In a previous blog that compared static vs dynamic stretching, the NASM OPT model delineates what type of stretching is used at specific levels of training clients. This is especially important to know if you're a Stretching and Flexibility Coach.

- Corrective Flexibility for the stability level focuses on static stretching.

- Then Active Flexibility for the strength level focuses on active isolated stretching.

- Finally, the Functional Flexibility power training level progresses to dynamic stretches like prisoner squats, multiplanar lunges with reach, tube walking, medicine ball chop and lift, push-ups with rotation, and Russian twists.

What is Dynamic Stretching?

If one feels and then moves through any resistance that is felt beyond the normal ROM, then that experience qualifies as dynamic stretching. It is often easier to feel this resistance in one’s body when done at slower tempos, but it is felt more as a recoil, braking, or slowing down by the body or limb when done at faster tempos.

Updates to the NASM OPT™ Model Regarding Dynamic Stretching

Note: readers unfamiliar with the OPT Model and who wish to learn more, can enroll in NASM's Certified Personal Trainer program.

At the NASM 2020 Optima Conference, new guidelines and protocols for the OPT model were revealed which are discussed in detail in a previous blog . What is most relevant to this article was that dynamic stretching was added as an optional flexibility technique in all OPT model phases. This decision was based on new research that has emerged regarding warm-up and stretching protocols.

Based on the new guidelines, fitness professionals can now include dynamic stretching in all phases of the OPT Model (see figure 1). Much research demonstrates the benefits of dynamic stretching within a flexibility routine (Behm & Chaouachi, 2011; Behm et al., Blazevich, Kay & Mchugh, 2016; Kallerud & Gleeson, 2013; Opplert & Babault, 2018). Most if not all professional sports have incorporated different forms of dynamic stretching for many years and much fitness training and prehab/rehab programs have followed this protocol as well.

Dynamic stretching examples

As many readers may be familiar with the dynamic stretches previously mentioned in standing positions (prisoner squats, multi-planar lunges, tube walking, etc.), the next section will present more options that can be done on the ground or floor to help further customize the experience for the client.

Ground or floor dynamic stretches

This dynamic stretch program may be used pre- or post-activity, e.g., fitness training or sports (like dynamic warmup routines). The following stretches make up a dynamic progression from ground movements that can be added preparatory to more vigorous standing movements. It is best to do them after a light warm-up such as an easy jog or run for 5 to 10 minutes—just enough to generate very light perspiration. The stretches engage entire myofascial kinetic chains and may be named by kinetic chains or specific muscles that lie in targeted chains.

Core 4 focuses on dynamic flexibility preparation of the core muscles and the fascia of your lower body and progress to your upper body. The initial focus is dynamic core mobility, and the progression integrates motor control and dynamic core stability. This routine applies to most sports that require optimal core control (Frederick and Frederick 2017).

Program parameters

General Guidelines for Dynamic Mobility Preparation:

• Compare how you feel and move before and after these stretches. Over time, you will know which ones are the most beneficial.

• Make your movements flow.

• Exhale into the stretch, and inhale coming out of the stretch.

• Don’t count reps; rather, finish the movement when you are no longer making gains in flexibility.

• If the movement doesn’t loosen you up enough to perform, then do SMR (self-myofascial release) on the problem spot and try the stretches again.

• Never let your spine sag, but never hold your core so tight that you can’t move well during the stretches.

• These are dynamic stretch movements; you should not feel a big stretch. Use less intensity and faster tempos and do as many reps as are needed to feel more mobile but still strong and ready to perform.

For cooldowns, perform the same movements but about 3x slower by taking slower and longer breaths. Make the stretch movements last longer so that you are still moving and not holding the stretch (unless you are doing a static stretch for different reasons and purposes). Explore different angles in each movement to customize your needs at that moment.

Hip-Spine-Shoulder Stretch

This movement warms up the hip joint capsule fluids and focuses on the rotational components of the lumbo-pelvic-hip region. Do this before all other hip movements on the ground.

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. Sit on the ground with the knees bent and the feet slightly wider than hip-width apart. Place the arms behind you with the palms on the floor and the fingers pointing away from the body (see figure 2).

