The overhead squat assessment is not limited to just lateral and frontal views. Taking a posterior view can add another dimension to identifying and addressing kinetic chain dysfunction. One of the more surprising observations is an asymmetrical weight shift at the lumbo-pelvic-hip checkpoint. Read on to see what it means and how to address it.

The overhead squat assessment is designed to assess dynamic flexibility, core strength, balance, and overall neuromuscular control (1). When taking a look at your client from behind during the assessment, the checkpoints to watch are the feet, the ankle complex and the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex (LPHC). Ideally, as they squat down you’ll observe only slight pronation of the foot and ankle complex, maintenance of the foot arch, and the heels will stay on the ground. Additionally the LPHC should not display any side-to-side shifting (1). But what does it mean if the LPHC shifts?

An asymmetrical shift at the LPHC checkpoint indicates the following muscles are probably overactive:

adductor complex and TFL on the same side of the shift, gastrocnemius/soleus, pifiromis, biceps femoris, and the gluteus medius on the opposite side of the shift

The probable underactive muscles include:

gluteus medius on the same side of the shift, anterior tibialis, and the adductor complex on the opposite side of the shift.

This movement compensation can lead to hamstring, quadriceps, and groin strains, along with low back and sacroiliac (SI) joint pain (1). Further compounding the challenge, individuals suffering from ankle sprains may also experience hip weakness even though the primary roles of the gluteus medius are as a hip abductor, rotator, and LPHC stabilizer (2-3). A weak gluteus medius has also been identified as a contributor to knee impairments (1-2).

