Originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of American Fitness Magazine.

It’s likely that many of your clients spend the majority of their time

sitting at a desk, staring at a screen. They then sit in their cars for a long

commute. When they arrive at their final destination, they sit down to eat and then watch television. If they make it to the gym, they often sit on a recumbent bike or use selectorized strength equipment. That’s a lot of sitting.Your challenge is to help them combat the deleterious effects of such limited

movement and encourage them to meet and surpass their health, fitness and

wellness goals.

Ideally, our cultural norms wouldn’t include so much time spent seated,

but the reality is that many fitness pros work with clients who must

sit to earn a livelihood—and they likely sit more during the rest of the day.

Seated time is linked with higher death risks from all causes (Ku et al. 2018).

The issue, however, is nuanced. Research reveals that simply standing more is not the answer. And even people who work out a few hours per week are not protected from the negative consequences of excessive sitting (Akins et al. 2019).

How can fitness professionals help deskbound clients? First, it’s important to understand what the health risks of sitting are and how best to combat them. Second, there are a number of workplace options for reducing sitting—what are the pros and cons of treadmill, cycling or sit-to-stand desks? Third, fitness pros can offer evidence-based tips and training program options to alleviate the strains of a seated lifestyle.

The Hazards of Desk Work

Prolonged sitting is linked to an increased risk, in general, of any cause of death. Recent studies investigating an association between sitting time and increased death risks are looking more closely at whether data is self-reported (typically inaccurate) versus measured by devices, and whether differences exist among adults ages 64 and younger versus adults over age 64. This article focuses on adults ages 64 and younger and cites studies with accelerometer-measured data, except where noted.

Researchers are refining our understanding of how many hours of sitting per day increase risks and the types of breaks that provide the most protection from harm. According to a review study with over 1 million participants, adults ages 18–64 should sit less than 7.5 hours to avoid increased risk of death from all causes (Ku et al. 2018). Additional sitting time over 7.5 hours has a linear relationship with increased death risks.

Sitting for long hours is related to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic diseases, cancer and musculoskeletal issues. Scientists think a sedentary lifestyle exacerbates some of the following conditions:

Low physical fitness level.

Lack of movement results in deconditioning. Cardiorespiratory fitness decreases, and muscular strength, endurance and flexibility decline.

Poor pulmonary function.

Slouching restricts the diaphragm’s movement, limits lung volume and weakens respiratory muscles.

Poor circulation and vascular health.

Lack of activity brings about compromised circulation, less vascularization, less blood vessel elasticity, blood pooling, increased risk of blood clots and more inflammatory factors.

Muscle and joint stiffness.

Stiffness develops because muscle fibers shorten due to inactivity and because there is less hyaluronic acid for joint lubrication.

Higher osteoporosis risk.

Reduced movement, lower levels of growth hormone and lack of growth factors necessary for muscle and bone development can all be an issue.

Increased insulin resistance.

This occurs when regulation of enzymes affecting glucose uptake is compromised; poor regulation contributes to elevated insulin levels and impaired lipid metabolism.

Weight gain.

Inactivity leads not only to fat gain but also to metabolic changes that reduce exercise capacity, impede glucose uptake, and impair muscle development and fat metabolism. Preliminary research shows that these metabolic changes also occur in individuals who exercise regularly.

Sleep quality.

Poor melatonin production interferes with a good night’s rest. This promotes daytime fatigue, possibly increasing the sympathetic response, elevating heart rate and raising blood pressure (Lurati 2017; Akins 2019).

It’s clear that no one factor is responsible for the increased health

risks of prolonged sitting; inactivity affects all aspects of physiological

functioning.

Break Up Sitting Time

Since sitting is essential in modern life, how can we reduce the resulting health risks? The latest research suggests that the best approach is to break up seated time with short movement sessions of any intensity—what is important is to move, even if only for 1 minute at a time. Researchers at Columbia University in New York tackled this quandary by examining whether it’s necessary to exercise, to simply move or to sit for shorter lengths of time. Investigators analyzed data on activity levels and death rates from approximately 8,000 adults, ages 45 and older, over 4 years. The researchers learned that 30 minutes per day of physical activity of any intensity—even in bouts of 1–2 minutes at a time—reduced risks of early death (Diaz et al. 2019).

