Chances are, at some point in your personal training career, you will work with clients who’ve had a knee replacement or are on track to get one. This can be a daunting prospect to consider, but it doesn’t have to be. With a combination of cultivated expertise, connections with allied medical professionals and a progressive approach, you can deliver a methodical program that can get these clients back on their feet again.

Also known as knee arthroplasty, knee replacement surgery involves cutting away damaged bone and cartilage and replacing them with an artificial joint “made of metal alloys, high-grade plastics and polymers” (Mayo Clinic 2017). According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS 2019), more than 600,000 knee replacements are performed annually in the United States. The American Joint Replacement Registry expects that this number will rise due to osteoarthritis and obesity (AJRR 2018); AAOS also predicts that by 2030 approximately 3.48 million knee replacements will occur annually. In short, this isn’t a challenge that’s likely to go away anytime soon.

With such a pervasive need for surgical intervention, patients need to

make sure they have enough access to services and physical therapy visits. Some

people demonstrate enough progress with objective data to achieve movement

within functional to normal ranges, allowing them to be discharged within the

prescribed number of visits.

Others are not ready to be discharged by that

time, either physically or functionally, but insurance or other financial

restrictions may force them to discontinue therapy or pay directly out of

pocket. In those cases, patients are given instructions for continuing with

their home exercise program, but many run the risk of stopping too soon because

they lack supervision and guidance. This is where a knowledgeable personal

trainer comes in.

With a clear understanding of the specific needs of people who are recovering from a knee replacement, personal trainers and specialists in human movement can program a variety of exercises and the strategic use of equipment to safely progress clients to reclaim normal joint function. These clients need to continue with individualized exercises in order to:

- increase or maintain strength and stabilization;

- increase dynamic balance;

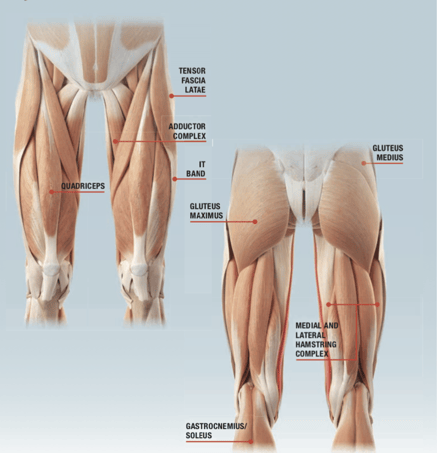

- maintain or increase latissimus dorsi, hamstring, quadriceps and gastrocnemius flexibility;

- increase cardiomuscular endurance; and

- increase ankle mobility.

A focus on the core, latissimus dorsi, hip girdle, knees and ankles, in

particular, goes a long way in helping clients get back to the way of life they

enjoyed before their knee pain began.

Read also: Exercises for Knee Pain

Knee Knowledge

The knee is a complex structure and one of the most stressed joints in

the body. This weight-bearing hinge joint comprises bones, ligaments, cartilage

and tendons and has the power to do the following:

- provide stability

- act as a shock absorber

- help lower and raise the body

- make walking more efficient when needed

- allow the leg to twist (Davis 2017)

While the following overview is not comprehensive, it provides a

snapshot of why people end up getting knee replacement surgery.

Osteoarthritis

One of the most common reasons for knee replacement surgery is to relieve the pain and discomfort caused by osteoarthritis (Mayo Clinic 2017). Not being able to comfortably walk, climb stairs, and raise or lower oneself from sitting to standing and vice versa can severely affect quality of life.

Obesity

A study published in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Derman, Fabricant & David 2014) found that knee replacements were far more prevalent among patients who had overweight or obesity. According to the study, total knee replacements more than tripled between 1993 and 2009.

Age and gender factors

Out of the estimated 4.7 million Americans who have undergone total knee arthroplasty as of 2010, prevalence is higher in women (3 million women versus 1.7 million men) (Maradit Kremers et al. 2015). Researchers at the Mayo Clinic (2019) also found that prevalence increases by age and that approximately 10% of study subjects between ages 80 and 89 had undergone a total knee replacement procedure.

Abnormal knee formation or alignment

Misalignment issues, such as “knock-knee” or “bowleg,” create an unnatural angle between the femur and the tibia (BoneSmart 2019). The effect on the knee joint can lead to degeneration of one or more of its individual components. In time, the cartilage may wear away, causing severe pain from lack of cushion between the bones.

Whatever the reason, clients who have been cleared to begin an exercise program after ending or completing a physical therapy regimen following knee replacement surgery will need a personal trainer who can pay proper attention to the finer details of the knee mechanism, as well as the body’s recovery from the procedure.

