Stephanie is your newest fitness client. She’s 42 years old and works 50 hours a week as a certified public accountant. She would like to quit smoking, give up junk food and get active—all the foundations of a healthy lifestyle.

Fast-forward 6 months. Stephanie is still smoking and still lunching on cheeseburgers. She keeps skipping workouts. Why can’t she exercise regularly or stick to a healthy eating plan? Stephanie may not even know why herself. If that’s the case, then how can you help her behave differently? There’s no shortage of health education campaigns encouraging her to change her ways. The challenge is to help her use that education to make lasting behavior changes.

Influencing Stephanie’s health behavior is much more critical than creating exercise routines, reviewing food choices, monitoring progress and being supportive. To succeed in helping Stephanie adopt and maintain a healthier lifestyle, you need to understand the mechanisms—the how and why—and the theories behind behavior change science.

To earn 2 AFAA/0.2 NASM CEUs, purchase the Behavior Change Science CEU Corner quiz ($35) and successfully complete it online at www.afaa.com.

The Roots of Behavior Change

Where do you start? Research encourages adopting a theoretical base for behavior change interventions because that will work better than a random, theory-free approach (St. Quinton 2017). When you incorporate the elements of a well-studied theory, you can identify the key factors and processes that affect people’s ability to adopt physical activity and wellness strategies (Hagger & Chatzisarantis 2014).

A lot of research has delved deeply into behavior change to show why different interventions work for one person but not another. Selecting the right theoretical base can be a crucial step in developing successful fitness and lifestyle programming. But this is a daunting task, owing to the sheer number of theories. This article will help you navigate some of the research on behavior change science and show you ways to apply some of the most important theories.

Four Proven Paths to Behavior Change

At least 83 formal theories of behavior change have been developed, and more emerge all the time (Teixeira & Marques 2017). That seems like a sky-high number, but you don’t need to know them all. The most thoroughly tested strategies are the Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory, the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Transtheoretical Model.

HEALTH BELIEF MODEL

The Health Belief Model focuses on how Stephanie’s attitudes and beliefs explain and predict her behaviors. The theory behind the HBM is that Stephanie’s desire to prevent illness and her belief that a specific action can achieve that goal will motivate her to implement healthy behavior changes. One challenge with the HBM is that people who do not feel susceptible to a disease/condition are less likely to want to change their behaviors.

The HBM has been applied in the development of behavior change for 40 years, amassing a large body of empirical evidence of its success. A literature review found that 78% of studies exploring the HBM reported significant improvements in adherence (Jones, Smith & Llewellyn 2014).

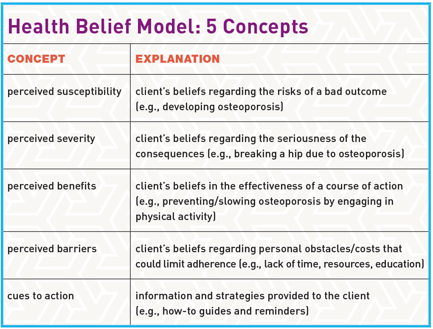

The HBM has five core concepts: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers and cues to action (see “Health Belief Model: 5 Concepts,” above). The strongest predictors of behavior are perceived benefits and perceived barriers (Jones, Smith & Llewellyn 2014). One of the biggest drawbacks of the HBM is that it does not weigh the economic, environmental or socio-structural factors affecting change.

SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY

Social Cognitive Theory is based on the belief that behavior results from continuous interactions among environment, individual and behavior. It’s built on the idea that when Stephanie understands health risks and benefits, the precondition for change exists within her. If she doesn’t know how her lifestyle habits affect her health, then she doesn’t have much reason to endure the challenges of giving up her favorite bad habits (Bandura 2004).

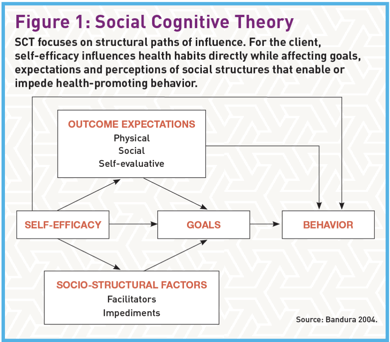

SCT proposes that behavior is a deliberate and conscious process for seeking positive outcomes and avoiding negative ones. It notes that while environment can alter people’s behavior, people can alter their environments to achieve desired outcomes (Lee et al. 2018). SCT identifies four determinants of behavior: self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals and socio-structural factors (see Figure 1).

THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR

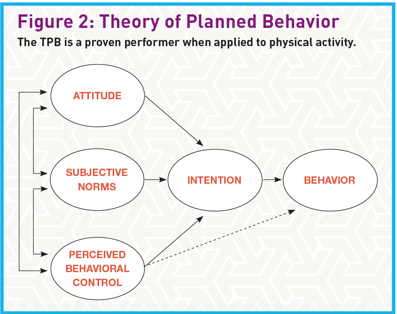

The Theory of Planned Behavior is one of the most widely used and well-researched theories applied to exercise. Several literature reviews show its efficacy in predicting and explaining physical activity. The TPB combines clients’ expectations about performing a behavior with the value that clients attach to that behavior (Tenenbaum & Eklund 2014) (see Figure 2).

The TPB defines four main psychological factors affecting behavior change: attitude (positive or negative evaluation of performing a behavior), intention (willingness), subjective norms (perceived social pressure) and perceived behavioral control. Two of the strongest behavior predictors are intention and perceived behavioral control (perceived ease or difficulty).

One of the biggest drawbacks of the TPB is the consistently imperfect link between intentions and actual behavior change. As Stephanie’s example shows, many people have good intentions but fail to carry them out (Hagger & Chatzisarantis 2014).

TRANSTHEORETICAL MODEL

The Transtheoretical Model is based on empirical evidence suggesting that people go through five stages of readiness to change. To help Stephanie work toward success, you will need to understand when and how she is likely to change her behavior. That will mean tailoring exercise programs to the stage she’s in now.

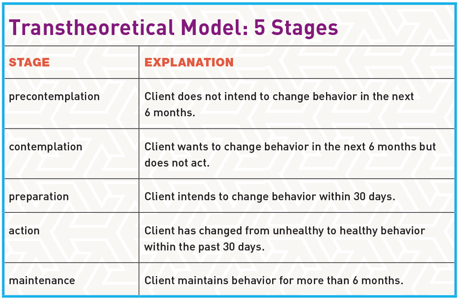

How do you identify that stage? The TTM recognizes five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance (see “Transtheoretical Model: 5 Stages”).

Progression through these stages is cyclical, not linear. Stephanie may move back and forth depending on the stimuli and barriers she faces. Indeed, relapse is an important part of the process. You can use relapses to teach Stephanie how to stay in the maintenance phase (Hall, Gibbie & Lubman 2012). For example, you can explain that cyclical behavior is normal and expected and that she can always pick up where she left off. This dynamic, rather than all-or-nothing, view of behavior change is one of the biggest strengths of the TTM (Marshall & Biddle 2001).

Choosing the Right Strategy

Each theory has strengths and drawbacks because of its particular focus on constructs, stages and phases. Thus, you have to decide which focus is appropriate for each client’s specific goals, the nutrition habits they want to change, and more.

For example, the Health Belief Model does not account for environmental and social-cultural factors, while Social Cognitive Theory relies heavily on continuous interactions between people and their environments. Thus, if a client’s lack of physical activity is heavily influenced by his or her peers, work or family, SCT might be the better approach.

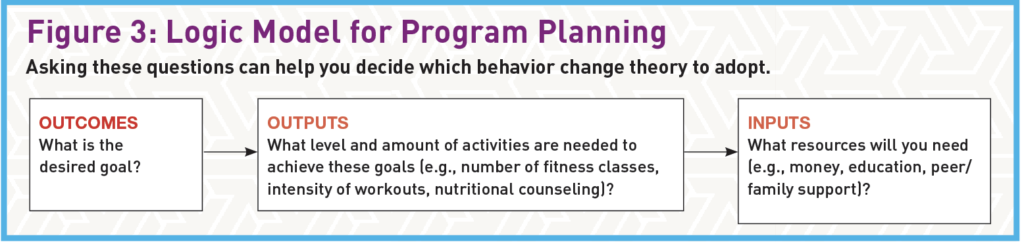

Choose an approach based on the client’s desired outcomes and circumstances. Start by identifying the problem, goal and units of practice. Don’t select a theory only because it’s intriguing, familiar or popular. One strategic way to select the right theory is to use “a logic model of the problem and work backward to identify potential solutions” (Green & Kreuter 2005) (see Figure 3).