Another study from Columbia University suggests that, ideally, sitting bouts should not last more than 29 minutes without a movement break. Over about 4 years, researchers evaluated data from almost 8,000 black and white volunteers, ages 45 and older, who wore hip accelerometers. Subjects included men and women. Those who interrupted their sitting at least every 30 minutes had the lowest death risks. Study authors advised that both reducing and regularly breaking up sedentary time may be important adjuncts to existing physical activity guidelines (Diaz et al. 2017).

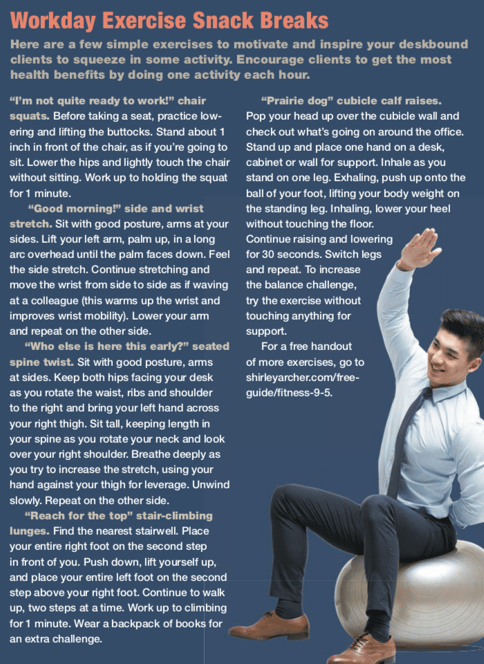

Try “Exercise Snacks”

Another way to support deskbound clients is to suggest they take regular exercise snack breaks. Studies show that multiple short movement bouts provide a training effect. The term “exercise snacks” was coined in 2014 by New Zealand researchers looking for a way to improve glucose control among individuals with insulin resistance (Francois 2014). In a recent study of 24 healthy, sedentary male and female young adults, Canadian investigators found that a few minutes of vigorous stair-climbing 3 times per day, 3 days per week, for 6 weeks improved cardiorespiratory fitness. The exercise snacks included warming up with 10 jumping jacks, 10 squats and 5 lunges on each leg, followed by quickly ascending three flights of stairs (a 60-step staircase) and then cooling down for 1 minute with level walking. All participants were formerly inactive, and all improved their cardiovascular fitness (Jenkins et al. 2019). This is good news for clients who are frustrated that they don’t have time for long workouts every day.

What About Active Workstations?

Should you tell clients to simply stand more often? Standing may address

some musculoskeletal and postural issues influenced by prolonged sitting, but it

creates other challenges. For example, studies show that long-term standing can

increase risks of varicose veins and heart disease, particularly for men with

ischemic heart disease, since standing puts more strain on the circulatory

system and on the legs and feet (Krause et al. 2000). Other studies show

increased discomfort from prolonged standing. And a 6-year study of 293

Canadian adults ages 18–65 found that people who reported engaging in more

worktime standing did not experience less incidence of overweight, obesity,

glucose intolerance or type 2 diabetes than those who sat (Chaput et al. 2015).

It seems, therefore, that the key problem is not sitting per se, but rather lack of

physical movement.

Active workstations can address this to a certain degree. A recent

research review sheds light on the pros and cons of three options:

sit-to-stand, treadmill and cycling workstations. Université de Montreal,

Quebec, researchers reviewed 12 studies. All active workstations improved

short-term productivity, a particular concern for employers. Treadmill

workstations affected keyboarding motor skills the most. Cycling and treadmill

stations improved heart rate and energy expenditure, increased alertness and

reduced boredom more than standing stations did; but cycling stations enabled

workers to process simple tasks most quickly (Dupont et al. 2019). On the

positive side, no acute or chronic injuries were associated (during the study)

with these workstation alternatives (Tudor-Locke et al. 2014).

Marie-Eve Mathieu, PhD, an author of the study done by Dupont et al.,

advocates for more research. “Ultimately, workers and corporations should be

able to critically examine the benefits and limitations of each type of

workstation and determine which is most appropriate for [a] worker’s specific

needs and tasks.”