How to Fix Hip Shift in The Squat

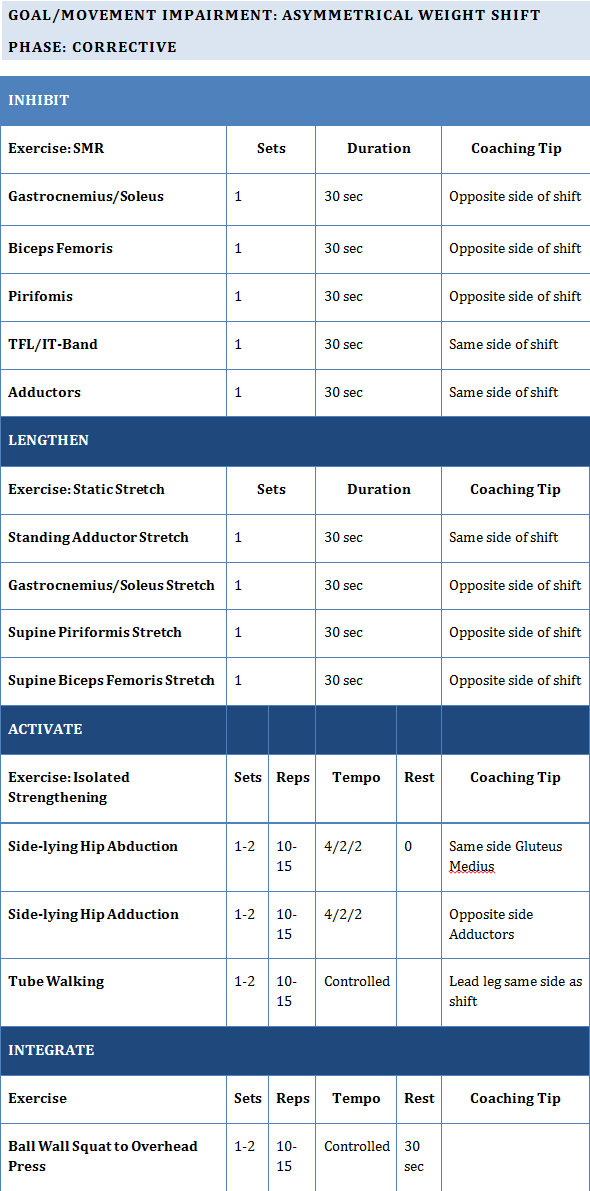

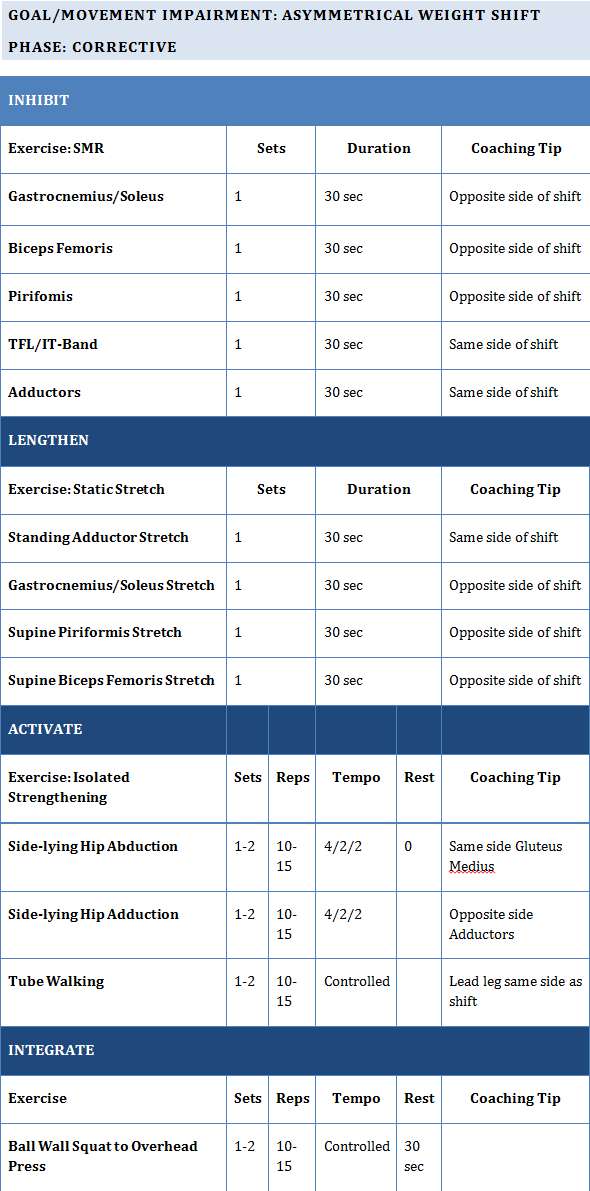

To address the asymmetrical shift compensation, following a corrective exercise program that includes inhibiting and lengthening the overactive muscles via self-myofascial release (SMR) and static stretching, followed by activating the underactive muscles with isolated strengthening exercises and dynamic movement integration. Here is a sample corrective exercise program for asymmetrical weight shift.

Help your client’s become “aware” of their underactive muscles. Include activities such as single-leg squats or lunges where they place their hands on top of their hips and watch in a mirror as they try to maintain the hands parallel to each other and avoid shifting. Use cueing such as keep the hips square or level so one hip does not drop. During an integrated activity, such as the ball wall squat, try applying gentle pressure to the outside of the thigh, pressing it toward the midline, so they’ll need to engage their gluteus medius to press their knees to the outside to overcome the pressure. Take advantage of their proprioceptive abilities and help them to focus on those muscles during the exercises. This corrected movement may initially feel wrong or awkward, but supporting their efforts with verbal, visual and proprioceptive information can help them gain, and maintain, a corrected movement pattern (3-4).

The overhead squat assessment can tell you a lot about your client’s potential movement impairments. This article only addressed the asymmetrical weight shift seen from a posterior view. To better evaluate your client, perform a complete assessment from all angles-anterior, lateral, and posterior- to address the entire kinetic chain.

References:

1. Clark MA, Lucett SL, NASM Essentials to Corrective Exercise Training. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011.

2. Neumann DA, Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, Foundations for Rehabilitation 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier. 2010.

3. Sahrmann SA, Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc. 2002.

4. Willy RW, Scholz JP, & Davis, IS. (2012). Mirror gait retraining for the treatment of patellofemoral pain in female runners. Clinical Biomechanics, 27(10):1045-51.