Before the First Training Session

To prevent injury - as supported by the courses in our injury prevention bundle - you need to start off strategically.

By the time clients who have had total knee replacements are ready to

start working with a trainer, they may have been sedentary for quite some time.

Prior to training, be sure to get input from the prescribing surgeon; also get

written documentation that your client has been released from the postsurgical

physical therapy regimen.

In contributing to clients’ well-rounded care, it’s important to stay

within your scope of practice, but it’s equally important to continue

communicating with the allied health professionals who were treating the

clients before they arrived at your facility. This communication allows you,

the personal trainer, to ascertain clients’ current status and abilities and

understand these in the context of goals and any necessary restrictions.

In particular, physical therapists will share clients’ continued needs

and limitations—for example, regarding flexibility, mobility, strength,

stability and balance. Apply these observations to your program design

thoughtfully, with a progressive mindset to help clients advance in their

movement and comfort levels. Personalization is key, as is paying attention to

the particular supportive anatomy clients use to compensate during the initial

adjustment period, as well as any residual pain issues as recovery continues.

Progress should pick right up from where a client left off in physical therapy.

With knee replacement clients, it’s important to understand the

underlying physical factors that caused degradation of the joint. This is

different from working with patients who needed surgery to repair a broken arm

or a torn ligament.

Anxiety and depression are possibilities whenever a person is dealing

with a debilitating, long-term mobility limitation, and these feelings can also

present during training. Always be cognizant of any co-morbidities—such as

hypertension, asthma, obesity and diabetes—that may affect exercise

programming, tolerance and participation.

Program Design Essentials

If you aren’t assessing, you’re guessing. First and foremost, you will

need to base your program on the notes and restrictions given by the referring

physical therapist or physician. When you do your own assessment, include not

only the knee, but also the surrounding joints. For future comparison, note any

assessment modifications you’ve made. The priority is to train the individual

in front of you and adhere to medical guidelines. While not exclusive or

universal, the following list identifies some important things to track (NASM

2014):

- In the overhead squat assessment, check for adduction and abduction. However, keep in mind that many people will not be able to hit the squat depth due to the replaced knee, so don’t rely exclusively on OHSA, as it could put some clients at a disadvantage.

- When you’re working on a client’s static posture, refer to the physical therapist’s notes, and observe kinetic chain checkpoints.

- Check ankle dorsiflexion, knee extension, hip extension and hip internal rotation (the physical therapist should have done goniometric measurements).

- Refer to the physical therapist’s notes on manual muscle testing, including anterior/posterior tibialis, gluteus medius and/or maximus, medial hamstring complex, and adductors.

Next, use information from the assessment and the client’s goals to

create a customized program. Taking a multijoint approach is preferable to

focusing solely on the joint that has been replaced, because the knee is part

of a kinetic chain that is greatly affected by the linked segments from the

proximal and distal joints. The foot, the ankle and the lumbo-pelvic-hip

complex all play a role in knee motion and impairment (NASM 2014).

Start training twice per week to avoid overtraining, and exercise within

a pain-free range of motion.

Additional Parameters

Ease into the workout

Extend warmup time, especially in the presence of other pre-existing conditions. Walking is a great way to safely raise the client’s core body temperature and heart rate prior to the workout.

Stress the basics

Focus on technique, form and postural alignment, and concentrate on improving cardiorespiratory endurance, which addresses co-morbidities. Since the bulk of a client’s time is spent away from training, educate the client about the program, and give homework activities. It’s critical to establish movement intelligence (the ability to understand optimal coordination) and client competence and independence with exercise performance and correction. Emphasize the benefit and rationale of exercise selection, form, risks and benefits, and proper progression, which should be gradual.

Use a variety of safe movements

There is plenty of opportunity for creativity when you’re working with this population. Some valuable programming notes:

- Establish basic functional components first, such as climbing stairs and carrying loads centrally, bilaterally and unilaterally.

- Introduce a kettlebell carry to increase the challenge and simulate an activity of daily living.

- Use developmental patterns such as quadruped, kneeling and half-kneeling (only if cleared by the physical therapist) for optimal strength, neuromuscular control and stabilization.

Be dynamic and functional

Pull from tried-and-true techniques:

- Train the major muscle groups multidirectionally using chop and reverse-chop patterns.

- Do exercises such as stepups and resisted stepups to improve endurance.

- Use dynamic patterns that incorporate multiplanar motion to integrate developmental motor patterns that more closely resemble activities of daily living, recreational sports and exercise.

