will also stretch pectoral muscles instead of the anterior capsule of the shoulder joint. Rounded shoulders is another common postural fault among swimmers.11 Kluemper and colleagues performed a six-week anterior stretching and posterior strengthening shoulder program, concluding that stretching the internal rotator and adductor muscle groups and strengthening the external rotator and abductor groups can reduce this posture in competitive swimmers.12

Push-Up Plus

Rounded shoulder posture and poor scapular control can also be due to serratus anterior weakness. Wadsworth and colleagues demonstrated a significant delay in serratus anterior activation in the painful shoulders of swimmers, resulting in an inability to stabilize the scapula against the thoracic wall causing scapular winging or scapular dyskinesia.14 A push-up plus is an effective intervention in strengthening the serratus anterior muscle.

According to Decker et al., a push-up plus on the knees was more user friendly than the traditional push-up plus using less force, but eliciting similar electromyography (EMG) ampltudes.15

Start in the push-up position with knees or toes (advanced) touching floor, hands under shoulders. Maintaining a plank position, lower toward floor, followed by a push-up. Then push the upper back higher so shoulders are in a rounded, protracted position. Return upper back to neutral plank position and repeat.

Swimmer's Shoulder Exercise Programming

It’s important that clients with existing shoulder pain are cleared by their physicians before starting an exercise program. If the client has completed physical therapy, you can use the exercises they learned as a starting point and base for progression.

- General guidelines for clients with previous or existing shoulder pain:16Never exercise through pain.Groove appropriate and perfect motion and motor patterns before adding load or other challenges.Begin by taking gravity out of the equation; start supine or prone and progress to quadruped, kneeling then standing.Increase intensity or time, but not both. (Intensity can be increased by either changing resistance or stability.)

- For clients ready to progress, the following guidelines will help do this safely and effectively:17If still making progress, continue with the current workload.If plateaued, progress at a 2 to 10% increase.If experiencing a flare-up, decrease volume.

As with all exercise programs, long-term adherence and regular exercise execution are important to achieve satisfying results. For more shoulder programming strategies, check out NASM’s Corrective Exercise Specialization.

For a comprehensive look into the corrective exercise continuum, here’s a handy resource.

REFERENCES:

- BAK, K. “THE PRACTICAL MANAGEMENT OF SWIMMER’S PAINFUL SHOULDER: ETIOLOGY, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT.” CLINICAL JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, 20, NO. 5 (SEP 2010): 386-90.

- BEACH, M.L., WHITNEY, S.L. AND DICKOFF-HOFFMAN, S. “RELATIONSHIP OF SHOULDER FLEXIBILITY, STRENGTH, AND ENDURANCE TO SHOULDER PAIN IN COMPETITIVE SWIMMERS.” THE JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC AND SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPY, 16, NO. 6 (1992): 262-68.

- HEINLEIN, S. AND COSGAREA, A.J. “BIOMECHANICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE COMPETITIVE SWIMMER’S SHOULDER.” SPORTS HEALTH, 2, NO. 6 (NOV 2010): 519-25.

- NIJS, J., ET AL. “NOCICEPTION AFFECTS MOTOR OUTPUT. A REVIEW ON SENSORY-MOTOR INTERACTION WITH FOCUS ON CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS.” THE CLINICAL JOURNAL OF PAIN, 28, NO. 2 (FEB 2012): 175-81.

- WARD, S., ET AL. “ROTATOR CUFF MUSCLE ARCHITECTURE: IMPLICATIONS FOR GLENOHUMERAL STABILITY.” CLINICAL ORTHOPAEDICS AND RELATED RESEARCH, NO. 448 (JUL 2006): 157-63.

- GRIEGEL-MORRIS, P., ET AL. “INCIDENCE OF COMMON POSTURAL ABNORMALITIES IN THE CERVICAL, SHOULDER AND THORACIC REGIONS AND THEIR ASSOCIATION WITH PAIN IN TWO AGE GROUPS OF HEALTH SUBJECTS.” PHYSICAL THERAPY, 72, NO. 6 (JUN 1992): 425-31.

- CLARK, M., LUCETT, S. AND SUTTON, B. NASM ESSENTIALS OF CORRECTIVE EXERCISE TRAINING. BURLINGTON: JONES & BARTLETT LEARNING, 2014.

- TOVIN, B. “PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF SWIMMER’S SHOULDER.” NORTH AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPY, 1, NO. 4 (NOV 2006): 166-75.

- WICKSTROM, G. AND BENDIX, T. “THE ‘HAWTHORNE EFFECT’—WHAT DID THE ORIGINAL HAWTHORNE STUDIES ACTUALLY SHOW?” SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF WORK, ENVIRONMENT & HEALTH, 26, NO. 4 (AUG 2000): 363-67.

- HARMAN, K., ET AL. “EFFECTIVENESS OF AN EXERCISE PROGRAM TO IMPROVE FORWARD HEAD POSTURE IN NORMAL ADULTS: A RANDOMIZED, CONTROLLED 10-WEEK TRIAL.” THE JOURNAL OF MANUAL AND MANIPULATIVE THERAPY, 13, NO. 3 (JUN 2005): 163-76.

- LYNCH, S., ET AL. “THE EFFECTS OF AN EXERCISE INTERVENTION ON FORWARD HEAD AND ROUNDED SHOULDER POSTURES IN ELITE SWIMMERS.” BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, 44, NO. 5 (APR 2005): 376-81.

- KLUEMPER, M., ET AL. “EFFECT OF STRETCHING AND STRENGTHENING SHOULDER MUSCLES ON FORWARD SHOULDER POSTURE IN COMPETITIVE SWIMMERS.” JOURNAL OF SPORT REHABILITATION, 15, NO. 1 (FEB 2006): 58-70.

- ESCAMILLA, R., ET AL. “SHOULDER MUSCLE ACTIVITY AND FUNCTION IN COMMON SHOULDER REHABILITATION EXERCISES.” SPORTS MEDICINE, 39, NO. 8 (2009): 663-85.

- WADSWORTH, D. AND BULLOCK-SAXTON, S.E. “RECRUITMENT PATTERNS OF THE SCAPULAR ROTATOR MUSCLES IN FREESTYLE SWIMMERS WITH SUBACROMIAL IMPINGEMENT.” INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, 18, NO. 8 (NOV 1997): 618-24.

- DECKER, M., ET AL. “SERRATUS ANTERIOR MUSCLE ACTIVITY DURING SELECTED REHABILITATION EXERCISES.” AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, 27, NO. 6 (NOV-DEC 1999): 784-91.

- ADAPTED FROM BLOG BY ED LECARA, PHD, DC, MBA, ATC, CSCS.

- AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SPORTS MEDICINE POSITION STAND. “PROGRESSION MODELS IN RESISTANCE TRAINING FOR HEALTHY ADULTS.” MEDICINE & SCIENCE IN SPORTS & EXERCISE, 41, NO. 3 (MAR 2009): 687-708.