Behavior Change Coaching and Scope of Practice

It’s important for fitness professionals to stay within their scope of practice. Coaching involves a set of skills related to, but different from, those used in counseling, therapy and consulting. Fitness pros do not analyze a client’s childhood, for example, but rather focus on the present. How might the client’s current situation be improved? What are some possible solutions? The main goal is for the client to “graduate” and continue on the path established through the partnership.

Behavior Change Techniques

While behavior change models form the conceptual foundation for exercise programs, behavior change techniques are the “active ingredients” (Teixeira & Marques 2017). They represent the “smallest identifiable components that in themselves have the potential to change behavior” (Michie et al. 2018).

The major behavior change techniques are contingency contracting, premacking, stimulus control, modeling and relaxation training (Kirschenbaum 2014).

CONTINGENCY CONTRACTING

This technique includes “explicit agreements specifying expectations, plans and/or contingencies for the behavior(s) to be changed” (Kirschenbaum 2014).

Contingency contracting has four stages: Establish specific and clear target behaviors (such as dietary activities and workout quantity and length), monitor progress, deliver consequences, and maximize generalization (establish reinforcing factors such as joining a healthy-eating group or getting an exercise partner).

PREMACKING

This involves reinforcing a desired behavior by pairing it with a likely behavior. For example, Stephanie could organize a football-watching party at home, where she could serve healthy snacks, rather than go to a sports bar that’s serving fried appetizers and beer.

STIMULUS CONTROL

Evidence shows that impulsive automatic factors drive many behaviors (Hagger & Chatzisarantis 2014), and controlling stimuli aims to reduce impulsiveness. For instance, Stephanie could take healthy food to work so it would be easier to avoid the temptation of going out for cheeseburgers at lunch or grabbing free doughnuts in the break room.

MODELING

With modeling, Stephanie would learn by seeing somebody else doing things she wants to do. Two types of modeling help people change: behavioral coaching (e.g., explaining and demonstrating proper execution of an exercise, having clients imitate it, and correcting their form) and assertiveness training (e.g., learning to fend off peer pressure to eat foods that don’t fit the desired plan).

RELAXATION TRAINING

This training teaches clients proven methods to help them find a state of relaxation. Examples include progressive muscle relaxation, cued relaxation and deep breathing.

Helping Clients Surmount Behavioral Obstacles

Knowing the barriers to physical activity, healthy eating and other healthy behaviors is crucial to helping clients change their behavior for the long haul. There are four primary categories of barriers:

- environmental—climate, space, equipment

- social—work, family commitments, lack of social support

- behavioral—concerns about appearance, lack of interest

- physical—chronic fatigue, generalized pain, body limitations

(Boscatto, Duarte & Gomes 2011)

Keep in mind that clients often confront multiple barriers. For instance, most life-threatening conditions in the U.S. are influenced by several risk factors, including use of tobacco and alcohol, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition. Researchers found that 92% of people who smoked had at least one additional risky behavior, and 9 out of 10 overweight women had at least two eating or activity risk behaviors (Prochaska, Spring & Nigg 2008).

Given Stephanie’s habits, you know she needs help dealing with multiple behaviors. That means “bundling” services such as workouts and basic nutrition guidance into one program. That way, she can achieve more of her immediate goals (weight loss, strength development, etc.) while you promote the maintenance of these behaviors well into the future.

Summary: Putting Theory Into Practice

How often have we seen clients abandon their workouts after reaching their weight loss goals? That’s the behavior we want to turn around. Employing sound behavior change theories is central to making that happen.

All of the behavior change science models discussed in this article have been successfully applied to physical activity and healthy eating. Thus, you can apply any of them with your clients.

Avoid the urge to depend on personal preference and familiarity when choosing a behavior change theory. Using a logic model (see Figure 3) can help you choose wisely.

Behavior change techniques require careful selection to match clients’ goals. One client might benefit from contingency contracting, while another might not respond well to having a “contract” but could respond well to relaxation training. As clients confront the stages and barriers of behavior change, you’ll have to continually adjust your techniques.

So, yes, you can help Stephanie succeed. Now that you have a greater understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of behavior change science, you will be better able to help all of your clients effectively switch to new, healthy behaviors and maintain them for months and years to come.

To earn 2 AFAA/0.2 NASM CEUs, purchase the corresponding online CEU quiz for $35 and successfully complete it.

The Basics of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is a type of talk therapy based on the idea that our thoughts play a central role in our beliefs, feelings and behaviors. This type of therapy aims to improve people’s ability to respond to challenging, stressful situations and to change the way they think, feel and act. CBT makes people aware of inaccurate or negative thinking, giving them a clear view of challenging situations, which helps them respond more effectively (Mayo Clinic 2018).