2. Exhale, lean the torso back, and slowly drop both knees to one side (see figure 3).

3. Inhale and return to center.

4. Exhale and repeat, dropping both knees to the other side.

5. Continue dropping the knees from side to side.

Figure 2

Figure 3

ADD UPPER BACK AND SHOULDER

1. Lie on your back with the arms out and repeat the hip and leg movements. Note how your ROM has decreased. Try to push your knees down to the floor with your hips without strain or pain (see figure 4). Repeat until no further gains are noted.

2. Next, drop the legs to one side, and keep them there. Move the arm opposite the direction of the legs up and the other arm down by sweeping them on the ground (see figure 5), and/or try with other arm motions at different angles. Try to follow your hand with your eyes and head. Repeat on the other side.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Core 4 on the Floor™

The Core 4 of the lower body is made up of the power-generating regions for most movement in fitness and sports (see figure 6.2). In terms of bones and joints, this would be your lower lumbar-pelvic-hip area. In terms of muscles, this would be all your core muscles and fascia (lumbodorsal or thoracolumbar fascia, transversus abdominis, obliques, deep and superficial back extensors, iliopsoas, glutes, and deep hip rotators).

These muscles and associated fasciae, especially those surrounding the hips, provide the foundation for many athletic movements that many athletes depend on for performance. Therefore, it is extremely important to achieve balance in mobility in your lower-body Core 4 to generate the energy-efficient, powerful functioning that is required in most sports and in high-level fitness training.

The following anatomy of the Core 4 will describe each region by first naming the key muscle and its associated region of muscles and fascia that are positioned in the same kinetic chain (Frederick and Frederick 2017, 2020). Therefore, when performing Core 4 consider that you are not only warming up the key muscle but also the entire associated kinetic chain of myofascial.

Dynamic stretching to improve mobility in the lower body first makes sense because it is the base or foundation for most sport and athletic movements. Four key lower-body muscles and their kinetic chains are identified that you should work to improve mobility:

• Glute, hip and back warm-up (includes myofasciae below in the proximal hamstring and above in the lower to upper back and neck).

• Rotation warm-up for hip, back, neck (includes quadratus lumborum bilaterally and myofasciae around the entire waist and hips below and into the torso rotators and neck above).

• Hip flexor warm-up (includes iliopsoas and the myofasciae below in the thigh and groin and above along the entire front of the abdominals and neck).

• Lat to low back warm-up (includes latissimus dorsi and myofasciae from the low back and pelvis on up to the shoulder and chest).

Note that the latissimus dorsi is included in this group because it attaches to both the lower back and the pelvis, as well as the shoulder. It functions as a bridge that connects the lower body to the upper body.

The lower-body Core 4 program opens areas that may be causing restriction around your hips and low back, which will also help regions higher up (e.g., the spine and shoulders) and lower down (e.g., the knees, ankles, and feet) because of the long, extensive connections through your fascial net. Complete the entire Core 4 on one side of your body before stretching the other side.

1. GLUTE, HIP AND BACK WARM-UP

INSTRUCTIONS:

1) Sit on the floor and place one leg in front and one behind, and bring the front foot inward until the foot touches the back knee, or as close as possible (figure 6a). Position your weight so you are sitting more on the glute of the front leg. Make adjustments for comfort. Place your hands in a push-up position in front of you with the arms straight.

2) As you inhale, lengthen the whole spine up through the top of your head; then, exhale and move down and forward over the knee, keeping spine long (figure 6b).

3) Roll up through the spine back to the erect starting position.

4) Repeat, taking the torso forward to the left and right of the knee at different angles to target the different glute fibers.

TIPS

• Breathe and wave into and out of the stretch until you feel your tissues release.

• Drop your body closer to the floor and move from side to side.

• Complete the rest of the following stretches before doing the other side.

Figure 6a

Figure 6b

2. ROTATION WARM-UP FOR HIP, BACK, NECK

INSTRUCTIONS:

1) From the glute stretch position, walk the hands back until you feel a slight stretch in the back, hips, and/or legs (figure 7a).

2) Keep the hands still and lean toward the hand that is on the same side as the front leg, and inhale (figure 7b).

3) Exhale as you lean back again.

4) Repeat.

TIPS

• Walk the hands out a little farther with each repetition to progress the stretch.

• Complete the rest of the following stretches before doing the other side.

