The madness is back again. A time of basketball fervor, crazy bracketology science and an array of wagers regarding who will make it to the dance and win it all. With many hopes and dreams riding on the shoulders of teams and individual players, sometimes it might just be one simple injury on your favorite team that can dash your entire pool strategy and tournament.

What follows might be a brief period of deflated enthusiasm, denial, and anger, before accepting that life must go on. But what about for the athlete who suffers that injury? How does he or she move on and cope? More importantly, how might this injury have been avoided in the first place?

Borrowing a famous quote from Benjamin Franklin who once said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” an integral part of any training program plan is the completion of a thorough needs assessment. Regardless of whether a coach is working with a college basketball star going to the ‘show’ or a fitness enthusiast wanting to replay the closing moments of a thrilling buzzer-beater, a key to preventing potential injuries involves the completion of a thorough needs assessment that addresses both the sport and the individual:

- Assessment of the sport or activity (observe, analyze, and ask top-level coaches and athletes if necessary):

- Utilized energy pathways (i.e., work bouts, intensity, recovery intervals).

- Movement patterns.

- Planes of motion.

- Injury analysis (examining prevalent injuries and causes associated with the sport or activity).

- Psychological needs (optimal arousal levels, tolerance for discomfort).

- Assessment of the individual(s):

- Current conditioning level, skills, and abilities v. amounts needed for success.

- Individual strength and weaknesses within the physical fitness parameters.

- Movement efficiency (appropriate levels of stability and mobility), form, and technique.

- Injury history.

- Psychological traits.

The information gathered through this assessment process provides vital information for comprehensive program design addressing multi-factorial needs. Although many coaches are well versed in corrective exercise (e.g., NASM’s evidence-based corrective exercise approach) and physiological programming, how robust are our programs with respect to addressing potential psycho-emotional events that may lead to an injury?

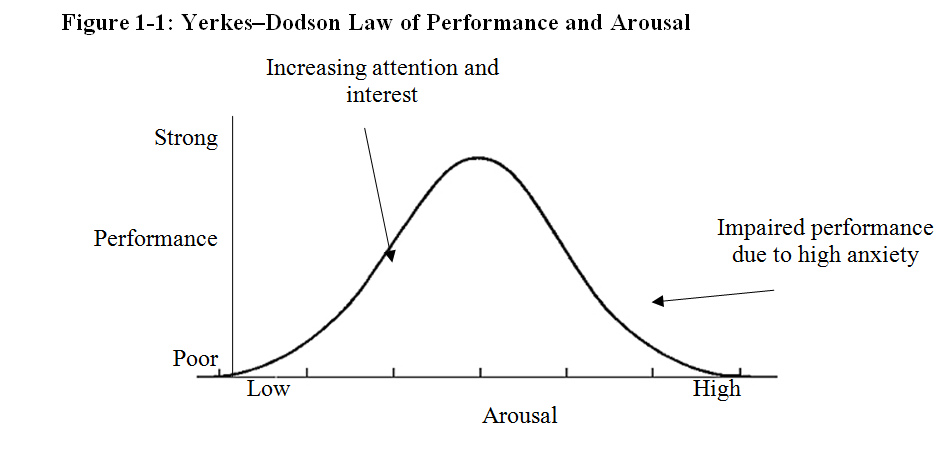

For example, physiological arousal is a trait many athletes thrive upon for motivation to play harder. Every player has a unique arousal level that optimizes their performance but what are the consequences of over-arousal? Typically we witness decreased performance, decreased attentional focus, and an increased potential for injury. A good coach is one who not only designs and develops a solid physiological program, but one who also examines the impact of cognitive and emotional states on performance. As illustrated in Figure 1-1, the Yerkes-Dodson curve demonstrates the relationship between performance and arousal (1).

Optimal performance requires a specific level of arousal, therefore a good coach is one who recognizes how over- or under arousal impacts motivation, concentration and anxiety levels of their players. They will determine the desirable level of arousal for each individual in order to promote maximal performance. Compare the level of arousal usually witnessed by a linebacker versus a quarterback right before kickoff in a football game– each needs to find their optimal level to perform at their best.

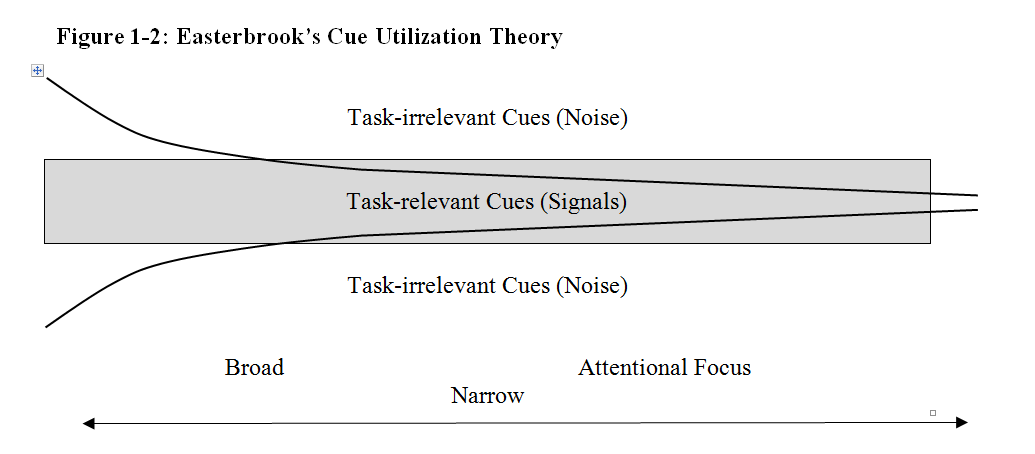

Easterbrook’s cue utilization theory aligns with this concept and explains how increased arousal tends to reduce the field of attentional focus by impacting the attention given to cues (stimuli) (2). This theory hypothesizes that at low levels of arousal, one’s attentional focus is very broad and the individual will process task-irrelevant and task-relevant cues simultaneously, which may disrupt performance (Figure 1-2).

By contrast, with high arousal levels, one’s field of attention becomes narrowed to the extent that the individual may actually gate out essential, task-relevant cues that may compromise performance, which may also increase the potential for injury (3). Anderson and Williams also developed a predictive model of athletic injury where they hypothesize that excessive levels of arousal narrows an individual’s attentional focus, which in turn may result in the failure to pick up vital cues within the environment that could potentially be injury causing.

The primary takeaway message here is one where we, as coaches, should appreciate how arousal can motivate all levels of basketball players, but also consider how excessive levels of arousal may decrease performance and increase the potential for injury, essentially undoing all we’ve strived so hard to attain. Although this article touched briefly upon arousal and performance, there are other psycho-emotional implications worthy of consideration in program design. Take the time to consider how these concepts might improve your training philosophy and results.

Reference:

- Yerkes, RM, and Dodson, JD. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 1908, 18:459 – 482.

- Easterbrook, JA. The effect of emotion on cue utilization and the organization of behavior. Psychological Review, 1959, 66:183 – 201.

- Anderson, MB and Williams, JM. A model of athletic injury: Prediction and prevention. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1988, 10:294 – 306.