CBT includes many types of treatments, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and metacognitive therapy (McMain et al. 2015). It has typically been applied in the treatment of mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and eating disorders. It has also been used to manage stress and pain (McMain et al. 2015).

Remember that therapy is the work of people with specific clinical training, licensing and professional experience. Thus, it’s outside the scope of a fitness professional’s work. While you cannot conduct CBT with clients, you can encourage them to explore guided self-help based on the principles of CBT.

THE MULTIMODAL APPROACH

Some people are better off using more than one mode of behavior change (Teixeira & Marques 2017). That’s the principle espoused in the multimodal approach, which has been applied to many areas, including health and life coaching. Psychologist Arnold Lazarus pioneered this approach in the 1970s. Grounded in social and cognitive theories, his theory holds that no single system provides a full understanding of human development or behavior.

The multimodal approach focuses on seven interactive dimensions, represented by the acronym BASIC I.D.: behavior, affect, sensations, images, cognitions, interpersonal relationships, and drugs/biology. Several factors need to be considered when using this method: “What intervention, by whom, is most effective for this individual with that specific problem and under which set of circumstances?” (Palmer 2012).

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

Motivational interviewing is a collaborative counseling method that has succeeded in obesity and diabetes interventions. Efficacy studies have shown that people attending MI-based sessions in addition to complying with their regular interventions improved their adherence to physical activity (Christie & Channon 2014; Armstrong et al. 2013).

With MI, the coach is a facilitator rather than an authoritative expert. The focus is on evoking and honoring the client’s autonomy (Hall, Gibbie & Lubman 2012). It is important to accept that the client is responsible for his or her own changes and cannot be forced.

MI has four principles under the acronym RULE: Resist the righting reflex (wanting to “make things right” when we see a problem), understand the client’s motivations, listen with empathy, and empower the client.

Thus, the coach focuses on what clients can do rather than telling them to do something. Helping clients connect what they care about with the motivation for change can be helpful. For example, an older client may want to be able to play with his or her grandchildren and see them grow up.

Basic MI skills include asking open-ended questions, making affirmations, using reflections and summarizing.

A Quick Look at Motivational Interviewing

This technique identifies how important the change is and the discrepancy between clients’ current situation and where they want to be. Highlighting this discrepancy is at the core of motivating people to change.

STEP 1: USE “CHANGE TALK”

Sample questions: On a scale from zero to 10, how important is it for you to lose weight? Where would you be on this scale? Why are you at ____ and not zero? What would it take for you to go from ____ to (a higher number)?

STEP 2: BUILD CONFIDENCE IN THE ABILITY TO CHANGE

Sample questions: On a scale from zero to 10, how confident are you that you can increase the number of days you exercise? Where would you be on this scale? Why are you at ____ and not 10? What would it take for you to go from ___ to (a higher number)?

STEP 3: CHOOSE A CHANGE PLAN TOGETHER

Sample summary statement: It sounds like you don’t want things to stay the same. We need to answer these questions:

- What do you think you might do?

- What changes were you thinking about making?

- Where do we go from here?

- What do you want to do at this point?

Source: Hall, Gibbie & Lubman 2012.

Technologies to Help Behavior Change

Technology can play a vital role in behavior change success. Posts on social media sites and mobile apps can also be crucial accountability tools that help clients stay on track and avoid the temptation to stray.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Research shows that social networking sites such as Facebook, Instagram and health-specific platforms can help people change their behaviors. Moreover, studies researching social networking and cognitive theory have shown that those who use a social media site to support health-related changes, such as weight loss and increased physical activity, had a higher probability of successful behavioral change (Laranjo et al. 2015).

For fitness professionals, there are several advantages to social media sites, including their low cost and the ability to customize programs to individual clients. We also know that delivering behavior change techniques over a variety of modes increases their effect on health-related behaviors (Teixeira & Marques 2017). What’s more, social media sites use clients’ existing social networks, further encouraging your clients to integrate behavior change into their daily lives (Laranjo et al. 2015).

MOBILE WELLNESS APPS

The most common barriers to physical activity and healthy eating are lack of time and lack of knowledge. Many clients feel overwhelmed by the prospect of preparing healthy food, reading nutrition labels, tracking workouts and counting calories. Fortunately, mobile apps have sprung up to help clients adapt.