Figure 7a

Figure 7b

3. HIP FLEXOR WARM-UP

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. From last position in the previous stretch, place the back forearm on the ground and find a stable position where you can balance on that arm with full weight. Slide the forearm to the rear as your back starts to arch and stop when you feel a mild stretch. Inhale and lean forward on both hands (figure 8a).

2. Exhale while you arch the back and look up to ceiling (figure 8b) feeling the stretch in your hip flexors (and sometimes the back).

3. Repeat.

TIPS

• Lean back farther to progress the stretch.

• Find the stretch by arching the back rather than twisting it.

• Complete the last stretch below before doing the other side.

Figure 8a

Figure 8b

4. LAT TO LOW BACK WARM-UP

INSTRUCTIONS:

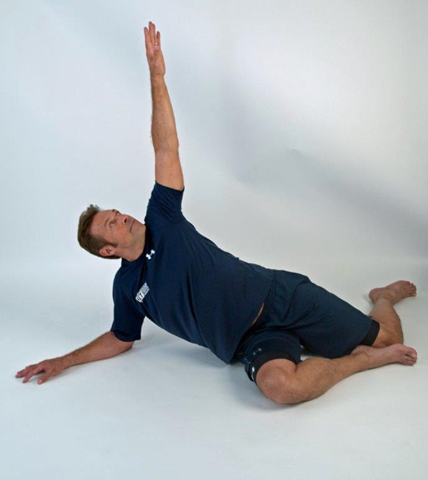

1) From the last position in the previous hip flexor stretch, inhale and reach your arm overhead (figure 9a).

2) Extend the arm out from the hip as you reach. This looks like you are swimming in the air (figure 9b).

3) Exhale as you rotate the chest toward the floor while you reach the arm out.

4) Circle your arm down and back up overhead.

5) Repeat.

TIPS

• Keep reaching the arm throughout stretch for maximal effect.

• Try to get the chest more parallel to floor with each rep.

REPEAT ENTIRE SERIES FROM BEGINNING ON OTHER SIDE

Figure 9a

Figure 9b

Summary

Adding and ending with ballistic movements for an even more complete warm-up (e.g., partial squat progressed to full squat progressed to burpees) would be appropriate if preparing for performing power movements in training or sports (Frederick and Frederick 2017).

Any full body (or isolated torso and/or limb) movement performed through a partial or full ROM without encountering tissue or joint resistance would qualify as a ROM exercise. There is no use of equipment of any kind and movement may be done in many varied positions of standing, sitting, or on the ground.

A complete warm-up before activities like fitness training and sports progress from a 5–10-minute activity like a light jog or stationary bike or full body ROM before progressing to dynamic stretches. Dynamic stretches can be done on the ground and progress to standing with increased tempos and frequencies (repetitions) until one feels sufficiently warmed-up to engage in the intended activity. The person should feel alert, mobile, and ready for high intensity activity.

Dynamic stretches can also be used to cool down after activity to support a complete and efficient recovery. Tempos are slow so that breathing, and duration of stretches are longer to oxygenate and rehydrate tissues, flush metabolic waste, and restore flexibility. The person is encouraged to keep moving in the stretches to explore various angles to individualize the stretch for their specific needs. This protocol will both increase and maintain flexibility and mobility for an active lifestyle.

If you want more examples of great stretches to improve your flexibility, read Stretching for Beginners.

References

Behm, D. G., & Chaouachi, A. (2011). A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 111(11), 2633–2651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-1879-2.

Behm, D. G., Blazevich, A. J., Kay, A. D., & McHugh, M. (2016). Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: A systematic review. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0235.

https://blog.nasm.org/fitness/is-static-stretching-the-best-strategy-for-injury-prevention-and-performance-enhancement

https://blog.nasm.org/new-opt-model-updateshttps://blog.nasm.org/new-opt-model-updates

Frederick, A., Frederick, C. (2017). Stretch to Win. 2nd ed. Human Kinetics.

Frederick, A., Frederick, C. (2020). Fascial Stretch Therapy™. Handspring Publishing Ltd.

Kallerud, H., & Gleeson, N. (2013). Effects of stretching on performances involving stretch-shortening cycles. Sports Medicine, 43(8), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0053-x.

Opplert, J., & Babault, N. (2018). Acute effects of dynamic stretching on muscle flexibility and performance: An analysis of the current literature. Sports Medicine, 48(2), 299–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0797-9.