What is thoracic outlet syndrome?

Are there assessments that personal trainers can consider to identify it, and can corrective exercise programming help?

What is Thoracic Outlet Syndrome?

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a condition involving the vessels of the neck, shoulder and arm. The bundle of nerves, veins and arteries - neurovascular bundle - is known as the brachial plexus. Problems arise when the brachial plexus is compressed somewhere along its journey from the spinal cord to the shoulder and arm. The exact origin of TOS is often misunderstood as the symptoms are closely related to carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).

More than half of the individuals with CTS often test positive on at least one TOS exam (Burnham, 2010), which often leads to confusion and misdiagnosis. Adding to the complexity of the situation is the fact that many suffering individuals do not know the difference between the symptoms of TOS, CTS, or what could be exacerbated shoulder impingement.

Therefore, it is important to understand that the following symptoms could be due to one of several possible upper-extremity issues.

What are the Signs of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome?

Symptoms of TOS may include:

- Muscle wasting

- Numbness and tingling in the arm, hand or

fingers - Pain in the neck, shoulder or hand

- Discoloration and swelling of the arm and hand

- Cold arm, hand or fingers (Mayo Clinic, 2016).

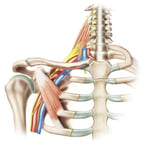

A common definition of TOS is compression of the brachial plexus

at the area of the first rib and clavicle - the thoracic outlet. Washington

University School of Medicine (n.d.) explains the thoracic outlet as the area

within the lower part of the neck, just above and behind the clavicle and

extending to the upper part of the arm (fig 1).

It is just lateral to the sternocleidomastoid and in front of the upper trapezius muscle and extends out behind the clavicle under the pectoralis minor and in front of the shoulder.

The brachial plexus exits the cervical spine, with nerve roots from C5 to C8 and T1,

and travels between the scalenes, over the first rib, under the clavicle, and behind the pectoralis minor to the shoulder and arm.

Therefore, an appropriate working definition of TOS is “a condition that involves the compression of the brachial plexus and its accompanying artery between the

anterior and middle scalene (anterior scalene syndrome), or the clavicle and

first rib (costoclavicular syndrome), or between the coracoid process and the

pectoralis minor (pectoralis minor syndrome)” (Ludwig, 2005, p. 825).

What are the Causes of TOS?

Due to the complexity of this trek, compression of the brachial plexus could occur at any of the locations mentioned above. Common causes of TOS are trauma, repetitive use injuries, anatomical anomalies, such as a “cervical” rib (longer than normal transverse process on the seventh cervical vertebrae – most accurately detected by X-ray), and poor posture.

Repetitive use, in this case, can be something as simple as carrying an extra-heavy purse or bag by a strap over the shoulder, or repetitive overhead movements, such as those experienced in overhead sports . The weight pulling down on the clavicle may compress the brachial plexus leading to TOS.

Repetitive use is closely associated with posture, as excessive downward rotation of the scapula can result in the same compression of the neurovascular bundle as it passes between the clavicle and first rib. Also, downwardly rotated and anteriorly tipped scapulae suggest overactivity of the pectoralis minor.

The tight pec minor may squeeze the brachial plexus (i.e., pec minor syndrome) causing TOS. Further, it is important to consider poor breathing patterns as non-optimal diaphragm function could cause overactive scalenes and pec minor (secondary respiratory muscles), which may again compress the vessels as they pass through the musculature.

Therefore, if a client has symptoms that align with TOS, it’s

important to identify the potential location of the compression.

Assessments for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

This is where the power of a specialization in Corrective Exercise really shines.

There are a variety of assessments that can be learned and performed safely, which narrow the space of a potential compression and increase the symptoms.

These assessments are not intended to diagnose or treat TOS, but they can help to direct attention and exercise programming. (Note: Clients should consult with their

physician if they have symptoms and/or have their physician perform these

tests.)

Also, it is recommended to review your state laws on whether or not you

may perform these tests. It is worth mentioning that results of any assessment

or test should be part of a comprehensive client assessment that includes

medical history, daily activity questionnaires, and other subjective and objective information.

As with many assessments, the failure to integrate data from a variety of sources may lead to false positives.

Overhead position (elevated stress test) - One of first, and easiest, tests to perform is a simple overhead position. Have the client reach both arms overhead, as though they were going to perform an overhead squat. While holding this position, have the client close and open their fist at a moderate pace for three minutes (Armstrong & Hubbard, 2016). These authors suggest that TOS may be present if there is an increase in symptoms on one side compared to the other.

Now we must try to identify the origin of the problem.

Each of the following tests are adapted versions of orthopedic exams. Each test description is so the client can perform the test on themselves, without the assistance of the fitness professional. Hold each position for 10-15 seconds. The positive result is if the client experiences an increase in the symptoms mentioned above.

Compression by an overactive anterior scalene (adapted from Adson’s test as described in Ludwig (2005)) – Have the client extend and slightly externally rotate the arm. Then rotate the head towards the affected arm, to slightly elevate the chin, and to take in a deep breath holding it for at least fifteen seconds. This position will elevate the first rib compressing the brachial plexus against a tight anterior scalene.

Compression by an overactive middle scalene (adapted from Travell’s variation on Adson’s test as described in Ludwig (2005)) – Have the client extend and slightly externally rotate the arm. Then rotate the head away from the affected arm and to take in a deep breath holding it for at least fifteen seconds. This position will elevate the first rib compressing the brachial plexus against a tight middle scalene.

Compression by an overactive pec minor (adapted from Wright’s hyperabduction test as described in Ludwig (2005)) – Have the client fully abduct the arm to 180 degrees and slightly flex the shoulder (i.e., hyperabduction; move the arm behind the ear assuming a neutral cervical spine). This position will place a stretch on the brachial plexus as it passes under the pec minor.

Compression at the first rib and clavicle (Ludwig’s (2005) alternative to the costoclavicular syndrome test) – Have the client perform scapula retraction and depression (i.e., Eden’s test).

If one or more of the above tests are positive, encourage clients to seek treatment from a qualified health professional (e.g., physical therapists, athletic trainer, medical doctor, etc.).

Once cleared for exercise, fitness professionals should implement a corrective exercise program aimed at correcting upper body dysfunction.

- Inhibit / SMR: Pec Minor, Upper Trapezius, Thoracic Spine

- Lengthen / Contract-Relax: Given the previous nerve issue, PNF or contract-relax stretching is recommended over static stretching

- Activation: Quadruped Protraction, Floor Combo

- Integration: Single-leg Scaption, Wide Grip Row

References