Apps can educate clients about diets and help clients identify healthy choices when dining out. Apps can also track food intake and exercise output and find locations for seasonal produce (Lowe, Fraser & Souza-Monteiro 2015).

Knowing about these apps—and how to use them—can help you show clients how to overcome their barriers to change. Another strength of apps is their ability to keep you connected with clients, send them cues to action and help them find communities that provide additional support. Recent research shows that increasing numbers of people are using online virtual health communities because they provide crucial emotional support (Lowe, Fraser & Souza-Monteiro 2015).

See these fitness motivation tips for more great ideas!

Risks of Resisting Change

People who can’t change their health behaviors face a raft of well-known risks:

- Every year, poor diet and lack of exercise are linked to 300,000 U.S. deaths (CDC 2017).

- About 42% of cancer cases are linked to modifiable health behaviors (ACS 2017).

- Smoking is linked to 1,300 deaths every day (CDC 2018), while obesity affects 39.8% of adults and 18.5% of children in the United States (Hales et al. 2017).

References

ACS (American Cancer Society). 2017. More than 4 in 10 cancers and cancer deaths linked to modifiable risk factors. Accessed Oct. 3, 2018: cancer.org/latest-news/more-than-4-in- 10-cancers-and-cancer-deaths-linked-to-modifiable-risk-factors.html.

Armstrong, M.J., et al. 2013. Motivational interviewing-based exercise counselling promotes maintenance of physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 37 (4, Suppl.), S3.

Bandura, A. 2004. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31 (2), 143–64.

Boscatto, E.C., Duarte, M.F.S., & Gomes, M.A. 2011. Stages of behavior change and physical activity barriers in morbid obese subjects. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano, 13 (5), 329–34.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. Physical inactivity: What’s the problem? Accessed Oct. 3, 2018: cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/entertainment ed/tips/PhysicalInactivity.html.

CDC. 2018. Fast facts: Diseases and death. Accessed Oct. 3, 2018: cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm.

Christie, D., & Channon, S. 2014. The potential for motivational interviewing to improve outcomes in the management of diabetes and obesity in paediatric and adult populations: A clinical review. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism, 16 (5), 381–87.

Glanz, K., & Bishop, D.B. 2010. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health, 31 (1), 399–418.

Green, L.W., & Kreuter, M.W. 2005. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hagger, M.S., & Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. 2014. An integrated behavior change model for physical activity. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 42 (2), 62–69.

Hales, C.M., et al. 2017. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief No. 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Hall, K., Gibbie, T., & Lubman, D.I. 2012. Motivational interviewing techniques: Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Australian Family Physician, 41 (9), 660–67.

Jones, C.J., Smith, H., & Llewellyn, C. 2014. Evaluating the effectiveness of health belief model interventions in improving adherence: A systematic review. Health Psychology Review, 8 (3), 253–69.

Kirschenbaum, D. 2014. NASM Behavior Change Specialist Course.

Laranjo, L., et al. 2015. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22 (1), 243–56.

Lee, C.G., et al. 2018. Social cognitive theory and physical activity among Korean male high-school students. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12 (4), 973–80.

Lowe, B., Fraser, I., & Souza-Monteiro, D.M. 2015. A change for the better? Digital health technologies and changing food consumption behaviors. Psychology & Marketing, 32 (5), 585–600.

Marshall, S.J., & Biddle, S.J.H. 2001. The transtheoretical model of behavior change: A meta-analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 23 (4), 229–46.

Mayo Clinic. 2018. Cognitive behavioral therapy. Accessed Oct. 3, 2018: mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/about/pac-20384610.

McMain, S., et al. 2015. Cognitive behavioral therapy: Current status and future research directions. Psychotherapy Research, 25 (3), 321–29.

Michie, S., et al. 2018. Evaluating the effectiveness of behavior change techniques in health-related behavior: A scoping review of methods used. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 8 (2), 212–24.

Palmer, S. 2012. Multimodal coaching and its application to workplace, life and health coaching. Coaching Psykologi, 2 (1), 91–98.

Prochaska, J.J., Spring, B., & Nigg, C.R. 2008. Multiple health behavior change research: An introduction and overview. Preventive Medicine, 46 (3), 181–88.

St. Quinton, T. 2017. The ‘scientific’ approach for the physical activity behavior change. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 17 (2), 722–29.

Teixeira, P.J., & Marques, M.M. 2017. Health behavior change for obesity management. Obesity Facts, 10 (6), 666–73.

Tenenbaum, G., & Eklund, R.C. 2014. Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.