Best Practice to Date: Movement Breaks and Training

Based on what we know from studies to date, fitness pros can help deskbound clients by offering education about risks of prolonged sitting or standing, support to change behavior, break and exercise snack ideas for moving more throughout the day, and programs to offset typical physical consequences of prolonged sitting.

“The human body was made to stand, walk, jog, run, climb, carry heavy objects, throughout the day, not to sit,” says Tamara Smith, NASM-CPT, CES, SFS, WLS, owner of Dreamtree Principle, in Long Beach, California, who has been working with corporate clients for over a decade.

Smith notes that a number of side effects may occur from sitting for the entire day, if nothing outside of work is done to counteract it. These may include any of the following:

- “tech neck,” or a protracted neck, in which the head and neck extend forward

- upper crossed syndrome, in which the major and minor pectoralis are short and tight; the upper trapezius and levator scapulae are strained and overactive; and shoulders are rounded, protracted or elevated

- weak abdominals

- tight hip flexors

- lumbar lordosis, or swayback

- weak glutes

Smith recommends that clients stretch tight muscles daily and do a simple strength routine two or three times per week to target typically weak muscles.

Sit Less—Move More

What research tells us and what makes good sense is that the human body is designed to move. Fitness pros are experts in how to move the body for physical and mental benefits. As such, fit pros have an opportunity to engage and motivate people on both how and why it’s important, not only to exercise, but also simply to move more every day. Even the latest edition of Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (HHS.gov 2018) highlights this emphasis on encouraging any amount of physical activity. Now, more than ever, with a sweeping epidemic of sedentary behavior, fitness professionals need to promote less sitting and more movement, up to and including moderate to vigorous exercise and muscle-conditioning activities. Millions of Americans need help with this message. We don’t have a moment to lose.

Sample Training Program A

Tamara Smith, NASM-CPT, CES, SFS, WLS, owner of Dreamtree Principle in Long Beach, California, recommends doing the following simple routine (twice or three times weekly) to strengthen typically weak muscles in office workers. Start with 1 set of 20 reps and work up to 2 or 3 sets of each exercise.

- frontal-plane tube walking to strengthen gluteus medius

- basic squats to strengthen gluteus maximus

- transversus abdominis activation, or the “draw-in” maneuver

- planks

- pelvic tilts lying supine, knees bent, feet flat on floor

- bridges to activate glutes and strengthen core

- quadruped arm raises, followed by opposite-arm/opposite-leg raises

- cobra: double arm followed by single arm

- “swimmers,” lying prone or on stability ball

- cervical spine retraction while prone on floor

Sample Training Program B

Michael Piercy, CSCS, PES, owner of The LAB Performance and Sports Science in Fairfield, New Jersey, offers solid advice for trainers who work with clients who frequently sit. “When [training] sedentary, deskbound clients it can be key to add some movement and energy to their workouts,” Piercy says.

“Envision how they might be in offices all day, performing routine tasks. Desk work can lead to postural issues such as rounded shoulders and compromised core integrity, so it’s a good idea to program exercises that target these areas.” Piercy also suggests that another important element is “to give the clients [moves] that are achievable yet engaging so that they feel accomplished and [obtain] a measure of excitement about continuing the program.”

Sample Deskbound Client Workout

Start with a short, dynamic warmup mixed with static stretches.

1A: jumping jack (3 x 30 seconds)

1B: plank (3 sets, 10 seconds per plank)

1C: body-weight squat (3 x 10 reps)

2A: high knees or jog in place (3 x 30 seconds)

2B: glute bridge (3 x 12–15 reps)

2C: dumbbell floor press (3 x 12–15 reps)

3A: plank jack (3 x 15 reps)

3B: curl-up (3 x 15 reps)

3C: TRX® low row (3 x 12–15 reps)

Go Deeper With the Updated CES Specialization

You may already know the basics of how to help clients with tech neck, lower-back discomfort and rounded shoulders, but there’s always room for refinement. The new, updated NASM Corrective Exercise Specialization, an already-proven program that addresses muscular dysfunction, will help you provide the best techniques available today.