- When appropriate, program closed-chain moves such as squats, a variety of lunges and modified deadlifts to emphasize stabilization and function.

- Try a circuit training format, which is a great way to include a variety of exercises that challenge the client’s endurance.

Train balance

Once static balance is mastered, begin to incorporate proprioceptively enriched surfaces and perturbations (gentle pushes in various directions). Build on dynamic balance skills by incorporating bilateral stance and single-leg stance into exercises. Following are some additional balance program elements:

- Initiate balance exercise with weight-shifting in an X pattern, followed by clockwise and counterclockwise circles; then progress to walking in those patterns on stable and unstable surfaces.

- Use a rebounder or a small trampoline for marching, weight-shifting and rocking to improve balance on unstable surfaces. Add obstacles for the client to step over or onto, and design obstacle courses to allow opportunities to master directional changes, distances and speeds; this will advance both agility and balance training.

- Incorporate vision and balance drills with exercises to progress the client. For example, have the client perform shoulder raises on an Airex® pad or while sitting on a stability ball. Do a single- or double-leg stance on a balance pad with and without visual input or with and without a mirror.

- Stabilize the spine and hips with targeted core training, which will also help with balance. Strengthen and increase postural core endurance with a variety of planks: modified, full, with an Airex pad under the forearms, side planks, TRX® planks and TRX side planks. The side planks help strengthen the latissimus dorsi and shoulder girdle, which, in addition to being important for their relationship to shoulder mobility and stabilization, also helps stabilize the spine and hips, which contributes to a healthy, functioning knee. The hips need to be mobile, flexible, strong and stable to assist with balance and fall prevention.

- Address the base of support: the lower legs. The ankles need mobility in dorsiflexion, lateral stabilization between the invertors and evertors, and flexibility in the gastrocnemius to adequately squat and provide dynamic balance. Lengthening and strengthening moves from Pilates and yoga are good options for incorporating postural control.

Progress to integration. When appropriate, add carefully and progressively instructed kettlebell

swings to fully integrate all systems. The reasoning: Mobile, strong and stable

hips are important allies for the knees and will enable the client to fully

participate in activities of daily living and recreational exercise with

optimal neuromuscular control.

A Life Well-Lived

As the population continues to live longer with a desire to remain or become active, personal trainers are more likely to encounter clients who have had knee replacements. Experienced, educated fitness professionals are ideally situated to help these people get back to an active life—where they’ll be even better prepared to travel, play sports, exercise, and remain mobile and independent.

Help Your Clients Move, Feel and Live Better

The Corrective Exercise Continuum offers a process for transformation. Arm yourself to be in the best position to help clients—with the NASM Corrective Exercise Specialization, a proven program that addresses muscular dysfunction.

The NASM-CES teaches you how to use a variety of static and dynamic assessments to identify imbalances. From there, you can design effective programs with the Corrective Exercise Continuum, a simple yet effective four-step process you can use with your clients to improve and, ultimately, correct common movement compensations.

References

AAOS

(American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons). 2019. Total knee replacement.

Accessed March 2019: orthoinfo.aaos

.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement/.

AJRR (American Joint Replacement Registry). 2018. AJRR Business Report & Plan. Accessed March 2019: ajrr.net/images/downloads/bod-org-materials/AJRR_2016-18_Busi

ness_Report_and_Plan_final-9-17-2015wAppendices.pdf.

BoneSmart. 2019. Reasons for knee replacement surgery. Accessed March 2019: bonesmart.org/knee/conditions-leading-to-knee-replacement-surgery/.

Davis, K. 2017. How to prevent and treat knee injuries. Medical News Today. Accessed March 2019: medicalnewstoday.com/articles/299204.php.

Derman, P.B., Fabricant, P.D., & David, G. 2014. The role of

overweight and obesity in relation to the more rapid growth of total knee arthroplasty

volume compared with total hip arthroplasty volume. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery,

96 11, 922–28.

Maradit Kremers, H.D., et al. 2015. Prevalence of total hip and knee

replacement in the United States. The

Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 97 17, 1386–97.

Mayo Clinic. 2017. Knee replacement. Accessed March 2019: mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/knee-replacement/about/pac-20385276.

Mayo Clinic. 2019. First nationwide prevalence study of hip and knee arthroplasty shows 7.2 million Americans living with implants. Accessed March 2019: mayoclinic.org/es-es/medical-professionals/orthopedic-surgery/news/first-nationwide-prevalence-study-of-hip-and-knee-arthroplasty-shows-7-2-million-americans-living-with-implants/mac-20431170.

NASM (National Academy of Sports Medicine). 2014. NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise

Training (Rev. ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.