“The updated version has been revised from the ground up with the fitness

professional as the target user,” says Rich Fahmy, MS, NASM-CPT, CES, PES,

content development and production manager. “Clinical applications such as

positional isometrics have been removed for the new CES, and the strategies

focus on the exercise professional’s environment and scope. We included more

real-world application and callouts on tech neck specifically.” There’s a

chapter on cervical-spine corrective strategies that focuses on forward-head

posture and the impact it has on overall function.

How specifically does CES help trainers deal with the kind of issues deskbound clients face? According to Fahmy, it gives trainers the ability to assess a client’s posture and preferred movement strategies (which are not always ideal) and create a program specific to the client’s needs. “Strategies provided—based on

individual assessment—follow the NASM corrective exercise continuum of reducing tension and improving extensibility in overactive tissues, improving strength in underactive tissues and encouraging ideal movement patterns with integrated dynamic movement.”

In the case of deskbound populations, CES enables trainers to reduce the

restrictions/overactivity and muscle underactivity in the hips, shoulders and

neck that are commonly associated with prolonged sitting. Fahmy provides the

following example:

A client who exhibits rounded shoulders will likely need to focus on foam rolling

and statically stretching muscles that contribute to the problem (such as the

latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major and pectoralis minor) and strengthening

muscles that pull the client into ideal posture (such as the mid and lower

trapezius and the rhomboids). Once each piece of the puzzle is optimized,

integrated movements such as pushing or pulling will be used to encourage the

muscles to “play nicely together,” referred to as intermuscular coordination.

Here are some additional highlights of the new version:

- It includes updated science.

- It features multiple experts in the field of corrective exercise, flexibility, human movement science, athletic training, physical therapy, performance coaching, assessment and recovery.

- There’s a new chapter on self-care and recovery, as well as one on applying corrective exercise techniques in the real world.

- It includes all-new application and lecture videos, along with updated techniques and strategies.

References

Akins,

J.D., et al. 2019. Inactivity induces resistance to the metabolic benefits following

acute exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126 (4), 1088–94.

Bureau of Labor

Statistics. 2019. News release: American time use survey—2018 results. Accessed

Sep. 11, 2019: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.nr0.htm.

Chaput, J-P., et al.

2015. Workplace standing time and the incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes:

A longitudinal study in adults. BMC

Public Health, 15 (111).

Diaz, K.M., et al.

2017. Patterns of sedentary behavior and mortality in U.S. middle-aged and

older adults: A national cohort study. Annals

of Internal Medicine, 167 (7), 465–75.

Diaz, K.M., et al.

2019. Potential effects on mortality of replacing sedentary time with short

sedentary bouts or physical activity: A national cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188

(3), 537–44.

Dupont, F., et al.

2019. Health and productivity at work: Which active workstation for which

benefits: A systematic review. Occupational

& Environmental Medicine, 76, 281–94.

Francois,

M.E., et al. 2014. “Exercise snacks” before meals: A novel strategy to improve

glycaemic control in individuals with insulin resistance. Diabetologia, 57 (7),

1437–45.

HHS.gov (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2018. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed Oct. 16, 2019: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/pdf/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf.

Jenkins, E.M., et al.

2019. Do stair climbing exercise “snacks” improve cardiorespiratory fitness? Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and

Metabolism, 44 (6), 681–84.

Klepeis, N.E., et al.

2001. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A resource for

assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal

of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 11 (3),

231–52.

Krause, N., et al.

2000. Standing at work and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Scandinavian Journal of Work and

Environmental Health, 26 (3), 227–36.

Ku, P.W., et al. 2018.

A cut-off of daily sedentary time and all-cause mortality in adults: A

meta-regression analysis involving more than 1

million participants. BMC Medicine,

16 (1), 74.

Lurati, A.R. 2017.

Health issues and injury risks associated with prolonged sitting and sedentary

lifestyles. Workplace Health

& Safety, 66 (6), 285–90.

Tudor-Locke, C., et al.

2014. Changing the way we work: Elevating energy expenditure with workstation

alternatives. International Journal

of Obesity, 38 (6), 755–65.

Ussery, E.N., Fulton,

J.E., & Galuska, D.A. 2018. Joint prevalence of sitting time and leisure-time

physical activity among US adults, 2015–2016. JAMA,

320 (19), 2036–38.

Yang,

L., et al. 2019. Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population,

2001–2016. JAMA, 1321 (16), 1587–97.